Already an endangered species, the smallest community banks are further threatened by a growing regulatory burden.

A robust mergers-and-acquisitions market several years ago consolidated hundreds of the smallest banks, those with less than $200 million of assets. Then came the economic downturn, which made them the industry's most vulnerable to failure. But the rising cost of compliance is the biggest threat today to the smallest banks.

Even the healthiest of them say they face dizzying challenges.

"It seems like every time we get to a certain size I just think, 'Gosh, if we could get to the next level, we would eliminate this burden or that burden,' " said Kevin Yepsen, the president of the $100 million-asset Community State Bank in tiny Galva, Ill.

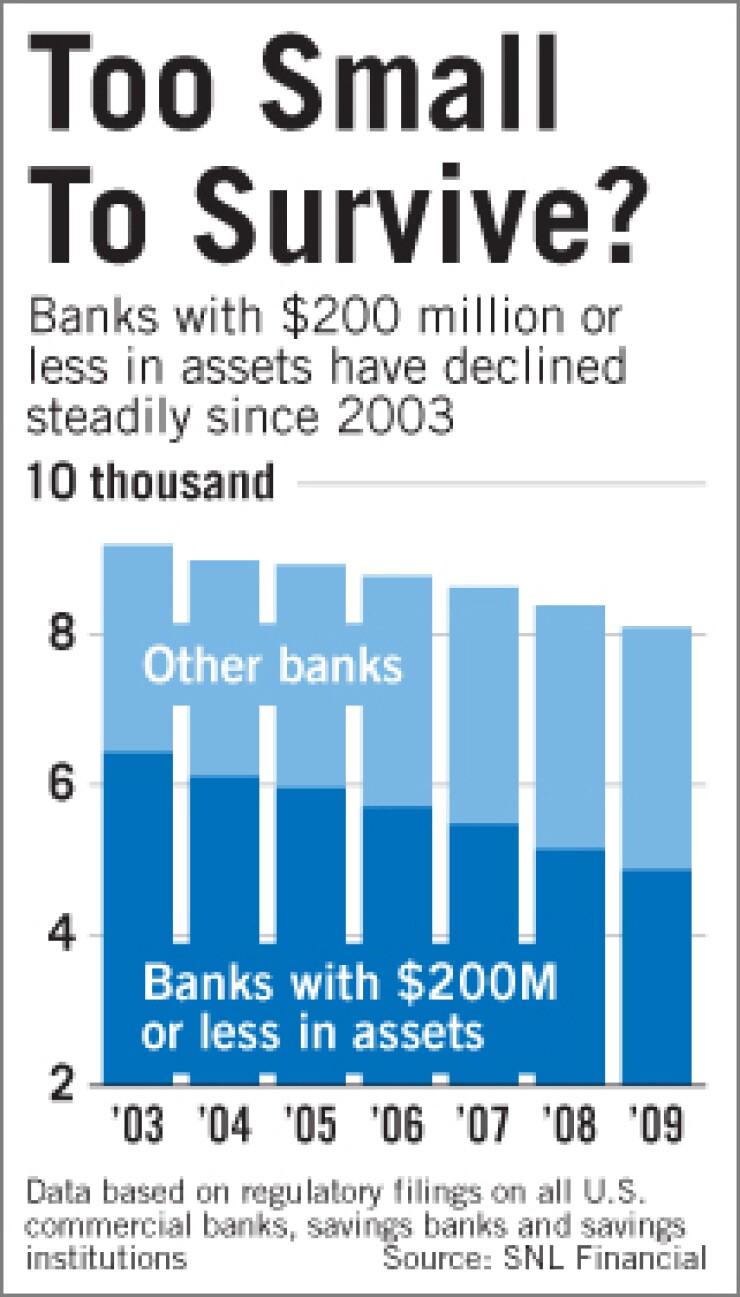

In 2000 more than 75% of the country's 9,907 banks and thrifts held less than $200 million of assets, according to data compiled by SNL Financial. By five years ago, this ratio had shrunk to 66.7%. Last year, it had declined to 60% of U.S. financial institutions, or 4,853 out of 8,086 banks and thrifts. These institutions own 3.3% of the country's total bank assets, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Many of the smallest institutions have been acquired — through traditional M&A or after their failure — and others grew out of the "tiny" asset class. And the FDIC has allowed only a handful of new banks, which tend to start off small, to open their doors since the start of the financial crisis.

"There's never been a formal moratorium, but if you look at the number of de novo insurance approvals, that number has dropped drastically since 2008," said Jeffrey Hare, a partner at DLA Piper in Washington.

In 2007, the FDIC approved 215 de novo applications, according to its 2008 annual report. Last year, it approved just 10.

Competition from larger banks and limited access to capital will make it difficult for the smallest banks to survive in the years ahead, analysts said. Yet compliance remains the biggest issue.

"I think the regulators are less likely today to let small banks off the hook with complying with all the regulations, and the costs are just becoming enormous to bear," said Rick Maroney, a managing director at Austin Associates in Toledo.

This directly affects small banks. In Galva, five of Community State Bank's 38 employees were out of the office Tuesday at seminars brushing up on the latest compliance issues, Yepsen said. The bank does not have a dedicated loan review or compliance officer, so the employees handle these issues with help from an outside accounting firm.

And Yepsen said the firm's regulatory costs have risen sharply. Deposit insurance, for example, is now 12 times what it was in 2007 while its assets have increased marginally in that period.

"We still have some banks in our area that are $10 million, $20 million, $25 million — I just wonder how they do it," said Yepsen, who started at Community State in 1990 when it had $12 million of assets.

Small banks in rural communities tend to be insulated from some of the economic stress facing tiny banks in larger markets. But even isolated banks say they face competition in the digital age.

Royal Bank in Elroy, Wis., with $224 million of assets, competes with online banks, credit unions, retail stores that offer credit cards, and local auto dealers that provide car loans. "Even though you might be the only office in town, you're still competing against everyone, all the time," said Richard Busch, the bank's president.

Steve Sant, the president of 1st National Community Bank, a $125 million-asset bank in East Liverpool, Ohio, said raising capital is tough for small banks, which lack access to capital markets. "I think that increases our cost to capital, which tends to make us a little bit less competitive," he said.

The company was able to raise $3 million in the first quarter of 2009 by selling 8% private preferred stock, which was more costly than a common stock offering would have been, Sant said.

Of course, plenty of the smallest banks remain strong, industry observers say. Those that succeed tend to serve niche markets, have solid core deposits, stay within their geographic markets and diversify their revenue streams, said Timothy Koch, a professor of finance at the University of South Carolina and president of the Graduate School of Banking at the University of Colorado.

But those without sufficient capital, ample core deposits or pristine assets are treading water, he said. "You're going to see many community banks do quite well, but you're going to see some who say: 'I'm ready to let somebody else run this shop,' " he said.

Small banks may also look to merge with peers.

"More smaller but commonly sized organizations will likely look to affiliate with each other in some regard as a way of combating these things that are hurdles to future profitability," said Philip Smith, president of Gerrish McCreary Smith of Memphis.

In a speech to Tennessee bankers this week, Julie Stackhouse, the senior vice president of banking supervision, credit and the center for online learning of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, said small banks should consider whether they have the scale to compete and to handle the coming regulatory burdens. Asked whether such banks should merge to achieve scale, she said, "Those that are strategic will begin to think that way."

That is not necessarily a bad thing, said Terry Keating, a managing director at Amherst Partners in Chicago. Other industrialized nations do not have nearly the number of banks that the United States does, he noted.

"It's great for the consumer, great for the businessman, but as an economic system, I'm not sure I think that's entirely healthy," he said. "And I expect we're going to see that shrinking."