-

An effort is gaining momentum to require banks that want municipal business to lend more in low-income neighborhoods. And it's not just mega-banks being targeted — smaller banks are seen as fairing worse in this type of lending.

June 5 -

Occupy Wall Street protesters and other pro-consumer groups are pushing leaders in some U.S. cities to shift municipal funds from big banks to small, local banks or credit unions. But they are finding it is hard to succeed.

April 10 -

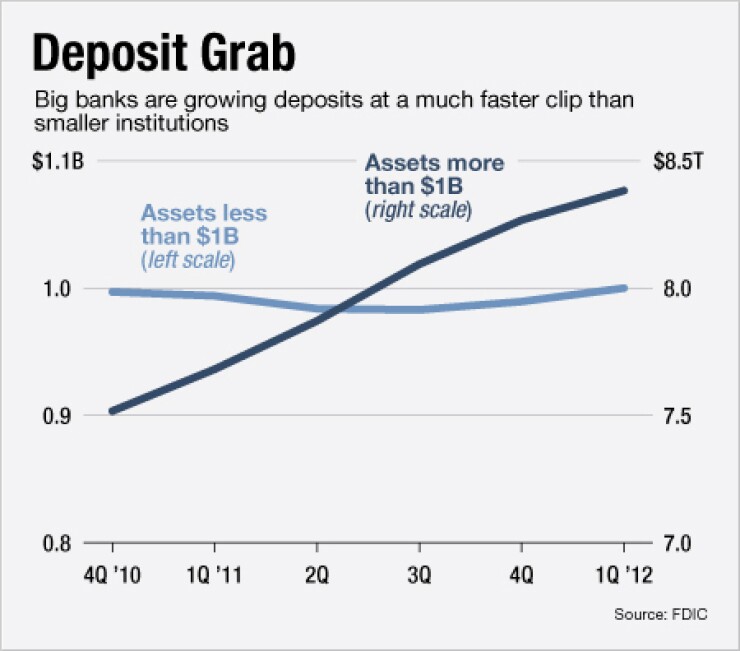

There's bad news for those who withdrew funds on Bank Transfer Day to punish the targets of their ire. Most banks don't really need their money at least not right now.

November 9

A number of state officials are trying to move deposits to community banks, though it is unclear if smaller institutions have the capacity or regulatory blessing needed to hold the funds.

Municipalities

Still, you can't blame the states for trying to help the little guys.

"A lot of times, community banks want a connection and to help their local governments and communities," says Seth Metcalf, the chief financial officer for the State Treasurer of Ohio

The office has launched STAR Plus, which pools investments from municipalities and redistributes them to banks as insured interest-bearing accounts. Qualified banks can participate, but Ohio State Treasurer Josh Mandel has been marketing the program to small banks based in the state.

"We can increase yields on behalf of taxpayer dollars, maintain security for schools and cities, and we could offer a new opportunity for community banks," says Mandel, a Republican who is running for U.S Senate.

"In a lot of ways, this program was specially made for us," says Rhett Huddle, the chairman and chief executive of Columbus First Bank, a $217 million-asset bank in Worthington, Ohio.

Ohio held its first webinar for the program June 8; there were roughly 130 participants. About $40 million has been committed since the program debuted on May 24.

Cities such as Pittsburgh and Los Angeles

Ohio has no loan requirements. The program has a higher yield, currently at 25 basis points, compared to a legacy program that also had collateral requirements.

The biggest risk with such efforts lies exactly where municipalities want to park their deposits: community banks. A deposit spike has left many small banks flush with liquidity, making it difficult for them to accept bulk sums of deposits when there are fewer ways to lend it out.

"We want core deposits and we want a relationship," says Joe Goyne, the chairman and president at Pegasus Bank in Dallas. "We have core deposits from our community. When checking accounts are increasing at 80% a year, your appetite for institutional funding is pretty meager."

Texas has a similar deposit program that requires a bank to match it with collateral.

Metcalf says some banks will not want more deposits, though the program's weekly liquidity lets municipalities and banks set their own timelines. "The banks offer a rate under this program that they would offer to anybody else," he says. "They can reject funding at any time. There's no mandatory participation."

Small banks are worried about how regulators will treat the deposits. Huddle says he plans to participate in Ohio's program, but he unsure if regulators will consider them core deposits or brokered deposits since a third-party custodian will distribute the funds. Regulators consider brokered deposits riskier because they are viewed as fleeting.

Regulators try to determine "how stable a deposit is and how sensitive it is," says Kurt Purdom, the director of bank and trust supervision at the Texas Department of Banking. "It could be considered potentially volatile" based on "how a bank received them and if you're paying an exceptionally high rate."

Small banks often are limited in capacity and technology to handle big municipal deposits.

Earlier this year, the city council in Austin, Texas, tried to move deposits out of Bank of America. After soliciting 112 bids, they chose JPMorgan Chase. None of the bids came from small banks or credit unions.

"We have to compete with major banks that have an unseemly amount of dollars in technology," says Don Padgett at Century Bank in Santa Fe, N.M. Municipalities want "more real time information and we have to be able to provide that."

Last month Century won a contract to manage New Mexico's insurance deposits for the Public Regulation Commission's Insurance Division. The fund, at more than $400 million, is almost as much as the bank's total asset size of $549 million. Century lost the annual contract for five straight years to bigger banks but had spent the time getting its technology and staff up to speed.

"It's a very large undertaking for a smaller trust operation but it will result in $450,000 to $500,000 in annual revenue for the bank," Padgett says.

New Mexico's Superintendent of Insurance John Franchini says federal regulators had actually stopped them from catering the bid process to small banks last year. "One thing we learned was that ... we couldn't have a law that sets a state priority and special favors," he says. "This year we were completely transparent and open and the irony is a state-domiciled bank won the bid."

Metcalf says the Treasurer's office has not directly communicated with bank regulators, though the program administrator has not received any objections from state or federal regulators.

"Having no objection is the best you're going to do," he says. "This is anti-bailout but not anti-Wall Street banks. Hopefully, this will help support a system that reduces the too big to fail."