WASHINGTON — Justices on the Supreme Court appeared split Tuesday on whether state bans on credit card surcharges are legal, with conservatives on the bench concerned about how the bans have been applied while liberals appeared skeptical of claims they violate retailer's free speech rights.

The case, Expressions Hair Design v. Schneiderman, centers on a New York state law that bars merchants from charging credit card users an additional fee while simultaneously permitting merchants to offer a discount to customers who pay in cash.

During oral arguments on Tuesday in front of the high court, plaintiffs argued that the law was unconstitutional since it restricted the free speech of retailers who wanted to charge a "credit card surcharge," which isn't allowed under the law, versus offering a "cash discount," which is allowed.

But the state — supported by the U.S. Department of Justice — argued that the law is about price transparency, not free speech. The law does not inhibit retailers from effectively charging more to recoup any costs associated with credit card transactions, nor does it prevent them from encouraging customers not to pay with credit card. It simply is meant to ensure that retailers do not lure in customers with a lower cash price, only to have the price increase — sometimes substantially — when the customer elects to pay with a credit card.

"Nothing in the statute prevents merchants from educating customers about credit card costs," said New York State Deputy Solicitor General Steven Wu. "That speech is arguably a better way to inform customers."

But Expressions Hair Design and four other businesses said the way that the law is applied — and the apparently vague criteria for what constitutes a violation and what does not — raises questions about how the law can be squarely interpreted as a price disclosure law with no free speech implications.

"This is a criminal speech restriction," said Deepak Gupta, an attorney representing the plaintiffs in the case, alluding to the fact that violation of the state law carries with it a penalty of up to a year in jail. "Typically a disclosure requirement doesn't leave you in the dark about what you have to say."

The liberal justices repeatedly questioned the basis of that argument, namely that a limitation on retailers' ability to describe a two-price system based on the customers' elected payment method as a "surcharge" is a violation of a constitutional right. Justice Elena Kagan noted that nothing in the law dictates what retailers can charge or how they arrive at that decision.

"I can imagine ways in which this is restricting free speech, but [the plaintiffs' argument] is not it," Kagan said, noting that the provision for two prices based on cash or credit makes the description of those prices somewhat secondary. "As long as that's true, you can describe it any which way you please."

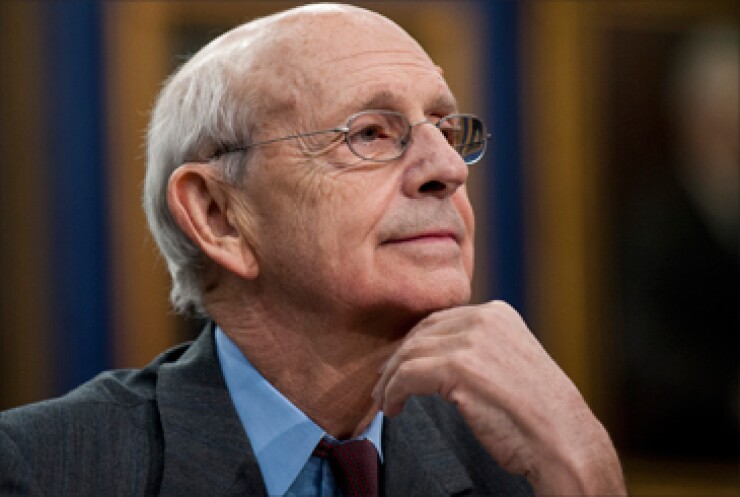

Justice Stephen Breyer was especially concerned that, because the law is somewhat ambiguous about where price setting ends and free speech begins, the court runs the risk of creating an arbitrary standard that could apply in any number of price-related functions of government.

"What we are doing here is taking all of these principles in First Amendment cases and … diving headlong into an area called 'price regulation,' " Breyer said. "If you want to know what's worrying me, that's it."

The court's conservative justices were more troubled with the state's application of the law. Justice Samuel Alito said that if the state law can be interpreted as requiring merchants to post the higher, credit card-based price instead of the lower cash-based price, that seems troublingly close to mandating that merchants say one thing and not another.

"If that is the correct interpretation of the statute, what New York State has done is to force the merchant to post a higher sticker price rather than the lower sticker price," Alito said. "Isn't that mandated speech? They are forcing the merchant to speak in a particular way."

Wu laid out a series of examples of what kinds of speech would be acceptable under the statute and which would not: posting two separate prices for cash and credit, for example, would not violate the rules, he said, while posting a price of $10 for a product with a $0.20 surcharge would. Wu said that logic was based on the duty for customers to view in total the highest possible price they might have to pay.

Chief Justice John Roberts appeared skeptical that such a rule was in service of a genuine consumer protection interest.

"Are you saying the American people are too dumb to figure out that $10 plus $0.20 is $10.20?" Roberts asked.

Alito suggested that the ambiguity in the statute as to what is permitted and what is not may require some additional information from the state courts — a hint that the bench may ask the state court for a "certification" as to what the statute means before ruling. Such a decision would be more likely if the justices are deadlocked 4-4.

Alito was also troubled by the scope of the law, which would apply to all sales in the state save for some transactions by state agencies. Would a particularly enterprising child's lemonade stand be found in violation of the law, he asked Wu, if it posted a sign offering lemonade for $1 but charged credit card users $1.05?

"The statute has no exemption for kids selling lemonade," Wu said. "I think prosecutorial discretion would apply there."