WASHINGTON — The pending return of roughly $68 billion of Troubled Asset Relief Program funds has raised several key questions, including whether and how the Treasury Department plans to redeploy the money and if banks unable to repay their government capital will begin to suffer in comparison.

The move makes it increasingly unlikely the Treasury will return to Congress to seek additional money. Once the 10 banks return their government capital, the Treasury will have roughly $270 billion left in the program.

But how the agency plans to spend that money remains a mystery. President Obama suggested Tuesday that some of it could be used to pay down the national debt, while others said it may help fund an expanded loan modification plan or program to purchase toxic assets. Ultimately, it may just be held in reserve as a buffer in case the economic situation worsens.

"It's nice to have that money there to fill any holes that develop in the system," said Mark Zandi, the chief economist and a co-founder of Moody's economy.com.

But the announcement also raised questions of whether the repayments would spark a backlash against banks that cannot return the funds, including Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America Corp.

"There are certain major banks not on the list who, if the regulators are clearly expressing some concerns about those institutions ... it would be my guess that they would not be quite as quick to let them repay and thereby cut whatever other strings they might have," said David Katz, a partner at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP.

Bart Narter, a senior vice president in the banking group at Celent, said that even though banks have had an easier time raising capital lately, investors may be more attracted to institutions that repay Tarp.

"Every investor knows that" banks are "exceptionally motivated to get rid of the Tarp money," he said. "The fact that" a bank "can't says that its capital structure is such that it still needs Tarp money."

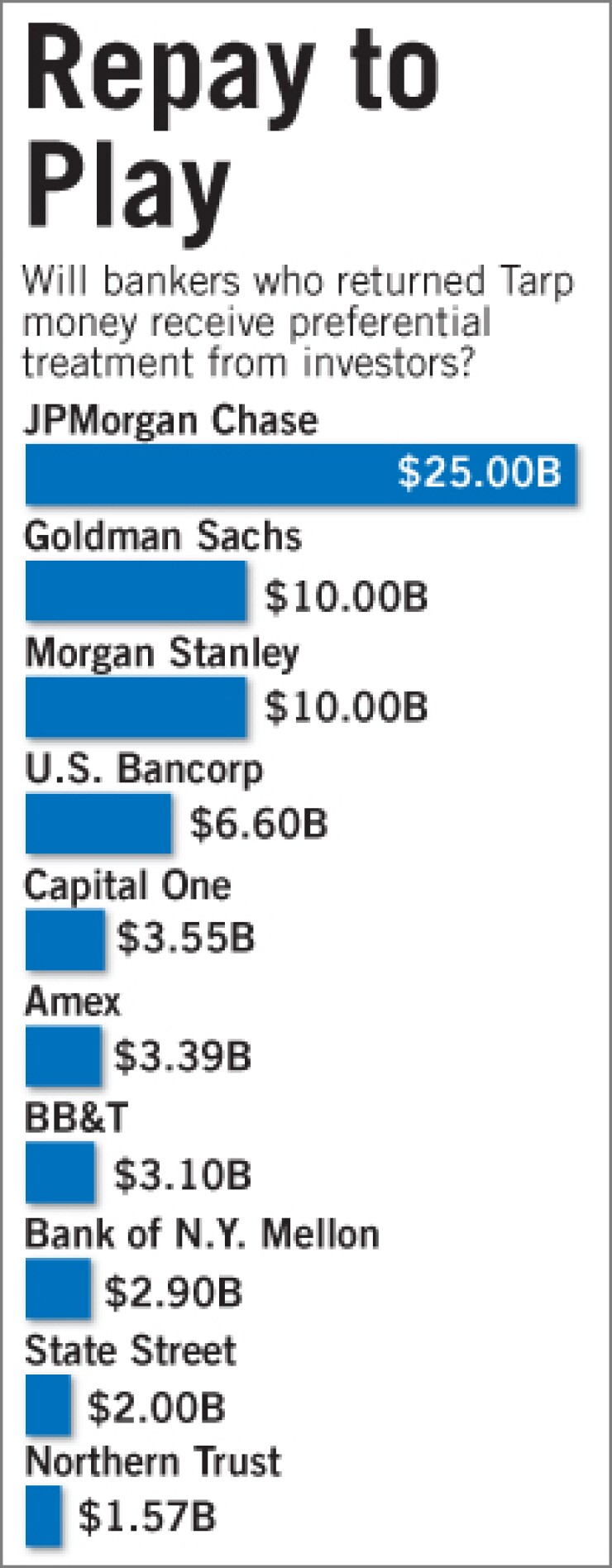

Among the $68 billion in repayments announced Tuesday, the largest by far was that of JPMorgan Chase & Co., which was cleared to repay $25 billion. Other large firms that said they would repay funds were: Northern Trust Corp., BB&T Corp., Morgan Stanley, State Street Corp., U.S. Bancorp, American Express Co., Capital One Financial Corp., Goldman Sachs, and Bank of New York Mellon Corp. The Treasury said those firms have already paid $1.8 billion in dividends. (Twelve smaller firms had earlier received approval to repay roughly $2 billion in government capital.)

President Obama indicated Tuesday that the returned funds will help offset the federal deficit, but he also signaled that the Treasury could recycle the money for future use.

"We're restoring funds to the Treasury where they'll be available to safeguard against continuing risks to financial stability," Obama said. "And as this money is returned, we'll see our national debt lessened by $68 billion — billions of dollars that this generation will not have to borrow, and future generations will not have to repay."

Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner has said that under the law, the repaid money will go into the agency's "general fund." However, despite objections from some lawmakers, the administration has also said the law that authorized the bailout allows the Treasury to respend funds for its financial rescue program as long as the total balance committed does not exceed $700 billion.

At a hearing Tuesday, Geithner said the repayments give the government more "flexibility."

"We do not expect at this time to come back to Congress to ask for authority to use those resources," he said. But he added later, "I think to be realistic, there is a lot of risk ahead for us, and we need to be careful to remind people that flexibility there is important."

Geithner hinted that the Treasury may soon have even more money. Under the terms of Tarp, the agency still holds warrants for the 10 banking companies that are allowed to repay, and continues to try to negotiate a fair market price for them.

"Some of the estimates are in the several-billion-dollar" range collectively "for those initial banks that are repaying," Geithner said.

The extra money allows the Treasury to spend on other areas without worrying about having to ask Congress for more money, which lawmakers would be unlikely to authorize.

For instance, the agency could choose to allot more than the $75 billion to $100 billion in Tarp capital it had initially envisioned for its Public-Private Investment Program, a plan to help remove bad assets from banks' balance sheets. The program has sputtered since its unveiling, with regulators shelving a component of the plan — spearheaded by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. — to clean up whole loans, and the Treasury has yet to launch a PPIP facility for asset-backed securities.

"It's very important for Treasury and the FDIC to continue to work on something like the PPIP, which seems to be losing momentum," Zandi said.

He added that a plan to boost mortgage modifications — using $50 billion of Tarp funds — has slowed.

"Their current modification plan appears increasingly inadequate," Zandi said. "If they could put more resources to that problem, it would be very effective."