A New York state program to bring banking services to neglected areas is a microcosm of the industry's problems in courting underbanked consumers.

Since 1999 the New York State Banking Department has offered tax breaks, below-market-rate municipal deposits and other incentives to banks that set up branches in underserved neighborhoods. So far, 38 branches in the state, including 25 in New York City, have qualified for Banking Development District, or BDD, status. Participants have ranged from national companies like Citigroup Inc. and Capital One Financial Corp. to small, local institutions.

But despite bank interest in the program — and its perks — critics say the participants have not demonstrated they can meet the needs of underbanked people. Reported shortcomings range from practical things like branch hours and language skills to more fundamental matters like products and services offered and bank disclosures.

These issues are likely to take center stage this week when the department presents recommendations to the state banking board about how to expand the program.

Even some bankers involved in the program acknowledge that they have an image problem in the underbanked communities.

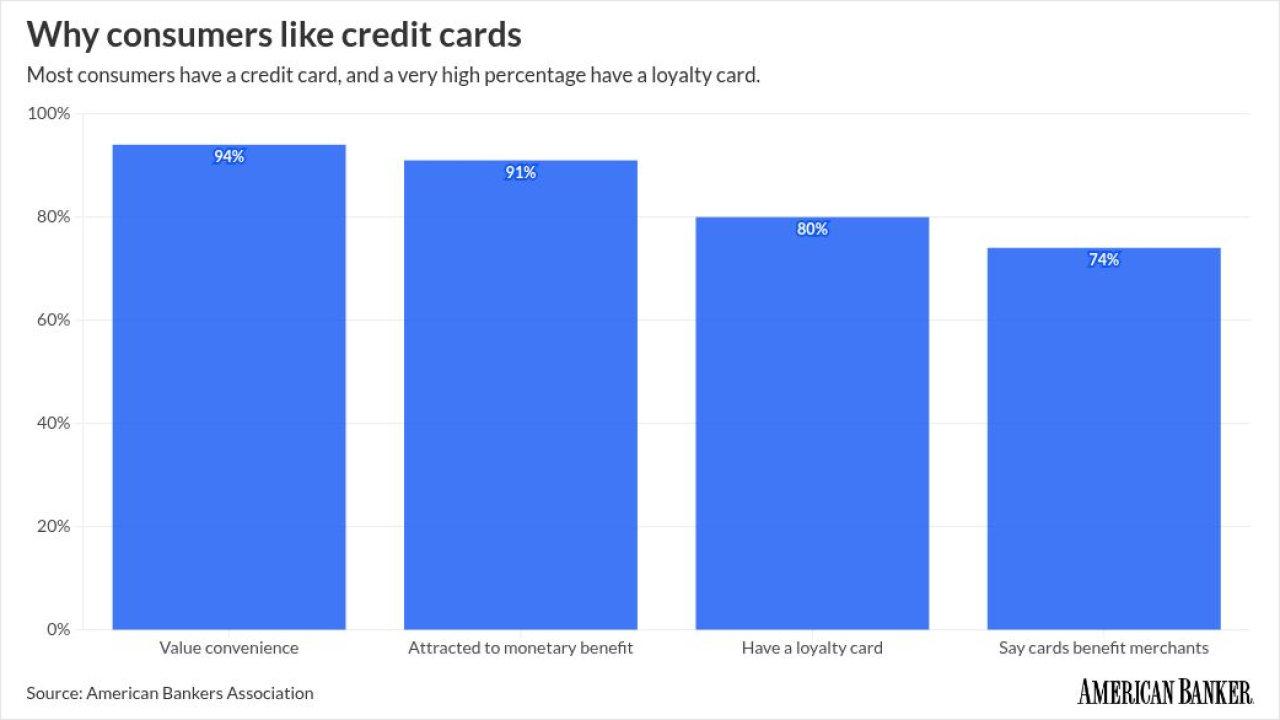

"A very large reason why individuals choose not to bank is due to this misunderstanding of what banks have to offer," said Erik Schumar, a vice president and the community development relationship manager at Amalgamated Bank, which has earned BDD status for four of its 14 New York branches.

"There's a pervasive thought and idea that banks have a lot of fees, require minimum balances" and that customers are "going to get stung with finance charges here and there."

In preparing its recommendations to the board, the department got input from a variety of groups at public hearings this spring — including credit unions, community groups and alternative financial services providers.

"There are ways to meet the needs of unbanked and underbanked people … other than banks," Jason Carballo, the president of the check-cashing trade group Financial Service Centers of New York Inc., said in an interview. "There is a mismatch between the bank products that are being offered and the products that people most need, such as check cashing, money transfer and electronic bill payment."

He and others also pointed out that many banks do not offer the extended hours or multilingual employees that are standard at check-cashers, remittance providers and other alternative financial services outlets.

Richard Neiman, the state banking superintendent, acknowledged that a gap persists between the products and services offered by traditional banks and those most used by underbanked people.

"What drives people's behavior is not simply the extent to which they have a bank branch open to them. You have to have products that will meet the needs of the population but also address the reasons that they're not dealing with the branch," he said in an interview.

For example, "when you go into a check-casher, the fees are readily known and posted, whereas in dealing with banks there may be a more complicated process of fees, regarding returned-check fees and bounced-check fees and interest rates, that may not be as easily understood by the individuals," he said. "So I think there needs to be a much greater focus on not only the establishment of a branch but [also] how that branch should be operating and changing behavior."

For now the banking department does not offer additional incentives to encourage such behavioral changes. Some argue that the time has come for such incentives.

"The next generation of the BDD program should focus on what happens inside the bank branches," and it should prod banks "to offer and sell the right mix of products and services — including basic bank accounts and clear, transparent options for overdraft protection," said Jonathan Mintz, the commissioner of the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, in testimony prepared for an April hearing. "Banks benefiting from BDD status should also commit to comprehensive reporting on how earnestly they've marketed and how successfully they've sold such products."

Schumar said Amalgamated has 3,000 customers at three of its development-district branches (the fourth was opened on Monday) and 50,000 in the city overall. "As is true for most newer branches," he said, deposits in those three "are all trending upward."

None of the other banks contacted for this article would disclose figures on deposits or customers at their development-district branches.

Mintz also said credit unions should be allowed to participate in the program, something the banking lobby opposes. (Only banks and thrifts are eligible for the program's benefits.)

Neiman said the state's program "certainly should be expanded and encouraged where appropriate," but he would not discuss specific recommendations ahead of this week's meeting except to say he would like to encourage participation outside New York City.

Some of the institutions participating in the program said they have made their own efforts to cultivate interest among people who may prefer alternative providers.

Capital One, which in December opened its third development-district branch, in Brooklyn, has a multilingual staff at its East Harlem office and conducts financial education seminars in English, Spanish and Chinese at its branches, according to spokeswoman Diana Don. It has also started a rent-collection program with the New York City Housing Association, which lets public housing residents pay their rent in cash at Capital One's BDD branches. "Each month since the launch, the number of transactions has increased. Each month the BDD branches process over a thousand rent payments," she said.

Schumar said that Amalgamated has extended its hours at some sites and has staffed one of its development-district branches, in Long Island City, with managers who are fluent in Spanish.

The New York State Bankers Association has proposed extending the length of the deposit subsidy beyond two years and allowing an institution that buys an existing development-district branch to receive its benefits.

But community groups said the program should require more from banks — including different product offerings and reported results. "You can provide the education, but if the services aren't there, the education is useless. There's a real sort of gap between the rhetoric of financial education and the availability of services in many of these communities," said Deyanira Del Rio, the associate director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project.

To groups like hers, she said, "it's unclear … what the tangible results have been of providing these very significant benefits to banks. There's no real long-term data to see what's changed over time and see how communities have actually benefited."