It's going to get worse before it gets better for the industry's oil lenders.

More than a year after oil prices began to plunge, long-feared problems with credit quality have begun to surface. Energy lenders have boosted their reserves, as they prepare for losses in their oil portfolio.

But if you want to get a sense of the long road ahead for energy lenders, take a look at a different figure: credit lines.

-

Comerica in Dallas is warning that its loan-loss provision this quarter will be larger than previously estimated because of falling oil prices.

February 29 -

Kelly King, BB&T's CEO, said his company is keen on eventually buying banks between Alabama and Texas, though his team would need to have frank discussions with any targets before pursuing a deal.

February 17 -

While the energy sector and regions that rely heavily on oil and gas production have been hit hard by the glut in the global oil supply and the closure of drilling rigs across the country, the probability of widespread bank failures as a result appears to be remote.

February 12 - Alabama

Standard & Poor's Ratings Services is warning banks with high levels of exposure to the energy industry to think twice before ramping up their lending in other sectors.

February 10

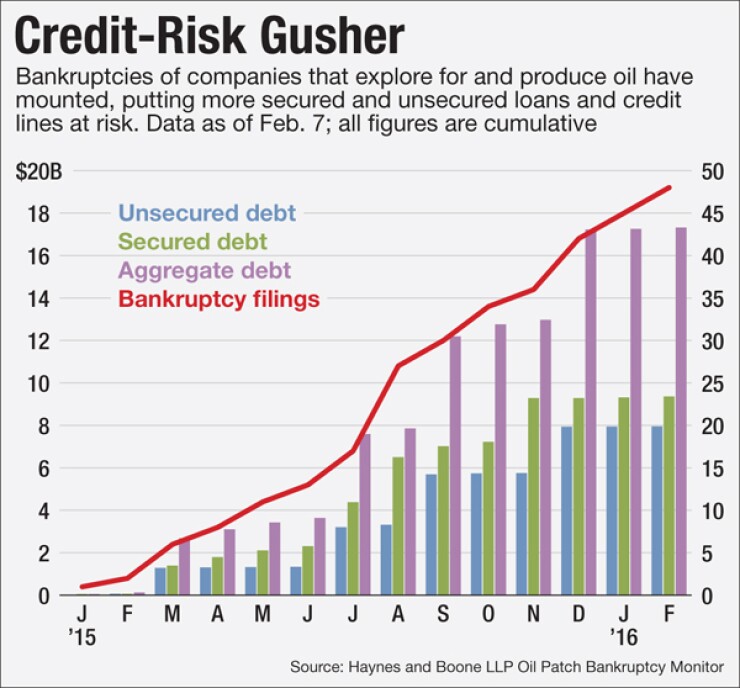

Cash-strapped oil companies have begun drawing down their revolving lines of credit, according to industry analysts. And that could be a sign that a wave of energy-related bankruptcies is on the horizon.

"There will be more bankruptcies," said Robin Russell, an attorney with Andrews Kurth in Houston, who specializes in bankruptcy law. "It will not be marginal."

Distressed companies typically rely on credit lines in a pinch. It's often a last-ditch option for liquidity, helping companies stay afloat and make payroll as they wait for the market to turn around.

But, with oil hovering around $30 per barrel, more companies have filed for or are skidding toward bankruptcy — and they are drawing down credit with the goal of stockpiling extra cash, experts said. Reorganizing under Chapter 11 can be expensive, and having liquidity on hand can give a company a leg up in the process.

Oil companies "are trying to fund the bankruptcy," Russell said.

Draw-downs are typically a signal for banks that a legal filing is imminent, according to John Thieroff, an analyst with Moody's.

For instance, Ultra Petroleum — an exploration and production company in Houston — said in a securities

The looming wave of bankruptcies come as oil lenders — such as

Several banks have also recently disclosed details about unfunded commitments to the energy sector, which includes the undrawn portions of companies' credit lines.

JPMorgan Chase said last week it has $44 billion in total commitments to oil and gas companies, but only a portion of that exposure — about $14 billion — has been funded.

Chief Executive Jamie Dimon told investors that he doesn't expect companies to significantly draw down their credit lines, noting that most of the company's borrowers are investment grade.

"They are not going to pull it down," Dimon said. "They don't need it."

In a recent presentation,

Smaller banks have made similar disclosures. In a

"As energy clients evaluate their cash flow needs, it is possible that outstanding loans could increase as clients draw against their unfunded commitments," the Atlanta-based company said in the filing.

The recent headaches over oil loans illustrate how many banks initially underestimated the severity and duration of the energy cycle.

The recent crash is unlike the regular, cyclical dips that cause headaches in the oil market, experts said. A glut of supply has pushed down prices — and made the market unlikely to rebound in the near future.

"Banks have been through a lot of cycles," Thieroff said. "There was a lot of patience" at first that the market would rebound.

Perhaps they showed too much patience. The recent boosts to loan-loss reserves occurred more than a year after prices began to fall.

But there are a number of factors that prevented banks from acting earlier, and reserving for losses when the crash began to unfold.

Across the industry, energy borrowers only began to show signs of significant distress within the last few months, analysts said.

That's because oil companies typically rely on hedges to protect cash flows against swings in the price of oil. Over the past few months, those contracts — which typically last between two and four years — have begun to expire.

As a result, many companies have only recently begun to feel the constraints from having oil at $30 per barrel for such a prolonged period, analysts said.

"As those hedges roll off, the cash flow is going to be impacted," said Chris Mutascio, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Hedging activity came to a standstill late last year — and will likely remain low as the market continues to fall, according to Thieroff.

It also simply takes time for corporate borrowers to show signs of distress.

Several major oil producers have announced cutbacks in the past few months. As those take effect, servicing companies will face renewed pressure, according to industry experts.

"It has a snowball effect," said Russell, the Houston-based bankruptcy attorney.

Additionally, banks are constrained by the rules and incentives that govern the provisioning process.

Banks have some leeway in creating their own model to account for losses, analysts said. But reserving too much can expose them to charges of earnings manipulation — while reserving too little can leave banks flat footed when problem loans arise.

It's "as much an art as it is a science," said Jeff Harte, an analyst with Sandler O'Neill.

As banks face the prospect of a rise in bankruptcies, they often have an incentive to allow companies to draw down their credit lines.

The lines of credit are typically secured, giving banks an incentive protect their collateral — even if it means giving cash to a failing company, analysts said.

"It's a real Hobson's choice," said Steve Sather, a bankruptcy attorney at Barron & Newburger, noting that those decisions are made on a case-by-case basis.

"What I would expect a smart bank to say is, 'Hey, we know you're heading toward bankruptcy. We will give you a little bit of cash to keep you afloat,' " Sather said.

Having extra cash on hand can boost an oil company's chance of avoiding liquidation and reorganizing, instead, under Chapter 11, according to Sather. The funds can also help companies avoid having to obtain debtor-in-possession financing — a restrictive agreement, typically made with a company's primary lender, that governs the restructuring process.

In the coming year, the pressures facing companies throughout the oil industry are expected to intensify.

With prices hovering at historic lows, many borrowers are running out of options to stay in business.

Moreover, semiannual redeterminations — in which banks reassess the borrowing capacity of certain commercial borrowers — are scheduled to begin next month. Banks are expected to cut back on credit for companies in the oil industry.

Moody's estimates that banks will cut credit lines by as much as 20%, Thieroff said. Such haircuts would lessen lenders' credit exposure in the short run, but the cuts will add an additional layer of stress for cash-strapped borrowers.

Banks, meanwhile, are girding for a long year of legal fillings and liquidations.

"We have only begun to see the range of bankruptcies in oil and gas," Doug Petno, JPMorgan's head of commercial banking, said at the company's annual investor day last week.