Concern that deposit pricing competition will crimp profits has taken a back seat recently in an industry reeling under widespread fallout from the mortgage market mess, but it hasn't entirely gone away.

The Federal Reserve has cut the federal funds rate twice in recent months, but deposit pricing has not followed suit. Players like Countrywide Financial Corp. and E-Trade Financial Corp. continue to be aggressive in their pursuit of deposits, and several larger banks are maintaining high rates for certificates of deposit and money market accounts. Meanwhile, smaller banking companies, where lending margins are a bigger part of the profit equation, find themselves having to make a difficult choice on whether to compete for deposits to fund loans.

In the near term, it seems inevitable that deposit competition will mean the already-intense pressure on net interest margins may get even more so as interest on variable-rate loans tracks the prime rate lower.

Richard Barham, the chief executive of Market Rates Insight Inc. in San Rafael, Calif., said that, though CD rates are starting to inch down, they are not falling at a pace corresponding with the Fed's rate cuts or with loan pricing. Money market rates remain high, he said, and "banks absolutely need to attract deposits any way they can."

"The competitive environment has been fairly severe, and a number of the institutions … are suggesting that the full benefit [of lower interest rates] might not be witnessed because of that," said Frank Barkocy, the director of research at Mendon Capital Advisors Corp. in New York.

"I think we're probably looking ahead into the middle part of 2008 before you start to see more of the benefits" of lower interest rates and their ability to improve profitability, he said in an interview this week.

Countrywide, a Calabasas, Calif., mortgage lender, and E-Trade, a New York online brokerage that has a bank unit, are among those who have looked to the Internet deposit-generation model as a way to secure funding after being burned in the mortgage meltdown and consequent liquidity squeeze.

In October, Angelo Mozilo, the chairman and chief executive of the $209.2 billion-asset Countrywide, described deposits as the "more reliable funding for the bank" and said the company would "try to stretch the deposits out." It has said that its low-cost operating model, in which infrastructure takes just 27 basis points of the deposit portfolio, allows it to offer higher-than-normal rates.

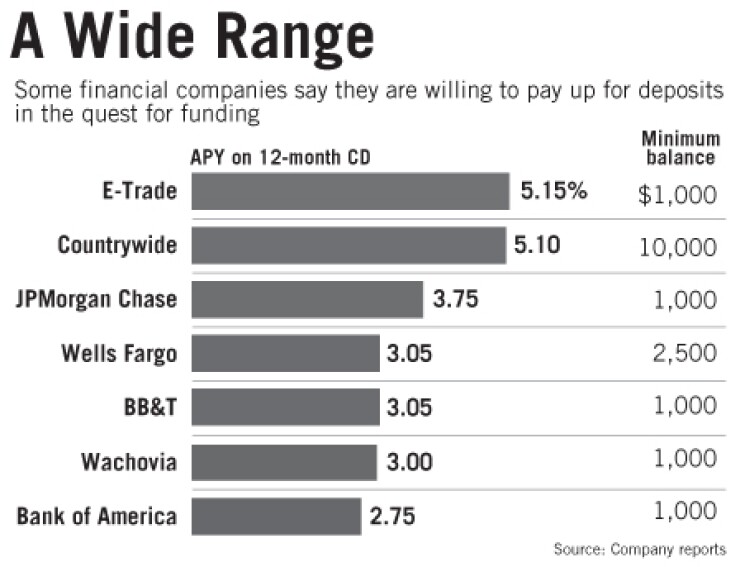

The company is marketing a 5.1% rate on a one-year CD, and the $64.2 billion-asset E-Trade is promoting a rate of 5.15%, according to their Web sites.

High deposit pricing is not reserved for nontraditional financial companies. Though its advertised one-year CD rate, at 2.75%, is little more than half that of E-Trade's, Bank of America Corp., the nation's largest retail bank and the holder of 14% of U.S. retail deposits, has shown it is willing to pay for deposits.

Joe Price, the chief financial officer of the $1.6 trillion-asset Charlotte company, explained during a Nov. 13 conference in New York why B of A got more aggressive. "Not only are the deposits the raw material for us to invest in quality loans, but they represent the opportunity to earn significant fee income such as debit card transaction fees," he said.

The goal, he added, "is to grow deposits at or somewhat above market growth rates. We have had slower growth as we perhaps overbalanced profitability versus market share, but today we're taking actions to grow deposits faster, and we are starting to see the volume needle move as a result."

B of A saw the average rate on interest-bearing deposits rise 15 basis points during the third quarter, as the average level of such deposits grew 1.5%. It is not alone; seven of the 10 largest U.S. banking companies that disclose the average rates on their interest-bearing deposits increased rates in the third quarter, compared to a quarter earlier, according to regulatory filings.

The $1.5 trillion-asset JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York saw its average fall slightly, and Wachovia Corp. in Charlotte and Regions Financial Corp. in Birmingham, Ala., reported no change. A JPMorgan Chase spokesman said Tuesday that it had benefited mostly from "good flows" in its wholesale business, such as treasury and security services and holding deposits for commercial banks, which he said was a direct result of the market disruption rather than its retail business.

More often, bankers are pointing a finger at their competitors for keeping rates high.

John A. Allison, the chairman and chief executive at the $130.8 billion-asset BB&T Corp. in Winston-Salem, N.C., said early last month at a conference in Boston that, though community banks had "calmed down some" in terms of pricing, Wachovia appeared more willing lately to keep its rates "a good bit higher," creating a challenge for other banks.

A Wachovia spokeswoman said she would not comment specifically on the company's deposit rates, though she said the company remains "focused on acquiring and growing checking accounts while actively managing our overall deposit pricing to maximize profitability, growth, and liquidity based on customer and company needs."

John G. Stumpf, the chief executive of Wells Fargo & Co., said during a Nov. 15 conference in New York that the $548.7 billion-asset San Francisco company had decided against raising its rates in California, though "some of our competitors" did. "Sustaining deposit growth is going to be challenging in the current economic environment," he added.

Mark Jacobsen, the president and chief operating officer of the Promontory Interfinancial Network LLC in Arlington, Va., said that, dating back to August but excluding October, volume has been good for the CD orders it processes for the more than 1,800 banks in its portfolio. "When the Fed changes rates, everyone waits," he said in explaining the October slump. "It looks like it will be a very, very strong December, but again we're dealing with more-sophisticated investors."

Mark Fitzgibbon, the director of research at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP, said Tuesday that not everyone is willing to compete with the large financial institutions on price and that an increasing number of banks, particularly smaller ones that get inordinately pressured by shrinking margins, are deciding to let CDs run off, replacing them with wholesale borrowings.

Donna M. Coughey, the president and chief executive of Willow Financial Bancorp Inc., said in an interview last month that the $1.5 billion-asset King of Prussia, Pa., company began deemphasizing high CD rates by limiting the best rates to those who had a relationship with the bank. "We're not allowing it to go beyond that," she said. BB&T's Mr. Allison said that his company is also trying to show more restraint, in particular by turning down commercial cash management accounts. Mr. Allison predicted that margins at his company should stabilize and show "some little bit of improvement next year."

Loan portfolios are growing at a slower rate at many banks, which is easing their need for deposits.

Lester Johnson, the president and chief executive at Columbo Bancshares Inc. in Rockville, Md., said his company began dialing back on CD rates as it monitored what is expected to be reduced loan demand in step with a lower prime rate. "Like most banks, we watch our loan demand, so with $33 million [in liquidity] we can fund our loans over the next six months to year without paying for expensive money," he said in November.

"The loan business isn't as vibrant as it has been in the past," Pierce Stone, the chairman and chief executive of Virginia Community Bankshares Inc. in Louisa, Va., said in an interview. "It's just a cycle. We're not putting out as much in loans, so we don't need that much in deposits."