WASHINGTON — Democratic presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton has made reining in the shadow banking system a focal point of her campaign platform, but there are fears that doing so could come with a high price tag for the U.S. economy.

While her rival, Sen. Bernie Sanders, D-Vt., has focused on big banks, Clinton has argued that shadow banking risks found in firms like hedge funds and private equity firms were responsible for the financial crisis. She has proposed steps such as giving the Financial Stability Oversight Council more power to target shadow banking activities, enhancing oversight of broker-dealers and improving disclosures.

Industry observers give Clinton credit for focusing on a critical issue, but they worry that more regulation could raise costs without making the system safer.

-

If the general election comes down to Hillary Clinton against Donald Trump, many community bankers are uncertain whom they will back. They fear Clinton will continue the regulatory crackdown against the industry, but are unsure what plans Trump would put in motion.

March 29 -

Hillary Clinton said she would consult with Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., on any choice for Treasury secretary.

March 10 -

House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling signaled an aggressive assault on the Dodd-Frank Act on Tuesday, outlining a bill that would allow banks to be released from some of the 2010 reform law's regulations and Basel III requirements if they hold sufficient capital.

March 15 -

In almost any other election cycle, bankers would be celebrating the fact that a Republican candidate has emerged so far in front of the pack and would quickly fall in line behind him. But this has been anything but a normal election cycle, and there are a whole host of reasons that bankers will be at least as reluctant to embrace the outspoken businessman Donald Trump as the Republican establishment has been.

March 1

"The elements of the Clinton proposal that specifically address 'shadow banking' seem to be relatively thoughtful, inasmuch as they focus largely on market activities, rather market participants as such, and on information gathering and related transparency measures," said William Shirley, of counsel at Sidley Austin. "But whether they would be sensible in practice would depend on details of implementation that are not described in the proposal."

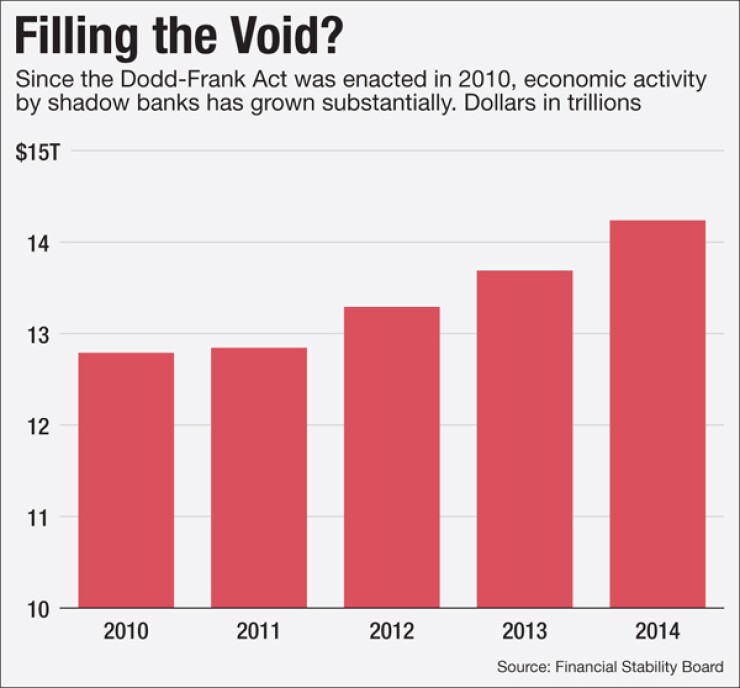

While Clinton and others fear that the riskiness of the shadow banking system — a nebulous term that encompasses many different industries — is growing, others contend that more regulation isn't the answer. Critics point to the Dodd-Frank Act, which they argue has added more complexity to the system but hasn't necessarily made it safer.

"We have tried to regulate things away, and the more complex our regulations are, the more complex the risks that we take are and the less we know," said Diane Swonk, founder of DS Economics.

A Government Accountability Office report released late last month highlighted the issue, noting that financial regulation could be simplified and suffers from regulatory overlap, while also saying that there is a gap in regulation that could lead to a buildup of risk.

The report keyed in on the powers of the FSOC, which is made up of nine regulatory agencies and chaired by the Treasury secretary. The council has the authority to designate a specific entity as systemically important, subjecting the firm to prudential regulation from the Federal Reserve Board, but it cannot compel its member agencies to take action against a specific activity.

That is a significant shortcoming, industry observers said, because naming individual companies is a tedious process at best. At worst, it's an ineffective one. The FSOC suffered a surprising and significant defeat in court last week when a federal court overturned its designation of MetLife as a systemically important nonbank.

Additionally, in terms of dealing with shadow banking activities, it is doubtful that designation of individual firms will adequately address the issue.

"You could designate one or another company, but you have done very little to deal with shadow banking risk, because there will always be another company doing the same thing and that has become more widespread," said Karen Shaw Petrou, managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics.

Part of Clinton's plan calls for giving the FSOC more authority. Her website says the U.S. should strengthen "the tools and authorities of the FSOC to tackle risks in the shadow banking system—wherever those activities may migrate or emerge."

Justin Schardin, acting director of Bipartisan Policy Center's Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative, said giving the FSOC more power to target specific activities could be significant.

"Systemic threats don't usually come so much from individual firms, but from risky activities and products that are present at a range of firms at the same time. FSOC doesn't have much authority to get at those," Schardin said.

But giving the FSOC more authority would also be politically challenging.

"You are either faced with strengthening FSOC and making it a much more coherent body than it is right now, which would take new law, or strengthening the nonbank prudential regulators so they would have more safety and soundness powers than they do now," Petrou said. "Neither of them would be easy sells."

Whether that authority is needed is debatable. Lawrence Goodman, president of the nonpartisan Center for Financial Stability think tank, said the "shadow banking system sounds like it is a nefarious place, but the reality is it is good old-fashioned market finance."

He added that data the group studies suggests that the economy is being bogged down by Dodd-Frank regulations.

"Since the crisis there has been a wave of regulation that in many ways has helped create a stronger banking system, but in many instances it has perhaps gone too far. Now is an outstanding time to stop and take stock," Goodman said.

Francis Creighton, executive vice president of government affairs at the Financial Services Roundtable, whose members include some of the largest banks, said that by focusing on activities rather than firms, Clinton's plan makes sense.

"Clinton's proposals really get to where are some of the gaps and how do we fill them in," Creighton said. "What we all want here is as close to a level playing field as is possible."

But he feared giving the FSOC too much power.

"We'd be very uncomfortable with idea of a political agency like the Treasury in effect being able to dictate to independent regulators what they can and cannot do," Creighton said.

But Oliver Ireland, a partner at Morrison & Foerster, argued that hedge funds and private equity firms are inherently risky — and should remain so.

"Somebody has got to take those risks, and if we stamp out taking out those risks the economy is not only going to stagnate in terms of growth, but you are going to choke off innovation," he said.