A vital cog of the United States’ financial system is at risk. For 89 years, the Federal Home Loan Bank System has been a reliable source of liquidity for most of the nation’s banks, credit unions and insurance companies. Without meaningful change, this remarkable public-private partnership is nearing the end of its relevance.

Created in 1932 during the waning days of the Hoover administration, this intricate structure of 11 — 12 at the time — banks scattered across the U.S. has been a bulwark of our financial system. Member-owned but federally supported, these 11 banks have provided backup liquidity to their members through secured advances. The system is able to fund itself through debt obligations it issues that carry reduced risk premiums due to the implied guarantee of the federal government.

The Home Loan banks that make up the system are cooperatively owned by the financial institutions in their districts. This is in stark contrast with their distant government-sponsored-enterprise cousins, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which were owned by profit seeking shareholders and are now in conservatorship. Each Federal Home Loan bank devotes a significant portion of its net income to affordable housing and to economic development in its district.

Through the Great Depression, numerous recessions, the Y2K scare, the savings and loan debacle, and other stresses in the financial markets, the system has been a stable source of funding for financial intermediaries. Long before the Federal Reserve rolled out its “urgent and exigent” instruments in the 2008 financial crisis, the system offered an oasis of funding when few others were in sight.

Now, this beacon of the financial system is itself at risk — not from any missteps of its own but rather from the pandemic-driven actions of the same federal government that created it. The Federal Reserve has so flooded the financial system with liquidity that the member owners of the system’s banks no longer need to borrow from it, thus calling into question its very reason for existence.

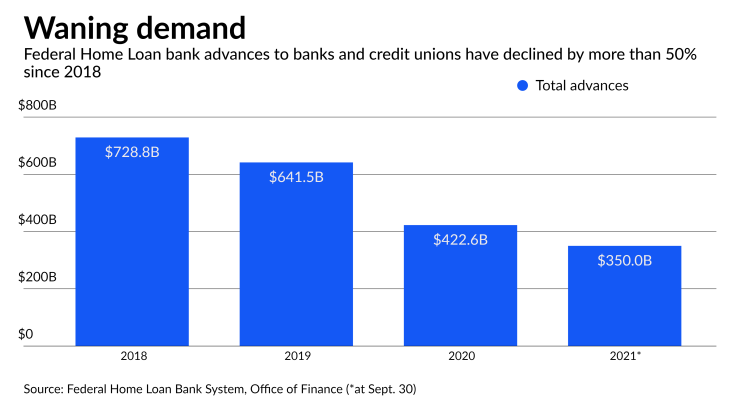

Advances to member institutions, the lifeblood of the system, currently stand at $350 billion. This contrasts with $658 billion two years ago. The system’s assets, over $1.2 trillion during the financial crisis, now stand at about half of that. Not a blip, this precipitous decline in advances and assets is expected to persist in coming years. Moreover, even when interest rates normalize, the system will still face enormous challenges from its members having available to them other competitive sources of funding.

Read more:

Chopra distances CFPB from Trump era in settlement with consumer groups Senators pressed to include cannabis banking in military spending bill

It would be easy in light of its declining use and relevance to consign the system to the fate of, say, the Civil Aeronautics Board and other such agencies of government that outlived their purposes. The Home Loan bank system, however, is different. As one

The question is: Will the Home Loan banks be relevant going forward?

Most would like to see government and quasi-governmental institutions be as lean and efficient as possible. Focusing this efficiency lens on the system at this point in time could easily lead to the conclusion that the system ought to be disbanded or that the 11 banks should be consolidated. Before it is consigned to the bureaucratic dust heap, however, a closer look ought to be focused on its unique business model and how, with modest modifications, it might be repurposed to meet the challenges of the modern era.

The system blends the advantages of federal government support with local on-the-ground insight and control through its semi-autonomous Federal Home Loan banks. Each bank is overseen closely by the Federal Housing Finance Agency. The board of each bank consists of member directors and independent directors from its region. All banks are jointly and severally liable for the obligations of their peer banks, adding a level of self-discipline that is reinforcing. By law and by culture, the system is mission-driven — perhaps even to a fault.

Congress, having created the system, ought to closely reexamine its potential social and economic utility. Such an analysis will likely result in the conclusion that the system’s business model, although outdated, is uniquely suited to today’s financial needs and challenges.

In this important endeavor,

Should Congress choose this more enlightened path of leveling-up the Federal Home Loan Bank System, the framework for doing so is relatively clear. Adjustments needed to restore the system’s current relevance fall into three categories. Those are: mission, membership and collateral. As a guide in examining each category, to paraphrase the late Sen. Robert Kennedy, the most productive inquiry is not “Why?” but “Why not?”

With regard to the system’s mission, why not expand it beyond housing finance to include financing initiatives in the arenas of climate change, infrastructure development and economic equity? The current mission has been narrowly construed by the FHFA and even more narrowly construed by each of the banks. Yet the demands of today’s economy have raced far beyond those of the 1930s.

Regarding its membership, why not open membership eligibility to lenders to the country’s small businesses that create two thirds of all new jobs, fintechs that promote financial inclusion, and nonbanks that originate most of today’s home mortgages? The leveled-up perimeter will include many of these and, besides, banks and credit unions are a dwindling part of the financial system.

As for collateral, why not expand the eligible collateral for system advances to include the many asset classes, in addition to mortgages, that support the new system’s more modern mission? Housing is vital, but so too are roads, bridges, renewable energy, small businesses and sustainable farms. Why not expand the scope of collateral each system bank can accept as collateral for their advances?

Here is the challenge.

The system enjoys an enormous funding advantage. However, change is unlikely to come from within its ranks. Member institutions tend to view their modest ownership interests in their respective Federal Home Loan banks as a claim on each bank’s capital. Members generally fail to acknowledge that the capital of each bank, including over $22 billion in retained earnings, has been accumulated over nine decades largely on the strength of the implied federal guarantee of the system’s debt obligations.

The leveling up process should lead each enlightened member-owner of the Federal Home Loan banks to recognize that the enhanced value of its investment in a reimagined and dynamic system far outweighs any short-term dilution of its current investment in the banks, which are in a state of secular decline. The system will survive through growth, not through one-time expense reductions.

So, change will need to come from enlightened external sources. The Biden administration’s opportunity to nominate a new, forward-leaning leader (including the nomination of the current acting director) to head up the FHFA is one such source. So too are the many and varied players who could benefit from access to a new and improved system. Nowhere is it written that leveling up must be a painful exercise. It can also open many doors of opportunity.

The views expressed are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization with which the authors have been or are now affiliated.