Twelve months after the World Health Organization

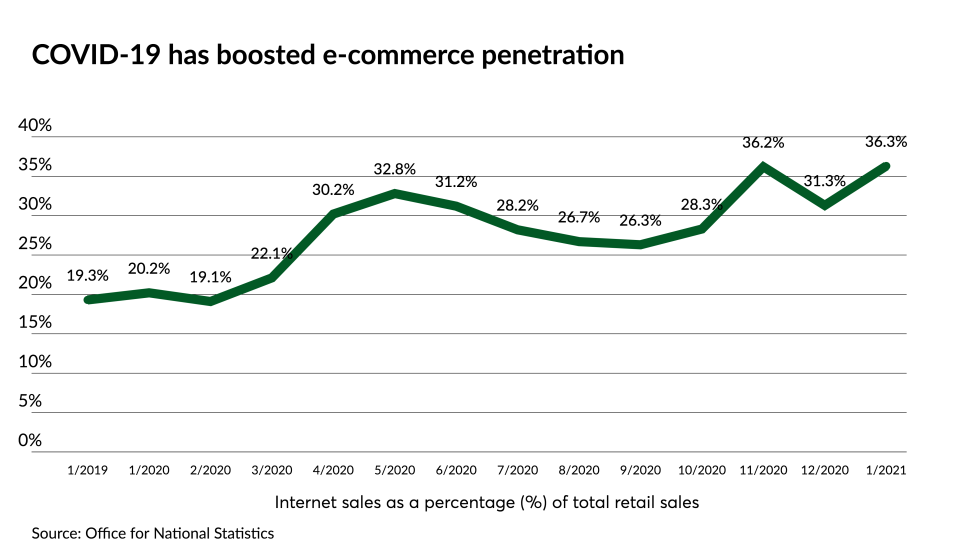

However, as the lockdown subsided and stores began to re-open, the habits of the British shopper had changed, forcing banks and merchants to adjust.

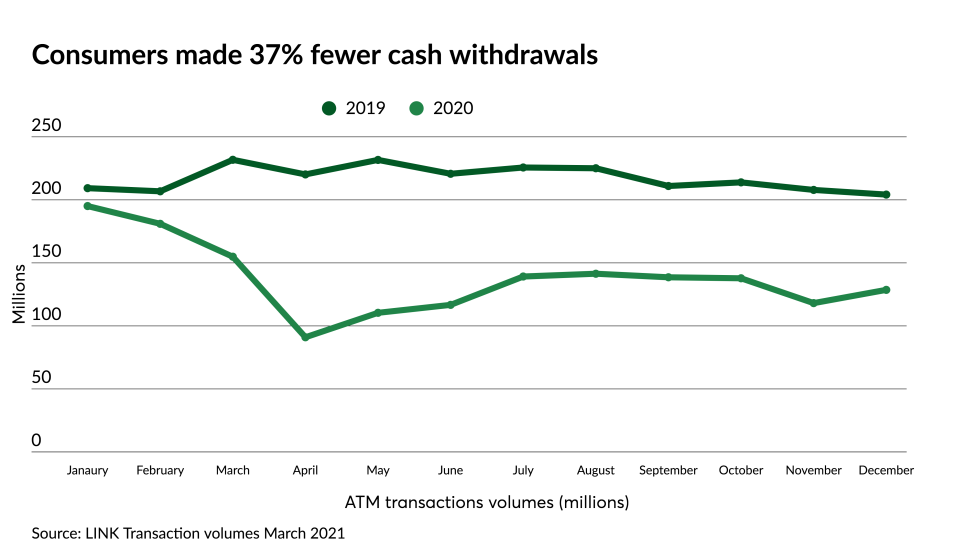

By February 2021, half of U.K. consumers reported that more than 75% of their in-store transactions were made using a contactless payment method, according to a study from