Augmented reality — which scans the world through a camera and places digital constructs on top of it — seems to be the next big thing in mobile technology, with Apple and Google making it a centerpiece of their latest smartphone launches.

The technology itself is not all that new, but its wider support could bring fresh ideas to brick-and-mortar retail.

At the vanguard of AR have been fashion brands such as Sephora, Paul Frank and Max Factor. For these brands, AR has been instrumental in allowing consumers to — virtually — try on clothes and cosmetics in the home, mimicking the experience of shopping in a store. Metrics on a recent Max Factor AR initiative provide compelling evidence on consumers' reception for expanded retail capabilities.

According to Blippar, an AR app provider, 70% of beauty shoppers research online before they buy but only 10% actually purchase online. To overcome this friction, Max Factor launched a pilot with UK pharmacy chain Boots in conjunction with Blippar. Through the use of AR, shoppers were able to see before and after shots of makeup products, alongside common e-commerce tools such as recommendations, beauty tutorials and reviews.

The metrics speak for themselves — during the pilot period from August to December 2016, there were 44,000 users of the Max Factor AR app and as much as a 30% sales uplift in stores with the highest number of recorded AR interactions.

AR has also found a home with the Swedish furniture purveyor

One of the first retailers to use iOS11 ARKit, IKEA Place launched in Mid-September, allowing consumers to virtually test out the placement of any of 2,000-plus pieces of IKEA furniture and accessories in the home. After placing a piece of digital furniture, the app allows users to store photos of them, share and save them, and eventually buy them at a local site.

While fashion and furniture seem obvious categories for AR in blurring online and offline domains, other retail sectors are less tested.

Last week, the embattled toy retailer Toys R Us, began a pilot launch of

"Where the rubber meets the road on AR is when a consumer can move beyond visualization and into purchase," said Michael Moeser, director at Javelin Strategy & Research.

If you build it in AR, will they come?

AR has long struggled to gain traction in a commercial setting. The slow uptake of AR can be attributed to the limited availability of requisite hardware and software that allows this merging of domains. One of the first public AR initiatives was Google Glass, launched publicly in 2014 in limited release and a prohibitive $1,500 price tag. Google Glass was considered too unfashionable to truly catch on, but less ambitious uses of AR such as last year's hit mobile game Pokemon Go have demonstrated the technology's potential; as of February this year, the game had been downloaded 650 million times.

Within Pokemon Go, smartphone owners could scan their surroundings for virtual Pikachus and other Pokemon characters, taking pictures of them and capturing them. The AR feature could be disabled if it proved too disorienting, but it was still considered a major selling point of the app.

Now that Pokemon has demonstrated the mass appeal of AR, retailers are looking for ways to capitalize on the trend. They are aided by Google and Apple's recent launch of two platforms for developing AR capabilities — ARCore and ARKit, respectively.

One of the other significant benefits of the success of Pokemon Go, was in normalizing the activity of AR gamification in public — it is now (mostly) socially acceptable to be hunting virtual trophies in the physical world. With Pokemon Go and other AR applications such as Snapchat filters, AR usage has grown significantly.

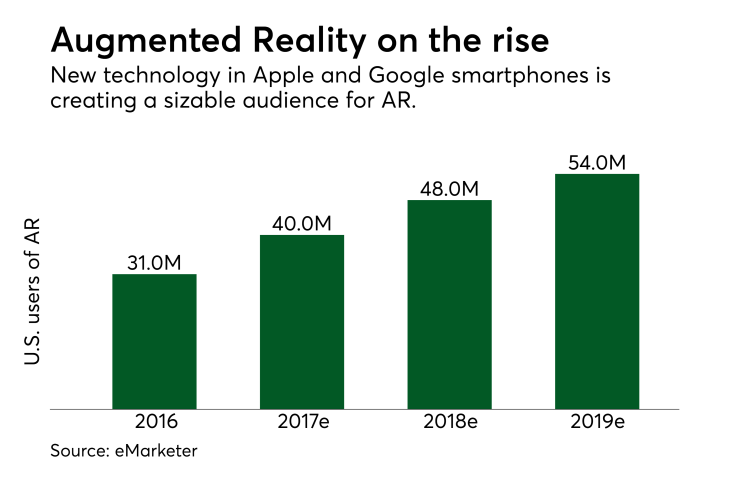

According to eMarketer, AR usage on a monthly basis grew from just over 30 million people in the U.S. in 2016 to over 40 million in 2017, and is set to exceed 54 million by 2019. Further, in a recent study by DigitalBridge, 61% of consumers stated that they wanted to have access to AR in retail.

“The first opportunity for AR in retail is to help customers feel comfortable with purchasing items they haven't seen in person,” said Stephanie Pandolph, research analyst for BI Intelligence. “That's still a big hurdle in e-commerce, and could potentially save retailers a lot of money on returns.”

AR is the new bricks-versus-clicks battleground

Despite hardware and software limitations, retailers have been at the sharp end of AR innovation to counter showrooming and other activities that have steered business to purely online competition.

But e-commerce sellers can use AR just as well. Amazon, the bane of incumbent physical retailers, is also actively pursuing AR capabilities through its range of Echo devices. Notably, the Echo Look, a device touted as a “hands-free style assistant" that can snap pictures of the consumer to compare outfits. This isn't true AR, but it has the potential to add AR on top of this use case to add outfits the consumer does not yet own. And of course, Amazon would then offer to ship those outfits to the consumer's doorstep.

In straddling these two domains, AR introduces some complications. In the Amazon example, the path to purchase is clear; in the Toys R Us example, it's far less obvious how a virtual basketball game can lead to sales of real merchandise.

“In-store payments via AR require significant systems integration, and dealing with some business issues — is it an e-commerce or a physical-store transaction?” says Omaid Hiwaizi, global head of experience strategy at Blippar. The value of AR at this time is in broadening retail touchpoints. “Payments in retail AR therefore are more likely to initially find their place pre- and post-store, making brand touchpoints like posters, catalogs and the products themselves frictionlessly shoppable.”