Over the last few weeks the SEC has clamped down on two initial coin offerings — and in doing so, raises questions about whether shady ICOs are a byproduct of other avenues for cryptocurrency fraud being closed down.

The pace of regulation may be a preemptive measure to protect investors as they become increasingly speculative in the wake of the recent bitcoin buying frenzy — the lure of high returns outweighing understanding of the cryptocurrency landscape.

However, ICOs present a significant challenge to not just the SEC but all financial regulatory bodies. Given the decentralized and borderless nature of cryptocurrencies and ICOs, is policing them ultimately futile?

The SEC bares its teeth

On Dec. 4, the SEC’s newly minted cyber team

It also filed charges against LaCroix and PlexCorps alleging that they sold securities claiming investments in PlexCoin would bring profits of 1,354% in less than 29 days. Afterward, the

That the SEC is making a stand may be about more than securities regulation. Not only can ICOs be set up by criminals as honeypots for unsuspecting investors, the currencies that are being developed can potentially exist in a completely unregulated form and therefore be used as funding mechanisms for illegal activities.

This was much the same for bitcoin in its early days.

The anarchic-by-design currency gained a bad reputation as a means of purchasing illegal drugs, firearms and other contraband on darknet sites such as the now-defunct Silk Road. While the currency itself is virtually impossible to control, the points of cryptocurrency trading can be.

It is likely that newly minted cryptocurrencies stemming from ICOs will be similarly regulated, but given the sheer volume of ICOs, regulatory bodies will have their work cut out in keeping up. Cryptocurrencies stemming from ICOs also present regulators with an additional layer of complexity. These currencies can be purchased using bitcoin or other popular cryptocurrencies and therefore are one step removed from regulator scrutiny — it’s possible to regulate purchases of bitcoin, but far harder to regulate bitcoin purchases.

ICOs unleashed

The SEC does, however, have some clout when it comes to shutting down ICOs. In the U.S., what is known as The Howey Test is often used to determine whether an offering is a security — the four criteria are that the offering be (1) an investment of money in (2) a common enterprise (3) where there is an expectation of profit (4) that comes only from the efforts of the promoter or third party.

This defines most ICOs. But the SEC reach is not international and, to date, the regulation of ICOs represents a patchwork of country-level restrictions varying from soft touch to draconian. Much of this comes down to nomenclature — are digital currencies defined as assets or securities? Switzerland and Singapore deem cryptocurrencies to be assets and regulation is correspondingly light. The U.S. views them as securities.

As a result of this conflicted state of regulation and the word spreading of just how effective they can be as a fundraising mechanism, ICOs have grown meteorically over the past couple of years, with both an increase in the number of ICOs per month and the average value raised by each ICO sale. There were three ICOs in October 2016, raising cumulative total of $13.4 million. In September 2017, there were 35 ICOs which raised a total of $537 million. The average ICO value correspondingly increased to $15 million in September 2017 from $5 million in October 2016.

Quantity, not quality

Of the 232 ICOs that had occurred as of September 2017, a couple that stand out as examples of how successful these sales can be in fundraising — Filecoin and Tezos — both raised over $200 million.

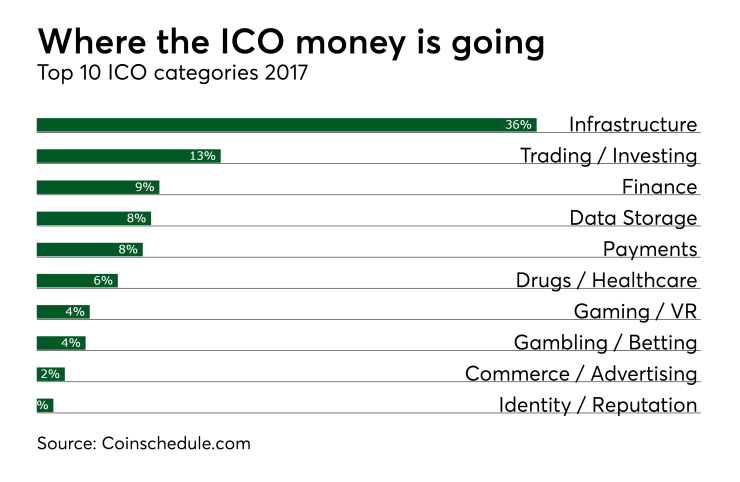

More than a third of ICOs can be categorized as fundraising for blockchain infrastructure projects, but there are a sizable number that are directly in the payments realm (8%) or in categories such as health care (6%) and gaming (4%) where the prime objective is to facilitate payments in gray areas such as unregulated online gambling and the nascent marijuana industry.

However, there is a long tail of mediocre ICOs — 50 raised less than $500,000, and a handful raised nothing. The reputation of ICOs has taken a hit from tales of malpractice, misfortune and ineptitude. For instance, Tezos, which raised more than $232 million with its ICO, is now floundering in a legal no-man's-land with its founders, Arthur and Kathleen Breitman, and the president of the Zug, Switzerland-based Tezos Foundation, Johann Gevers, battling for control. The Breitmans are reportedly looking to access funds they raised in their token sale to fend off class actions filed by investors in the wake of the stalled project. Tezos is also reportedly under investigation by U.S. authorities.

More egregiously, some ICOs have proven to be completely fraudulent. In November, an ICO alleged to be funding a smart contract project called

Payment hustlers

Even more disturbing is that ICOs could be used to develop funding mechanisms supporting hate groups, contraband sales and even terrorist activity. In the wake of the

"Payment hustlers rotate payments methods until the path of least resistance is found,” said Dan Frechtling, chief product officer at G2 Web Services. "This can follow a pattern of A, B, C. Plan A, or 'acquirers,' is initially successful but often leads to a rejection after banks and PSPs discover transaction laundering. This is followed by Plan A1, 'Alternative Payment Methods,' then Plan B, 'bank payments,' followed by Plan C, 'cryptocurrencies.' Payment hustlers look for the most hospitable environment to monetize forbidden e-commerce."

One example of a project designed to circumvent payments gatekeepers is Gab’s plans to raise funds for the development of a "censorship-proof social media platform" via an ICO. Gab promotes itself as a non-politically affiliated anti-censorship platform, and it hosts several high-profile far-right users who have been banned from other social platforms over hate speech or harassment. Post-Charlottesville, Gab's app was removed from both Apple and Google’s app stores.

According to Gab’s chief operating officer, Utsav Sanduja, Gab has raised over $1 million in a "test the waters" campaign for its ICO launch this month and is moving ahead with development of the

ICO regulation — a Sisyphean endeavor

As has been experienced frequently with Internet regulatory problems such as digital content ownership, policing a dispersed global network is near impossible.

"No regulatory body can proactively prevent/stop any setup of a blockchain-based company and the subsequent creation of tokens, as it is entirely decentralized," said Gabriel Wang, analyst at Aite Group. "Now that the U.S. forbids retail investors to participate in any ICOs, and the Chinese government has banned ICOs and cryptocurrency trading altogether, investors outside those two jurisdictions are still very active in the ICO space. Technically speaking, there is no regulatory way to stop this from happening, unless every single regulator in the world does the same thing with the U.S. and Chinese regulators in their own markets."