-

It was supposed to be the week the House Financial Services Committee passed a key part of regulatory reform and the Senate Banking Committee finally began moving forward on its ambitious overhaul plan. Instead, it was the week that regulatory reform took a significant step backward.

November 20 -

Securitizations of consumer loans have rebounded, but whether the business can outlast the government sweeteners that have lured investors back to the market is an open question.

June 19

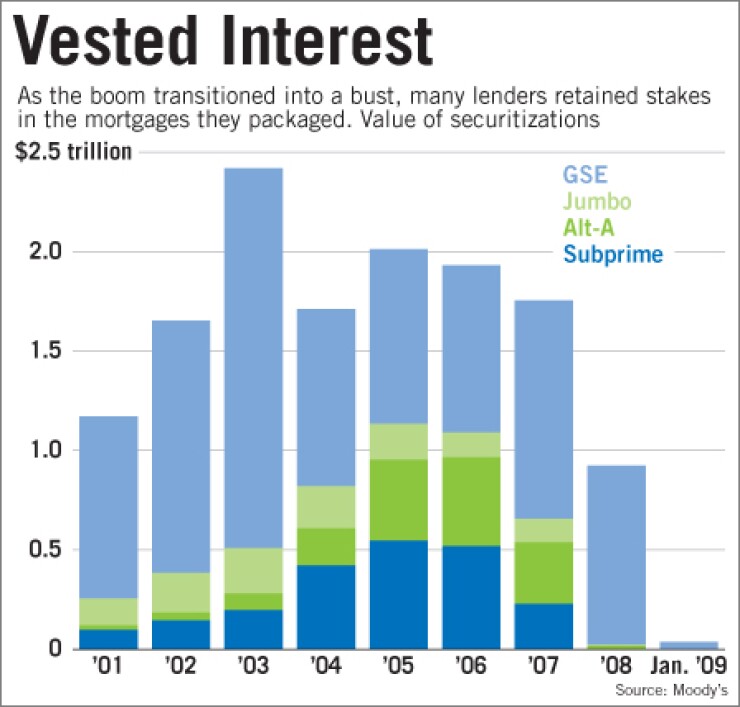

A common diagnosis of the housing debacle is that lenders lacked "skin in the game," and so made loans without regard to risk.

Since they either securitized their products or sold them as whole loans in the secondary market, the thinking goes, lenders had nothing to lose financially if the mortgages went bad.

But those who followed the industry closely during the mid-decade boom years say the story is considerably more complicated. In reality, the lenders that originated subprime, alternative-A, pick-a-pay and other now-maligned loan types retained interests in the mortgages they sold in a variety of ways.

The issue is more than an academic one today. A proposed overhaul of financial regulation being debated in Congress would require securitizers of mortgages to keep, at minimum, between 5% and 10% interest in the pools.

Not surprisingly, many industry members oppose that provision and are sounding some of the usual warnings ("unintended consequences," "harmful to competition," "slowing a market recovery"). Whatever the merit of those objections, the bigger question is whether mandating skin in the game would make any difference in preventing another bubble.

"We're asking people to pay money instead of telling the truth," said Ann Rutledge, a principal at R&R Consulting, a structured finance advisory firm in New York.

Rutledge, a former analyst at Moody's Investors Service Inc., argues that the problem with securitization during the boom years was not that the issuers did not put their own money on the line, but that they did not provide enough information about what they were selling — and that investors and the rating agencies did not demand it.

"It's exhausting to see everybody reinventing the wheel but not focusing on the information," Rutledge said.

During the boom years, lenders kept stakes in loans in a variety of ways. For example, they made representations and warranties to secondary market investors, promising to buy back loans if a default occurred and underwriting errors or fraud were discovered. Lenders also typically kept the lower-rated pieces of their securitizations (though these were often later resecuritized through another now-tainted structure, the collateralized debt obligation).

Besides selling loans, some of the biggest lenders (and biggest casualties) of the era — Countrywide, Washington Mutual, New Century and IndyMac, among others — kept plenty of loans on their balance sheets. None of this provided enough incentive to hinder disastrous lending practices.

The question of how much risk a securitizer should retain might seem moot at the moment. After all, mortgage securitization, as practiced by Wall Street firms and subprime lenders during the boom era, has been moribund for several years now. Nearly all the mortgage-backed securities sold today carry federal guarantees — eliminating the need for subordinated classes of investors to absorb losses before senior bondholders.

But representations and warranties, a standard requirement of secondary market sales long before (and all through) the bubble years, remain so today. Some lenders argue that if they are required to have some sort of skin in the game, promises to repurchase faulty loans ought to qualify.

"Reps and warrants hold the lender liable to repurchase the loan, so we already have money at risk, because if we didn't originate the loan properly, we have to buy it back," said Ron McCord, chairman of First Mortgage Co. LLC, a nonbank lender in Oklahoma City. "There's not a day that goes by that I don't get a request to correct something, make an investor whole or provide evidence that what we did at origination was correct. It's almost a daily occurrence."

New Century Financial Corp., which collapsed in 2007, appears to have had more skin in the game than it cared to admit. In a 550-page report last year, Michael J. Missal, a court-appointed investigator, wrote that New Century's auditor, KPMG LLP, approved improper accounting strategies that allowed the company to avoid accounting for its backlog of repurchase requests.

If New Century's managers knew it was on the hook for faulty loans it had sold to Wall Street, such concerns apparently were overpowered by what Missal described as "a brazen obsession with increasing loan originations."

Attempts to reach Brad Morrice, New Century's former chief executive, were unsuccessful. A KPMG spokesman declined to comment.

Joseph Mason, a finance professor at Louisiana State University, went so far as to argue that if anything, financial institutions had too much skin in the game during the bubble era.

"So far, the stacking of losses has worked pretty well, since banks have taken the first loss and have largely been wiped out before investors," Mason said.

The skin-in-the-game scenario is part of a 1,139-page reform bill that Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd proposed Nov. 10. After running into bipartisan opposition last month, Dodd said he would redraft his reform bill. The House, meanwhile, delayed a panel vote on the legislation, which gives the government oversight powers of systemically important institutions. The House bill would apply only to certain subprime loans and would even allow federal regulators to lower the 5% threshold.

Micah Green, a partner at Patton Boggs, agreed that reps and warrants are one mechanism designed "to keep lenders honest," but said many lenders did not know the extent of their own liabilities.

"What's driving the policymakers is the disconnect between those that originate the mortgage and how the mortgage gets sold in the secondary market," Green said. "Congress wants to ensure there's an economic incentive to be honest in the origination process."

However, Green also said that by tying up much-needed capital, some lenders would be forced out of the business just as the government wants increased lending.

Glen Corso, a founding partner of the Community Mortgage Banking Project, a recently formed lobbying group for regional nonbank lenders, said the 5% retention requirement, for example, should apply only to nontraditional products, such as subprime loans, and not to plain-vanilla mortgages insured by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Housing Administration.

He argued that the proposed rule would force many lenders to either quit the industry or sell their loans to aggregator banks, essentially handing a monopoly to the nation's four biggest banks.

"If you require risk retention even to safe and affordable products, it will seriously disrupt the market," Corso said. (McCord at First Mortgage is the trade group's chairman.)

Tom Millon, the president and chief executive of Capital Markets Cooperative, a Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla., company that provides secondary marketing services to banks, said the skin-in-the-game requirement would "put another nail in the coffin" of private-label securitization.

"Bombshell is the word," Millon said. "No one is going to be in a position to retain 5% risk. They frankly just don't have that amount of capital, and it decimates the economics of the industry."

Ken Kohler, a partner at Morrison & Foerster, said a significant problem with the proposed legislation is that lenders would be kept from hedging the retained risk. "In order to have skin in the game, you couldn't hedge it, because they want to make sure lenders are punished," Kohler said. "That goes against every principle of prudent management of our financial system."

In addition, changes to off-balance-sheet accounting rules, primarily through Financial Accounting Statements 166 and 167, could have a significant impact on lenders' financial statements by requiring that pools of loans that had been held in special purpose entities be consolidated back on to balance sheets, he said.

The proposals will "eat into the profitability of loan sales," Kohler said. "From a bank standpoint, you can't make money," he said. "You can't grow liabilities in a bank" without raising capital.