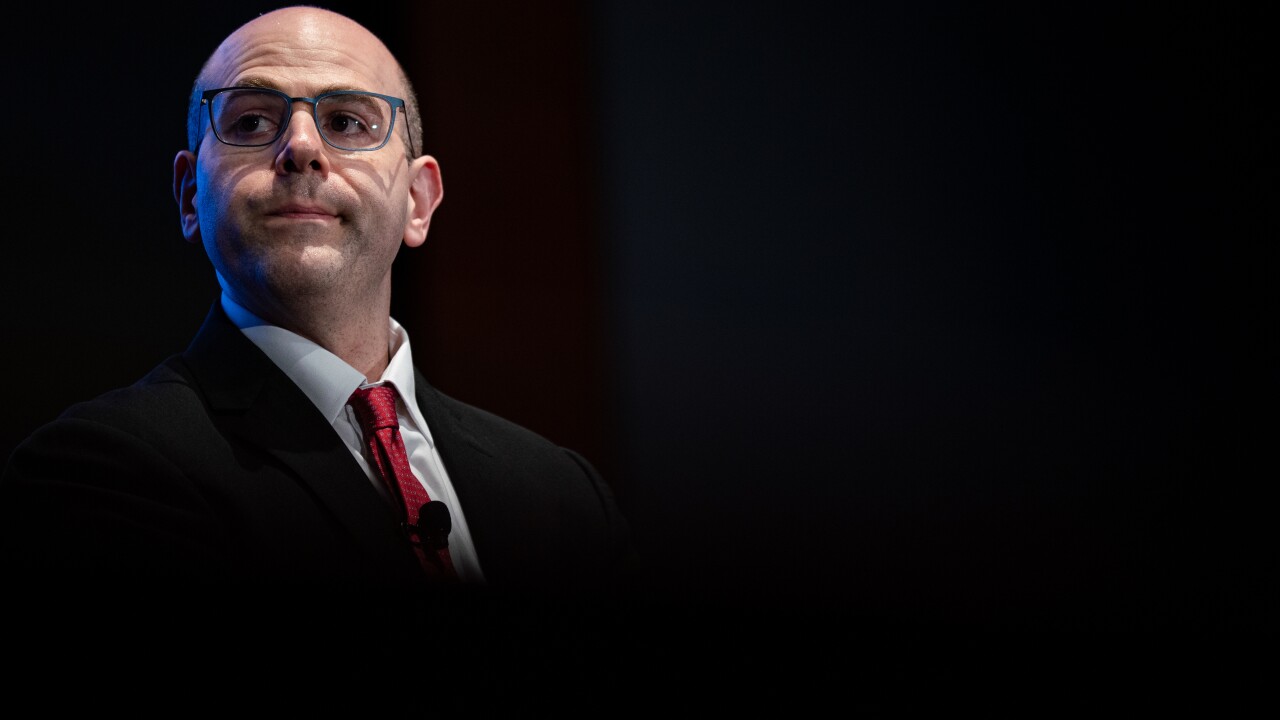

As Glenn Goldman sees it, the practice of small business lending mainly involves the use of imperfect information to make a credit decision, followed by 30 days of waiting and hoping that a portion of the money gets paid back (with the latter step repeating itself over the life of the loan).

"Between each of those payment dates, you're flying blind," Goldman says. "You don't really have any visibility at all into what your customer is doing."

Whether his company's solution to that problem will be enough to close the gap between the amount of credit extended to U.S. small businesses and the volume of lending that Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner would like to see is doubtful. But it certainly offers banks a new way to think about managing risk in their small-business portfolios.

Goldman's firm, Capital Access Network, puts the electronic payments system to work in a way that allows lenders to small- and medium-size businesses to access the daily cash flows of borrowers, and collect daily remittances from them. The platform gives lenders a window into their customers, and relies on payment processors to split the settlement of card transactions between the small business and its bank.

The beauty of the system, Goldman says, is that it gives lenders more, and more frequent, data points to strengthen their overall credit modeling while also helping them to manage relationships with individual borrowers.

Capital Access and its daily remittance platform this year took the "overall most innovative" category in Barlow Research Associates' Monarch Innovation Awards, which recognizes financial industry innovation. One of the judges, Robert Seiwert of the American Bankers Association, says the concept takes valuable information that used to be considered the proprietary information of analytics firms and makes it available to any bank that wants to pay for it.

"If you look at the way we traditionally analyze small-business credit, there's two ways of doing it," says Seiwert, an ABA senior vice president with the industry group's Center for Commercial Lending and Business Banking.

One method, the credit scoring used by bigger banks, is inexpensive to do and can get customers a loan decision quickly. But many of the models "just didn't prove out once the recession came," Seiwert says.

The other method, a more thorough exercise involving reviews of business plans and financial statements, and on-site visits to potential borrowers, is a more customized process and one that might give bankers more confidence going into a new relationship, but it's also an expensive and time-consuming way to underwrite loans.

"What Capital Access has come up with is a third way," Seiwert says. "Instead of waiting 30, 60, 90 days after a quarter is over to get the financial statements, we can get data daily and get into the heartbeat of a business to figure out how it's doing."

Christine Pratt, senior analyst for lending at the consulting firm Aite Group, says banks could use a little added dynamism in their small-business portfolios. "The small-business customer is sticky and is a good customer," Pratt says. But data on this customer set "is not easy to come by, and so the analytics in the space suffer."

That's especially true for businesses in more challenging industries, like restaurants, which banks traditionally view with great skepticism.

Credit scores and other underwriting tools no doubt are weak predictors of consumer tastes. What lender wants to bet on whether the next craze to hit town will involve tapas bars or cupcake shops? But what if a bank determined that a tapas bar owner was a creditworthy borrower, and could monitor the establishment's sales on a daily basis? "If there is a downward trend, if customers are not coming into the restaurant all of a sudden, you can spot that early and take corrective action," Seiwert says. "Or maybe you find that a certain type of cuisine is no longer 'in,' that people have moved onto something else, so you can dial back future loans to those kinds of restaurants."

Capital Access says it already has 13 years'-worth of information in its proprietary database, drawn from tens of thousands of fundings made with its own balance sheet. Until it came up with the daily remittance platform, Capital Access, founded in 1998, was involved mainly in two businesses: AdvanceMe, which makes merchant cash advances tied to future credit-card sales, and New Logic Business Loans, which offers financing to businesses based on Capital Access's own risk-scoring models. "Some of our best-performing customers have FICOs in the 400s, and we're turning down folks every day with 750 FICOs, which most banks are giving auto approval to within 30 seconds of an inbound phone call or web inquiry," Goldman says.

The intriguing part of what Capital Access is doing, Seiwert says, is that it is giving banks a similar ability. "They've migrated this technology to allow banks to use it," he says.

The daily remittance platform was unveiled last October, with a Spanish-language version added a few months later. In March, Capital Access signed up AvanzaMe Dominicana to use the platform for working capital loans made to small and midsize businesses in the Dominican Republic. Goldman says the platform also has been deployed on behalf of a "major" bank here in the United States, but a nondisclosure agreement prevents him from naming names.