Big-data firms pitching alternative credit data are struggling to teach community banks and credit unions new tricks.

Innovative ways of analyzing a borrower’s ability to repay have garnered significant media attention in recent months, particularly in the area of consumer lending.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau joined the debate in February when it began seeking feedback on the pros and cons of using alternative data such as rent or utility payments to make credit decisions. The agency, for its part, believes alternative data could help

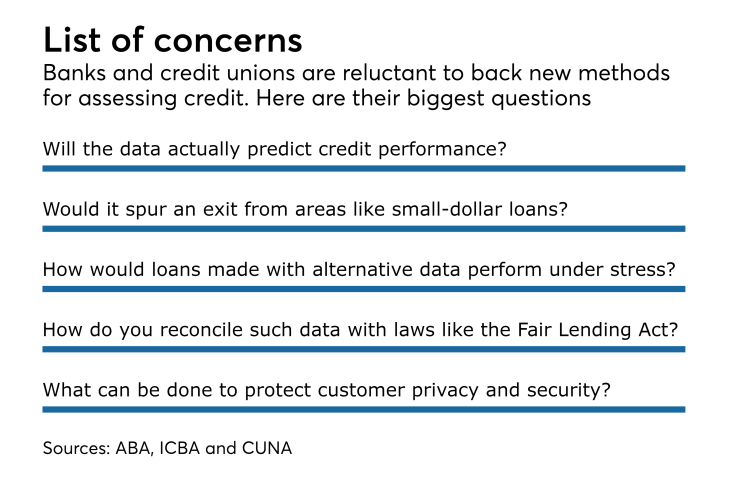

Small banks and credit unions, however, seem reluctant to give big data a try, especially in areas such as small-business lending.

“We’re still working on getting some traction” with smaller institutions, said Ben Cutler, senior director for small-business credit risk decisioning at LexisNexis Risk Solutions. “Some of it comes down to [a lack of] familiarity with alternative data sources and the value they bring.”

Cutler’s observations are backed by a December 2015 study by TransUnion that found that just 16% of banks and credit unions used alternative data during the underwriting process. Many bankers also recall how dabbling in nontraditional credit analysis contributed to losses during the financial crisis.

Bankers also tend to lag other financial services firms when it comes to adopting technology, said Christina Camacho, CEO at Ivy Lender, a nonbank small-business lender based in Miami that uses alternative data to underwrite loans.

“Banks are like a square box,” said Camacho, who spent nearly a decade as a treasury management officer at Fifth Third, JPMorgan Chase and Busey Bank. “They’re very stringent in their underwriting. They just don’t listen to a story the way alternative lenders do.”

Nonbank lenders, which use online business models and often serve borrowers nationwide, tend to be early adopters of alternative data.

“We’re getting customers from all across the United States [and] all kinds of different industries,” said Thomas Depping, a former banker and CEO of Ascentium Capital in Kingwood, Texas. He added that his firm often lacks an existing relationship with an applicant.

“We have about a minute to make a decision,” Depping said. “We do it mathematically and we do it fairly efficiently.”

Community bankers, in contrast, typically lend in specific markets. They tend to base decisions on the so-called five Cs of credit: character, collateral, capacity, capital and conditions. They rely on hard data such as credit history, public records and debt ratios.

Additionally, bankers often require that commercial borrowers meet certain conditions such as having two years of profitable operations. “Since a lot of companies lose money in their first year, that makes it three years before they can qualify for a loan,” Camacho said.

To be sure, strict underwriting helps contain loan losses, but it often works against self-funded entrepreneurs with little or no credit history, industry experts said.

“It’s a hurdle that prevents the bank from converting the applicant to a customer,” Cutler said.

During a recent review of a large small-business lender’s portfolio of about 500,000 accounts, LexisNexis found that two-thirds of the applications lacked a traditional credit profile. Those applicants “were either a big risk … or a valuable opportunity,” Cutler said.

Alternative data has the potential to help small banks and credit unions identify hundreds of lending prospects simply by

Many actions taken by new firms, such as setting up utilities and obtaining a business license, take place without leaving any type of credit footprint, Cutler said, adding that LexisNexis aggregates data from more than 10,000 sources. The firm also beefed up its small-business risk products with data from Cortera, a commercial credit bureau that collects business-to-business payment data.

Those efforts increased the number of surveyed businesses with some form of data from 33% to more than 80%. Of those, one in three businesses “seem to be a good bet,” Cutler said.

Firms such as Ivy Lender also want to reach more of those companies, preferably by working with banks to help applicants they turn down. The referring bank retains the deposit and service side of the relationship and, if everything clicks over a year or two, the borrower should eventually qualify for a bank loan.

Traditional banks and credit unions that rely on relationships and confine lending to a limited geographical footprint may never warm up to alternative data, Depping said.

Depping, who

“We basically have processes and data and analytics, all these things we’ve built up over the last 25 years as to how to credit score a small business,” Depping said.

Community lenders interested in lending beyond existing markets could benefit from alternative data, as long as they are wary of the pitfalls, Depping added.

“You’ve got to be really, really careful,” Depping said. “You have to understand how they put the data together and what it means. … You can’t just jump into a niche. You’ve got to have years and years of data to be able to come up with a solution.”