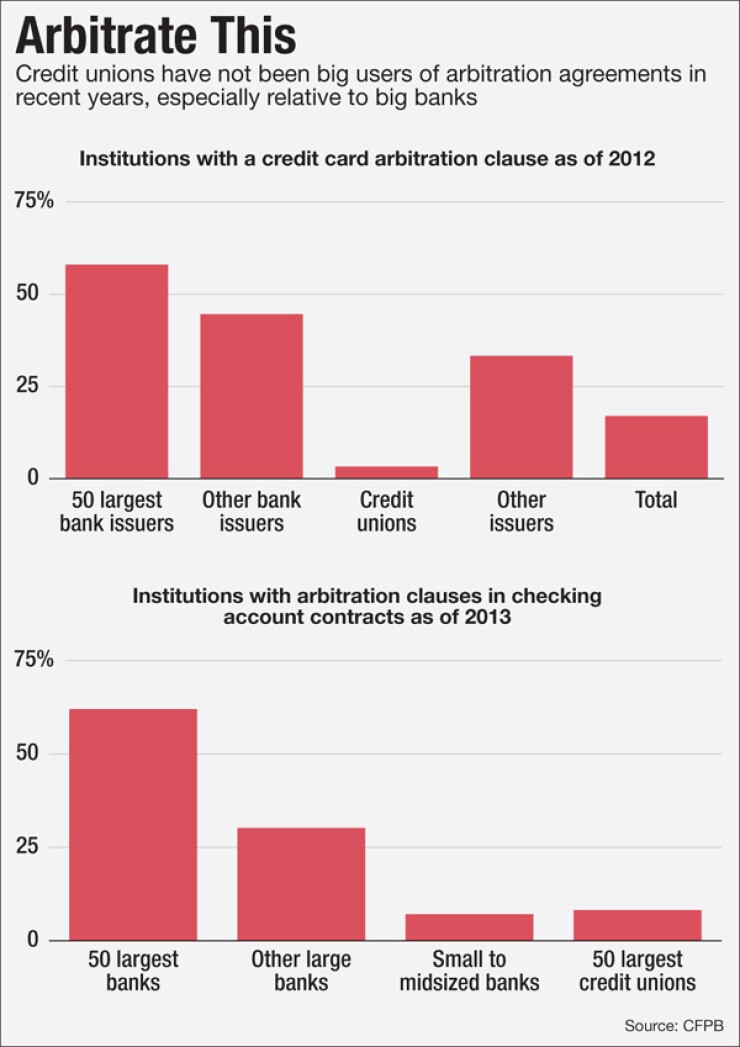

Credit unions are lining up with banks in opposition to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's plan to rein in arbitration clauses, a surprise given their historical reluctance to use them.

Because credit unions are member-owned cooperatives, they are often more closely aligned with consumer advocates' views that consumers should have the right to sue over disputes.

But they have warmed to arbitration clauses in recent years, in part because more credit unions have been hit with class-action lawsuits.

-

Despite fears that increased compliance costs from new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rules could drive community lenders out of the mortgage business, a watchdog report found that smaller companies remain active.

July 25 -

Lobbyists for the credit union industry are decrying a proposal to limit forced arbitration clauses despite ample evidence that credit unions dont use such clauses in the first place.

July 14 -

WASHINGTON Community banks and credit unions would be forced to stop making short-term, small dollar loans if the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's payday lending proposal is adopted, two trade groups said Monday.

June 27

"Credit unions generally stand for consumer-friendly policies but class-action lawsuits are expensive to defend," said Doug Fecher, the president and CEO of Wright-Patt Credit Union in Beavercreek, Ohio. "We've always been able to resolve disputes with our members," but if a credit union "gets a few words wrong in a disclosure, we can be hit with a frivolous lawsuit."

The change in position has not gone unnoticed by consumer advocates.

"It is disappointing the position that credit unions are taking," said Christine Hines, the legislative director of the National Association of Consumer Advocates. "The actions of their Washington representatives are more aligned with the big banks than they are with what their members need, which is the ability to go to court when a dispute arises."

Credit union representatives defend the change of heart, noting they do not support mandatory arbitration clauses – something many banks use. But they are also concerned the CFPB's plan would go too far by effectively getting rid of arbitration altogether.

The CFPB's proposal, released in May, would ban the use of mandatory arbitration clauses that prohibit consumers from bringing class-action lawsuits. Though arbitration could still be used to resolve disputes, banks and financial institutions have said they cannot afford to operate both an arbitration process and set aside reserves for class-action litigation. As a result, many in the industry believe arbitration will simply fall by the wayside.

Historically, credit unions have

Moreover, the Credit Union National Association even has a 2007

Leah Dempsey, CUNA's senior director of advocacy and counsel, said credit unions started putting arbitration clauses into consumer agreements after the Federal Communications Commission issued

That guidance spooked many credit unions because it limits how often a financial institution can contact a customer by phone or text. Many institutions feared the potential for being sued based on how they reached out to customers, and began adding arbitration agreements as a result.

"A credit union could essentially send a text message out to its members and [get hit with] statutory damages from $500 to $1,500 per call, which could put any credit union and its members in jeopardy," Dempsey said.

Bruce Pearson, a senior partner with Styskal, Wiese & Melchione, a Glendale, Calif., law firm that represents 300 credit unions, said arbitration clauses started being used by California credit unions in 2015 after the California Supreme Court affirmed their use following the U.S. Supreme Court's 2011 ruling in AT&T Mobility LLC v Conception.

The court ruled in that 5-4 case that the Federal Arbitration Act of 1925 pre-empts state law and that businesses with class action waivers can require consumers to being only individual claims, not class actions.

"This is not about righting wrongs, it's about predatory behavior by the plaintiff's bar," Pearson said.

As an example, he cited a purported class action against a credit union that alleged harm because consumer disclosures did not delineate between actual and available balances on overdraft charges for which a consumer was charged a $28 overdraft fee.

Without an arbitration clause, settling that individual lawsuit would cost a credit union anywhere from $50,000 to $100,000, Pearson said, with the cost running upwards of $1 million if it were certified as a class.

"If my client writes a $2 million check for attorney's fees and disgorgement, who pays for that?" Pearson said.

Carrie Hunt, the executive vice president of government affairs and general counsel at the National Association of Federal Credit Unions, said credit unions have never supported mandatory arbitration clauses. The distinction is an important one because credit unions have never sought to ban class actions but rather want to maintain the ability to resolve disputes directly with members.

"We want to prevent arbitration from being eliminated as an option," Hunt said. "Our concern" is that the CFPB's proposal "in practice will make people not use arbitration at all."

A recent NAFCU survey found that only 15% of credit unions used arbitration agreements; none were mandatory.

"We are not going to say that consumers should be prevented from the right to sue. We believe consumers should have any right they are entitled to under the law," Hunt said. "Do we think it's a positive thing for plaintiff's attorneys to encourage litigants to file litigation that is baseless and costs our members money? No. Litigation may not be the best option."

Fecher at Wright-Patt Credit Union said that being hit with a class-action lawsuit is an "unproven but legitimate fear."

"It would seem like arbitration clauses would be unnecessary for consumer-responsible financial organizations but these lawsuits can be filed over the most mundane things," Fecher said. "If we make a mistake that injures a member, we're going to make it right."