-

Irene Dorner did a lot to turn around HSBC's troubled U.S. operations following violations of U.S. anti-money-laundering regulations that led to a record penalty, but successor Patrick Burke and a new U.S. compliance chief will have to pick up the recovery at its midpoint and finish the job.

June 16 -

Investors' demands that the country's biggest bank produce better earnings amid costlier regulations are prompting fresh cries to break up JPMorgan Chase.

January 6

Move over, JPMorgan Chase. HSBC is poised to become the poster child of "Too Big to Manage."

New reports that HSBC's Swiss unit aided crooks and tax dodgers may reignite the debate that has smoldered since JPMorgan's London Whale scandal, namely: can the management team of any sprawling megabank keep tabs on every potential landmine at once?

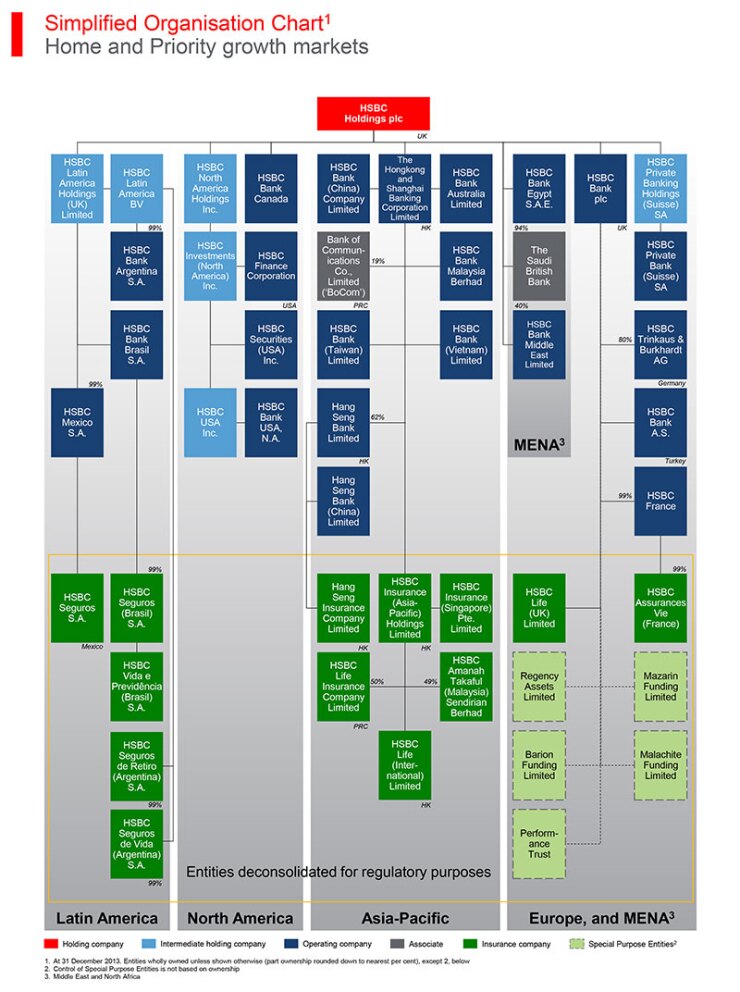

If any bank invites the conversation, it is HSBC: the U.K.-based HSBC Holdings is one of the world's largest financial institutions, with total assets of $2.7 trillion, and one of the most complex, with at least 48 major divisions worldwide. (See flow chart on the right.)

The risks of this model, and the compliance problems associated with it, go beyond the reputational and legal.

HSBC is four years into an overhaul designed to prevent compliance failures, but it is unclear how close the company is to solving its problems. What is clear is that paying for past lapses and preventing future ones has been an enormous drain on HSBC's efficiency.

In 2011, when Stuart Gulliver was promoted to chief executive, he set the goal of a cost-to-revenue ratio (often called an efficiency ratio) between 48% and 52%. That would mean the company spends about 50 cents in noninterest expense for every dollar of revenue; the lower a company's ratio, the better. Later he revised his goal to the mid-50s.

But HSBC reported a 71.2% ratio in the third quarter of 2014, largely because of $2.2 billion of one-time charges, and a ratio of 62.5% through the first nine months of the year. The company is scheduled to report fourth-quarter results on Feb. 23.

Gulliver defended the bank's global business model in a conference call in November, but he also acknowledged that compliance costs are not going away and may put a drag on efficiency long term.

"The fact of the matter is that I think the operating costs to run a global bank of our size and scale today are higher than they were a year or two ago," he said. Gulliver projected a cost-to-revenue ratio in the high 50s going forward.

HSBC's huge investment in risk management has contributed to its rising costs. After HSBC negotiated its $1.9 billion money-laundering fine with the Justice Department in December 2012, Gulliver vowed that the bank would take responsibility for its failings and place a priority on compliance.

Yet there has been no letup in charges for violations - largely, but not entirely, from conduct predating the current management team. Gulliver warned in November that there will be more such charges, as well as higher costs for investments in compliance.

"We can see ahead a continuous need to keep tightening up standards," he said. "We can also see ahead almost an inevitable raft of further conduct charges that will come through."

These "inevitable" charges will add to what is already a long list of expenses for alleged wrongdoing. In the third quarter alone, its charges included $550 million to settle claims that it sold faulty mortgage-backed securities to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, $378 million set aside for a U.K. investigation into possible rigging of foreign-exchange rates and $701 million to redress U.K. customers for alleged violations including problems with loan paperwork. That last charge brings the amount HSBC has set aside for U.K. redress programs to almost $2.2 billion since the end of 2012.

Other massive charges over the past two years include nearly $300 million of litigation costs tied to HSBC's role as custodian for Bernie Madoff's fund, more than $350 million in reserves for investigations into its private bank and $100 million for customer remediation over card and retail services, according to its third-quarter earnings statement.

These charges are painful, despite HSBC's enormous revenue stream. Its earnings of $16.9 billion through the first nine months of 2014 were down 9% from the prior year. The bank's stock has fallen more than 13% over the past year, including a drop of more than 2% since the Swiss leaks were made public.

Aiming for efficiency through cost cuts could be risky, especially when the bank is trying to build credibility with regulators. The U.S. government blamed HSBC's money-laundering failures in part on bank-wide cost-cuts, which left the risk operations understaffed.

HSBC has been adding compliance staff while cutting jobs in the aggregate. Total headcount at Sept. 30 dipped by about 1,500 people from a year earlier, to 257,900, while risk and compliance staff grew by 7%, to 24,800.It may help avoid control failures, but having nearly 10% of the workforce in these non-income-generating functions can weigh on earnings.

On the U.S. side, profit is growing, but compliance questions remain. Fourth-quarter profit for the $280 billion-asset HSBC Bank USA rose 33%, to $558 million, last year, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Yet new CEO Patrick Burke is still trying to complete the unit's overhaul of controls for deterring money laundering and vetting customers.

Burke replaced Irene Dorner as U.S. CEO in November. In another shift of leadership, HSBC last week named Wyatt Crowell, former U.K. head of commercial banking, as its head of commercial banking for the North American operations.

The reform under Dorner has received mixed reviews by the independent monitor for the settlement. The monitor said the bank was "working in good faith to build an effective sanctions compliance program" and had made a "substantial step" in reforms, but needed to improve data collection and sharing, information technology and program governance, according to a July court filing from the Justice Department.

The reports of the monitor, former prosecutor Michael Cherkasky, are not public, but the most recent report is even more critical of the bank's efforts, according to a

And now the parent company is dealing with fresh reports that its Swiss private bank may have helped thousands of customers cheat on their taxes. U.S. authorities are reportedly

HSBC has responded by insisting that the scandal is old news, and that the bank has changed. The huge cache of Swiss customer data leaked this month predates HSBC's compliance reform: it was collected by a whistle-blower in 2006 and 2007, and passed to tax authorities in several countries, including the U.S., nearly five years ago.

"The media focus on historical events makes it harder for people to see the efforts we have made to put things right," Gulliver said in a

In a statement online, HSBC partly blamed the failures of the Swiss bank, which it acquired through the 1999 purchase of Republic National Bank of New York, on organizational disarray and overstretch.

"The business acquired was not fully integrated into HSBC, allowing different cultures and standards to persist," the statement said.

HSBC said it has cut the Swiss private bank to around a third the number of accounts and half the assets under management since 2007, the period covered by the leaks. More broadly, HSBC has exited high-risk businesses, added thousands of risk and compliance staffers and created companywide policies to avoid financial crime, it said.

But has it done enough? Fitch Ratings last week questioned whether such a large company can stamp out violations, while also warning that further compliance scandals could threaten the bank's "stable" bond rating.

"HSBC's management has improved its control framework, which should help adherence with compliance requirements and protect its reputation," the analysts wrote in a research note on Thursday. "But we believe conduct risks cannot be fully averted for such a large and diversified group."

If that is true, more extreme measures might be hard for the management team to avoid.