Recent warnings that hackers could attack companies through their fax machines sounded as alarmist as when TV newscasters tell us that "this common household object could kill you!"

For starters, nobody uses fax machines anymore, right? Wrong. There were 46.3 million fax machines in operation in 2013,

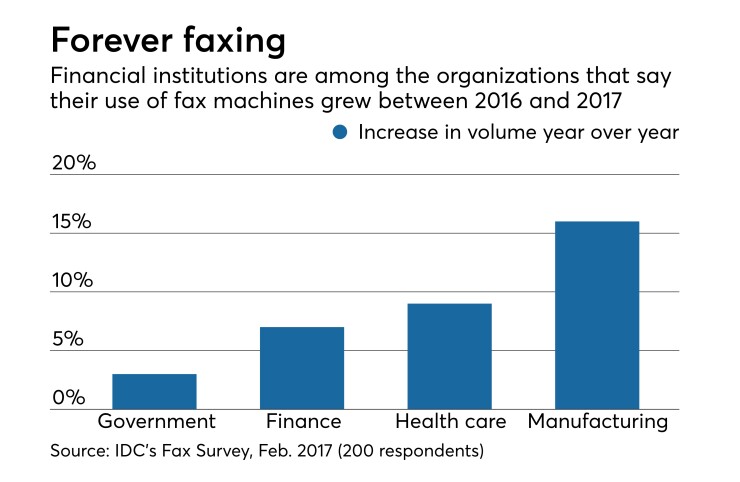

Banks still count on faxes. They and other financial companies told IDC their fax usage had risen 7% from the previous year.

Companies relying on faxes pointed to a variety of reasons, including that clients expect them, they are easy to track, they can be converted to cloud documents — and they have proven to be secure.

Or so they thought. It turns out that hackers could infiltrate an organization's entire network through a fax machine or printer using only a small piece of code, experts say. And it's a concern because some the heaviest users of faxes — financial institutions, health care companies and government agencies — are a constant target for hackers.

Therefore bank security departments would be well advised to take a few precautions to keep their fax machines and printers secure and separate from other parts of their networks.

Peripheral challenge

Though the made-up word “faxploit” is fun to use, this threat isn’t just about fax machines. It is also about printers; multifunction machines that fax, print, and email; and any peripheral connected to a company’s network and can be accessed through a phone line.

Yaniv Balmas, software engineer at Check Point, the first firm to publish research on this, said the company looked at fax machines and other peripherals because they sensed that such machines have been vulnerable to attack for a long time.

“The primary protocol used for fax hasn’t changed for the past 30 years,” he said. “We didn’t see anybody doing any research on this, and that didn’t smell right to us. We look for this kind of thing.”

The Check Point team came up with a type of attack that could fell printers and fax machines. In this attack, the hacker sends a fax containing malicious code. The machine receives the fax with its errant code and uploads it into memory, allowing the hackers to take over the device and spread the malicious code throughout the network.

“Printers are quite often a bridge between the telephone line and the network, because they’re connected to the network through internet or Wi-Fi or whatever,” Balmas said. “The printer can go on from there and propagate the network.”

So hackers can gain entrée through a printer or fax machine into a bank’s internal network and then do virtually anything.

“They have unlimited access to the internal network,” Balmas said. “That’s a scary scenario.”

The Check Point team used this method to successfully break into HP Officejet printers.

It told HP about it, and HP issued patches. It also posted a

“Two security vulnerabilities have been identified with certain HP Inkjet printers,” the company said in the bulletin. “A maliciously crafted file sent to an affected device can cause a stack or static buffer overflow, which could allow remote code execution.”

The company listed dozens of multifunction machines and printers that should be patched. HP did not respond to a request for comment.

To be sure, no one at Check Point has heard of a hacker trying to attack a fax machine or a printer or talk about doing so.

“At Check Point research, from time to time we like to do this kind of research project,” Balmas said. “We try to put ourselves in hackers’ shoes and understand if I was an attacker, what’s the next big thing I would do? Then we create protections or increase public knowledge of the new attack surface.”

Asked if he thought Check Point’s report, which other security companies riffed off of, gives hackers ideas they might not otherwise have thought off, Balmas said no.

“This is a very long debate on responsible disclosure relating to research projects done by us and the entire cybersecurity industry,” he said. “Today there’s broad agreement that these things are good. Would you be happier if an attacker found out about this vulnerability before us? I don’t think so.”

How dire is this threat?

Security researcher Al Pascual said the compromise of connected devices is not high on his list of security concerns but should not be discounted.

“I could see this being an issue in the business banking space where some financial institutions still allow applications to be sent in via fax,” said Pascual, who is senior vice president of research and head of fraud and security at Javelin Strategy & Research.

“That assumes these banks are using actual connected fax or multifunction machines and not some sort of e-fax which dumps these messages in an e-mail inbox. It would be hard to quantify the extent of the risk, nor have I heard of this actually being exploited, but I would take this notice at face value and be sure all my fax-capable devices are patched.”

Avivah Litan, vice president at Gartner, said the issue should be taken very seriously.

“If I was a [chief information security officer] in a bank and I saw this, I would jump on this immediately,” Litan said. “You want to close those open doors that hackers can get into.”

She pointed out that fax machines have been vulnerable for years, and this is one of the many types of threats banks and other types of companies tend to overlook.

Litan has heard of intelligence agencies being breached by Russian hackers through printers and fax machines. She also knows of private Swiss banks whose printers were attacked several years ago. Hackers were able to obtain personally identifiable information and combine it with account information.

“The general principle is that these devices are connected to the internet — printers, faxes and all-in-one machines,” she said. “Most security people don’t think about those printers and fax machines when they secure and segment their network. We all forget. What Check Point pointed out is that all you have to do is call the fax to get in the network. I had never even thought of that before.”

Hackers, who always look for the point of least resistance, are no doubt thinking about this, she said.

How to prevent faxploits

The first self-protective step would be to apply all available patches.

Somewhat tongue-in-cheek, Balmas suggested that banks stop using fax machines and use more modern communications. In truth, this would be nearly impossible to do overnight.

“What you can do is, now that you understand printers can be used as a bridge to your internal networks, you can segregate them, put them in a separate network, so even if somebody manages to break into those printers, it would be confined to the printers, it won’t be able to propagate, so the damage would be very confined,” he said. “It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s the best solution for this.”

Litan said banks can use virtual security segmentation to separate print and fax functions.

“You put controls around that, so any time you go to print or fax, you go through this tunnel that no one else can get into from the outside,” she said.

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at