Talking with Stephen Steinour can feel oddly refreshing, much like stepping into a time machine and going back five years or so to a simpler, happier time. The chairman and chief executive of Huntington Bancshares spends a lot of time discussing branding, product development, cross-selling and—gasp!—loosening underwriting standards, all with an eye toward stealing business from rivals, building wallet share and growing revenue.

If you didn't know better, you might think that the country was no longer in the midst of a devastating banking crisis, or that the $52 billion-asset Huntington hadn't recently survived its own near-death experience. The Columbus, Ohio, company lost $3.1 billion in 2009, buried under a mountain of toxic subprime housing, construction and commercial real estate loans, and its survival was in doubt.

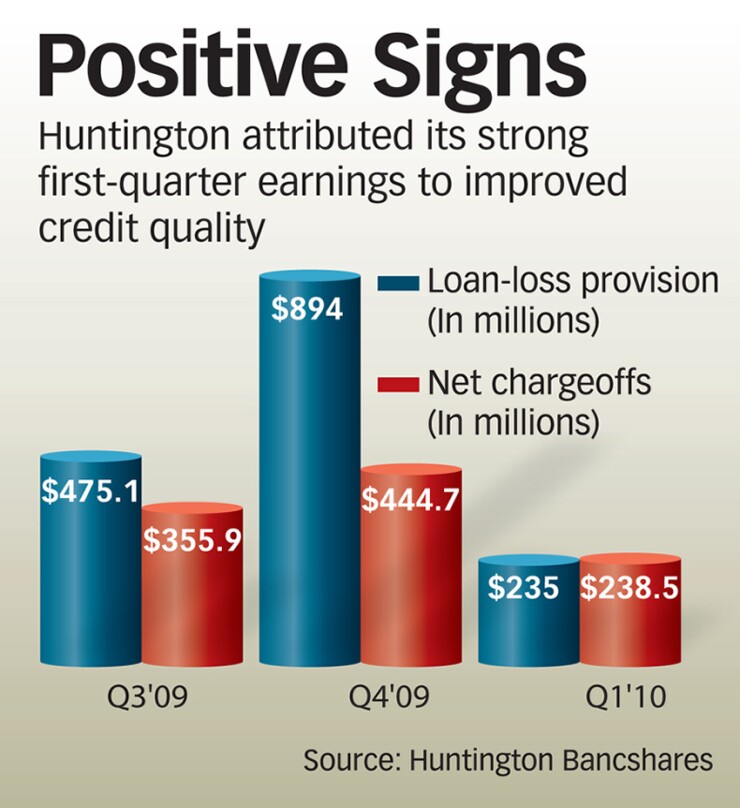

But it is poised for a strong recovery now, asserts Steinour, 51. As proof, he offers up Huntington's surprising first-quarter profit of $39.7 million. Nonperforming assets, chargeoffs and loan-loss provisions all declined. Like others, the company has taken to publishing "pre-tax, pre-provision" income numbers to demonstrate its operating health, and again the news looks good: $252 million in the first quarter, up 12 percent from a year earlier.

Huntington might not be out of the woods yet, but it appears to be a couple of paces farther down the path than most rivals. That, Steinour explains, provides a powerful advantage as banks everywhere ponder how to position themselves for the post-crisis world. "There's a moment here to invest in growth, and we intend to seize it," he says.

Under Steinour, a former CEO and president of Citizens Financial Group in Providence, Huntington has won kudos for attacking its credit woes aggressively. Since he took the helm in January 2009, the company has set aside $3 billion in loan-loss provisions, cut expenses and done deep-dive reviews of the subprime mortgage, commercial real estate and construction loan portfolios that have given it so much trouble. It also has raised $1.8 billion in new capital.

Such moves have revived Huntington's vital signs. In the first quarter, the company's Tier 1 capital ratio was 11.94 percent, while its tangible common equity ratio was 5.96 percent.

Nonperforming assets were still elevated at $1.92 billion, or about 5.2 percent of loans, but the figure was smaller than the quarter before. Net chargeoffs were $238.5 million, or 2.58 percent of total loans on an annualized basis—a 46 percent drop from the previous quarter's levels.

"A year ago, there were some legitimate questions about whether Huntington would still be around," says Scott Siefers, an analyst with Sandler O'Neill & Partners. Today, "survivability is no longer a concern."

Huntington isn't alone in having successfully tackled its credit woes. What's really turning heads is the assertiveness with which Steinour is positioning his company for the future.

"From the day Steve arrived, the message has been to get ahead of the credit and capital problems ... and not wait for those problems to go away before we started investing" in growth, says Daniel Benhase, a senior executive vice president in charge of private banking. "The pace of play and sense of urgency in the company are much higher today than they ever were before."

That high-energy, pedal-to-the-metal approach appeals at a time when external pressures—still-hefty credit problems, Washington's crackdown on fees, higher regulatory expenses and meek loan demand—are placing added pressure on industry earnings.

"The real issue for all banks going forward is, how will they grow coming out of this cycle?" says Fred Cummings, a longtime Huntington follower as an analyst and now president of Elizabeth Park Capital Management, a $30 million fund based in Cleveland that invests in banks. The short answer, at least in the Midwest, is to steal business from competitors.

"What's going to differentiate one bank from another in the next couple years will be how much momentum they have in their core businesses," adds Cummings, whose fund owns Huntington shares. "When you look at Huntington, they've been dealing with their credit problems. But they've also plotted a strategy for revenue growth."

None of this is a surprise to the people who know Steinour well. Larry Fish, Citizens' former CEO and chairman, says his protégé has trained his whole career to be a bank CEO.

"It was always his ambition—almost a destiny—and he was ready for it," Fish says.

During his 28 years at Citizens, Steinour became a "complete banker," Fish says. "He's one of those executives who can tell you how checks are processed, how credit is underwritten, how deposits are priced, how M&A contracts are completed. He knows every facet of the business."

When Steinour took the helm, "a lot of Citizens' executive team bought Huntington stock," Fish adds. "We know what he's capable of."

Ask colleagues to describe Steinour, and the words "intense," "tireless" and "workaholic" come up. With his family still in Philadelphia, he's pretty much all business, all the time—a demanding boss who puts in 15-hour days, expects his charges to know their numbers, and isn't much for idle chitchat or joke-telling. Benhase calls the measurement, tracking and level of dialogue under the new boss "the most intense I've seen in my career." When meeting with Steinour, he adds, "you'd better know your numbers. He expects high things from you."

That Huntington, a perennial also-ran in a recession-battered region with a reputation for sluggish growth and too many banks, is winning accolades as an industry model might be a shocker.

The Midwest has 22 percent of the nation's population, but 44 percent of its banks, says Tony Davis, an analyst with Stifel Nicolaus & Co. In Ohio, home to nearly two-thirds of Huntington's deposits and a 10.9 percent unemployment rate, the list of competitors includes Pittsburgh's PNC Financial Services, Cincinnati's Fifth Third Bancorp and Cleveland's KeyCorp. JPMorgan Chase & Co. and U.S. Bancorp also boast strong Ohio roots.

Long rumored as a takeover target, the 144-year-old Huntington has floated for decades in the murky middle of banks—considered too big to offer the same level of service as a community bank, too small to provide the products and reach of the big guys. It has stubbornly defied the cynics, performing just well enough to retain its independence, but never truly distinguishing itself.

Huntington's recent history has included the botched integration of its First Michigan Bank acquisition in 1997, an ill-fated foray into Florida (though it did exit the state before real estate prices imploded), and accounting troubles in the early 2000s that sparked regulatory investigations and financial penalties.

Former CEO Thomas Hoaglin, an old Bank One hand who took the reins in 2001, mimicked his former employer by introducing a decentralized culture that promoted local decision-making. The plan worked, to a certain extent, with respectable, but not knock-your-socks-off, returns, but also created vulnerabilities.

In 2007, Huntington completed a $2.7 billion acquisition of the Bowling Green, Ohio-based Sky Financial Group, itself a serial acquirer. Buying the $17 billion-asset Sky and its 330 branches boosted its size and promised some big cost savings from branch consolidations. But the deal also included a $1.7 billion-in-loans partnership with subprime mortgage originator Franklin Credit Management Corp.—and the timing couldn't have been worse.

Within months, the Franklin portfolio began to sour badly. In December 2007, just five months after the deal closed, Huntington announced a $300 million charge related to its recently acquired loans. Sky's former CEO—and Hoaglin's heir apparent—Marty Adams abruptly resigned as president.

Hoaglin had publicly stated his intention to step down by 2011; with Adams gone, most analysts assumed he'd stay. Instead, in late summer of 2008 he quietly prodded the board to begin searching for his replacement. The board hired headhunter Spencer Stuart to conduct a national search, and four months later Steinour, who was managing partner for Cross Harbor Capital Partners, a Boston private-equity shop, emerged at the top of the list.

Steinour says the company's troubles were "part of the allure" of the job. Huntington hadn't been aggressive enough on its credit issues, he says, and also had an opportunity to grow. As a former competitor, "I knew that, historically, it's always been very difficult to pry a customer away from Huntington."

On the flip side, Huntington's board was impressed with Steinour's background, including a stint early in his career with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and his connections with the investor community. "Steve was the complete package," says David Porteous, the company's lead director and head of the search committee that landed Steinour. "When we overlaid his experience with our needs, it was very evident he was the right person."

The initial going was rough. The week Steinour's hiring was announced, Huntington's share price plunged by nearly a third, to near $4. Within two months, it bottomed out at about $1. This was early in 2009, and the entire industry was in turmoil over the economy, government stress tests and the like. Even so, "seeing a new CEO really spooked a lot of investors," Siefers says.

Almost immediately, Steinour went to work, biting the bullet on loan-loss provisions, overhauling Huntington's relationship with Franklin and cleaning up the balance sheet. In his first six months, he laid off more than 500 employees in a cost-cutting move, slashed the quarterly dividend to a penny and raised about $1.8 billion in badly needed capital.

Steinour also installed two new board members, both with banking experience, and hired a number of key managers—including those in credit, strategy and development and commercial real estate. Others were let go. "We had some individuals who let the company down in our risk area," he says. "They're not with the company any longer."

The entire organization was restructured to foster better controls and accountability. Commercial real estate, which previously had been part of commercial banking, became an operating unit of its own. In the retail-banking group, the number of district managers dropped from 51 to 32.

Post-crisis, risk-management has been a high priority. One of Steinour's first hires was Kevin Blakely, former president of the Risk Management Association, as chief risk officer. Business units have been imbedded with their own risk-management officers.

Those teams pull together audits and exam data, but also spend time "process-mapping everything ... so that everyone understands what moderate-risk and low-risk mean," says Mary Navarro, senior executive vice president for retail and business banking.

Big-picture risk-management goals were set, such as reducing the loan-to-deposit ratio (it has dropped from 108 percent a year ago, to 92 percent today), backed by changes to incentive plans. "We used to be a loan machine," Navarro says. Last year, the incentives on selling checking accounts were doubled, while lending targets were tamped down.

Individual units have goals of their own. The CRE team, for instance, has broken down present-day problems in its $7.5 billion portfolio into "core" and "noncore" segments.

The approximately 60 percent of the book considered core—or worth keeping—is treated with kid gloves; noncore loans, including those outside of Huntington's geography or risk tolerance, are handled more aggressively.

Business line heads are held accountable for their troops' results, but they also have help in the form of greater centralization. It's now part of the process for higher-level executives to sit around the table and critique how one manager's initiatives might impact the greater whole.

"Before, we had each group making its own decision," Navarro explains. "By the time you rolled it all up, the overall company might have had a higher risk profile than we wanted."

Halfway through 2009, even as the company was still working through its credit problems, Steinour put senior management to work on a three-year strategic plan, with an eye to capitalizing on the disruptions in the marketplace and growing revenues. While somewhat counterintuitive in the midst of a crisis, "being able to say, 'We're going to set some growth goals and invest in the business,' had an energizing effect on employees," Benhase says.

Huntington had strengths to build on, including a highly rated online banking platform and strong customer-service rankings. Some product lines were targeted for enhancement. One example: foreign exchange, where officials saw an opportunity to build on relationships with middle-market clients.

Another is small-business lending, where Steinour has committed to relaxing Huntington's underwriting standards, with an eye to doubling originations by 2012, to about $1.5 billion.

Steinour offers as an example an otherwise solid small business that lost money in 2009, due to the economic conditions, but now is turning a small profit. "Historically, that's not a loan a lot of banks would make. But it's a smart, prudent business decision to find those [clients], make sure you understand the circumstances, and then get behind them and make some loans," he adds. "We need to restart the economic engines."

In a part of the country saturated by banks, getting more business from existing customers has emerged as a top priority. "Cross-sell is the mission of the company at this point," Benhase says, noting that incentive plans and measurement all have been reworked to emphasize working together to get more business from individual clients.

"You can't opt-out," he says. "There's an insistence and accountability about working together."

Those initiatives have been backed with technical support and spending. A new customer relationship management system, for instance, is being installed to replace five different systems presently in place around the company.

In recent months, Huntington has hired about 500 people—roughly the amount it cut early last year. It also has renewed the lease on its headquarters office, ahead of schedule, opened six new wealth management offices and boosted its spending on corporate marketing by 36 percent in the first quarter versus a year earlier.

"I've been asked many, many times to grow retail 15 percent year over year, while also cutting expenses," Navarro says. "This is different. We're getting support to achieve our goals."

To promote his agenda, Steinour has become cheerleader-in-chief, making near-quarterly bus journeys around Huntington's six-state franchise to transmit his energy and answer questions in town hall-style forums.

All of these are first steps, and it's frankly too early to say for sure if they will produce lasting change. But it seems clear that Huntington will emerge from the financial crisis better off, its independence more assured than it was before. For the third quarter, Steinour is openly targeting pre-tax, pre-provision earnings of $275 million, which would mark a nearly 10 percent increase from first-quarter levels.

Some analysts predict it won't be long before Huntington heads out on the acquisition trail. "The beneficiaries coming out of this cycle will be the banks that are positioned to be consolidators. Huntington is a candidate to be one of them," Stifel's Davis says.

Steinour "has set some aggressive objectives and been relentless in achieving them," Davis says. "In the process, he's turning Huntington into the best bank it's been in several decades."