The chief risk officer is in the ascendancy at precisely the moment when — on the surface, at least — the financial industry seems to have suffered a widespread failure in risk management.

A position that rarely existed a decade ago has infiltrated the executive suite, as bankers entering new businesses increasingly confront a kaleidoscope of hazards. Credit risk has become almost mundane, and only another element in a dizzying taxonomy that includes market, interest rate, liquidity, operational, reputational, litigation, and compliance risk.

It is increasingly clear that identifying these risks, and deputizing officers to manage them, have not made bankers immune to them. Since the credit crisis emerged this summer, banking companies have taken huge earnings hits from mortgages, leveraged loans, and a variety of structured-finance vehicles. The mind-blowing scale of these charges has led to a good deal of consternation about chief risk officers. That they have not eliminated exactly the type of problems that have emerged in recent months has caused some second-guessing of the industry's conviction of their importance.

But that may be because of pervasive misunderstanding about what bankers expect their chief risk officers to do — and the fact that these executives' greatest victories tend to be greeted with silence.

"A chief risk officer can make plenty of great decisions that lower risk and save money, but the problem is you're always proving a negative," said Eugene Ludwig, a former comptroller of the currency. "It's like being the goalie on a soccer team. You know some balls are going to get through, and you're going to get blamed for it. And it's not your job to score goals."

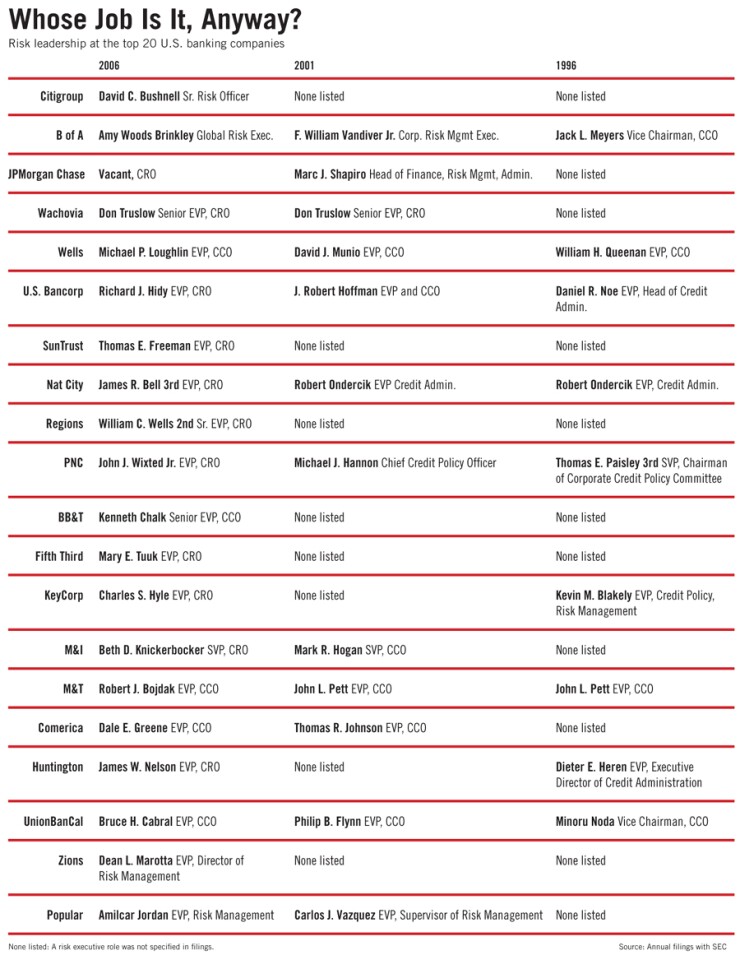

A decade ago just five of the 25 largest commercial banking companies had officers in the executive suite whose roles extended beyond the loan book to include comprehensive, enterprisewide risk management. Another 12 had chief credit officers at that level. Some of the rest employed officers who held similar roles but were buried deeper in the management hierarchy. Five years ago seven of the top 25 had chief risk officers at the executive level.

At the end of last year 19 of the top 25 had chief risk officers; the rest identified chief credit officers at the executive level. One currently has a vacancy — JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s chief risk officer retired at the end of last year. "Until his replacement is named, the firm's chief executive officer is acting as the interim chief risk officer," the company said in a March 1 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

By most accounts, James Dimon is doing fine. His company is generally esteemed to have done an admirable job — so far — of controlling the risks of investment banking.

Large commercial banking companies have embraced chief risk officers more readily than the bulge-bracket investment banks of Wall Street. Though these firms variously identified officers with broad risk management responsibilities, American Banker's review of annual filings made early this year with the SEC by Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc., Lehman Brothers, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley, and Bear Stearns Cos. found that not one identified a chief risk officer at the executive level.

That has changed as events have unwinded in recent months. On Sept. 20, Lehman said its chief financial officer, Chris O'Meara, will become the global head of risk management Dec. 1, reporting directly to Richard Fuld, the CEO. Also in September, Merrill named Ed Moriarty its chief risk officer, reporting to Greg Fleming, the co-president and chief operating officer.

"Banks have been pushed and prodded by the regulators for at least the last decade to improve their integration of their risk management approach," said J.H. Caldwell, who leads the banking practice for Deloitte & Touche LLP's regulatory and capital markets consulting group. "They are more sophisticated, a little more evolved and developed, than the investment banks, where you have typically dealt a little bit with a trader's mentality."

But even at the commercial banking firms, the ubiquity of C-suite chief risk officers is relatively sudden, and the role has evolved as the ranks have grown. In the 1990s "chief risk officer" was nomenclature in a job description that frequently had little substantive meaning.

"The early imprimaturs of risk officers were simply a gathering of all the disparate pieces and parts of risk in an organization under one umbrella," said Kevin Blakely, the chief executive of the Risk Management Association. "It was usually the chief credit officer — even if they didn't know a hill of beans about managing the balance sheet or interest rate risk or compliance risk."

First-generation chief risk officers generally were perceived as data monkeys armed with spreadsheets and barbaric models, and they were frequently disdained as troublesome obstacles for the rainmakers to outmanuever. Their counsel about the wisdom of deals often went unheeded.

But today a chief officer is expected to be a "consigliere with good data sources," said Mr. Blakely, himself a former chief risk officer at KeyCorp. "The optimal risk manager is someone who has very high stature within the company, and a great deal of authority, without having to exercise it. They have the authority to say no when it is appropriate, but they shouldn't have to exercise it, because they can provide such good data that the people taking the risks can make the right decision on their own."

The data is much richer than it once was, and the models are more precise. Developments in measuring economic capital have lent a degree of sophistication in comparing the risks and rewards of disparate business lines. That makes it easier for companies to decide which businesses get fed, and which are starved — or put out of their misery. And it has motivated business-line managers to make decisions that benefit the corporation and its shareholders, not just the business line.

"When you put economic capital into place and tie incentive compensation to it, business-line managers start making different decisions, and that's the way it should work," Mr. Blakely said. "You don't want the risk management office making all the decisions, or an abdication of responsibility for risk back to the risk officer."

Whatever else the chief risk officer's evolving role entails, speaking with reporters apparently is not a priority. Requests to 12 of the country's largest banking companies and five investment banks yielded only one chief risk officer who consented to an interview.

And despite the evolution and sophistication of risk management, outsiders generally cannot determine a chief risk officer's competence. The job still is not described uniformly, and bankers give them varying degrees of hierarchical authority — whether they have, in the words of one risk officer, the authority to "throw the red flag." Regardless of the job description, a chief risk officer has little ability to control risk without the chief executive's explicit support.

"You can have a situation where the CRO wants to go one way but is overruled or undercut by the CEO," Mr. Blakely said. "The culture in the organization may not be supportive of the CRO's initiatives."

In other words, the chief risk officer's responsibility is to tell business-line managers and the CEO when to stop dancing. Whether the CEO gets off the dance floor is an entirely different matter. In the current risk-laden environment, every financial company is paying emphatic lip service to risk management, but that does not mean they all have committed fully to an empowered chief risk officer.

"On the surface, you probably can't figure it out — you just see the title, a designation, a disclosure in the financial statements, and a structure for how people address risk," Mr. Caldwell said. "You don't really know that unless you understand the culture of the organization and its inner workings."

Chief risk officers also make a sharp distinction about their job, which they say is not to eliminate risk but to make sure the company is compensated for risk. As recent events have shown, that goal can be trumped by macroeconomic and financial considerations that go well beyond the officer's purview.

Until this summer's crisis, a global liquidity glut had distorted the usual relationship of risk and reward.

"The flat yield curve is in a sense the culprit here," Mr. Ludwig said, now the chief executive at Promontory Financial Group LLC. "You couldn't make money without going out on to the risk curve and being paid less than you ought to be paid for the risk you were taking."

In fact, the current litany of charges, writedowns, and elevated loan-loss provisions has raised the volume of the discussion of tail events — small-probability occurrences that can have devastating effects on companies.

"The area of risk management that is weakest internationally is analysis of and tactics to deal with the tails, and it turns out that the tails are fatter than most people think they are," Mr. Ludwig said. "It is an important frontier that these companies need to conquer, because you lose all your money in the tails."

It's easy to say now that easing mortgage underwriting standards last year as housing prices started to show weakness maybe was not the best strategy, and the flaws of extending risk-laden loans at no-risk pricing is self-evident now. But withdrawing from the field and watching competitors poach clients is no simple task. Charles Prince may have been alone in bad judgment when he asserted his firm's preference to keep dancing, but the dance floor itself was elbow-to-elbow.

The salad days of banking from 2003 through 2006 led to extremely high expectations in a market that seems increasingly impatient.

"A large banking entity that is being run very safely and returning 14% a year is doing well, but the way the marketplace works, that is not always good enough," Mr. Ludwig said. "Your shareholders are going to pillory you. And that is inherently unholy — it's worse than irrational. You cannot grow at those rates every year, and yet there is so much pressure on the CEOs to make this constant growth return."

That pressure inevitably takes a toll. The prospect of falling short of earnings targets compels companies to devour rewards with little regard for risk.

"Where multiple firms are taking similar large losses, you could say that's a learning event," Mr. Blakely said. "The industry may have less experience in a particular area, understand it less, and expose itself to greater-than-expected losses when the defining event takes place. Usually the industry responds with some kind of enhancement to its risk processes to lessen the impact next time around."

That means chief risk officers can be expected to master the risks of the last cycle, and dampen them in future cycles. The problem is, future cycles always seem to carry new risks. That, in turn, implies another learning event.