-

Abolish the public/private hybrid model of Fannie and Freddie, sell or liquidate their businesses, and privatize the mortgage market. This can be done in an orderly way in a few easy steps.

March 20 -

Although lawmakers were ostensibly there to discuss the nominations to lead the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Securities and Exchange Commission, the debate over "too big to jail" continued to dominate a Senate Banking Committee hearing on Tuesday.

March 12 -

Proponents of breaking up big banks trumpet Attorney General Eric Holder's complaint that some are too large to prosecute. But indicting companies for individual employees' actions would indeed be reckless.

March 11 -

Attorney General Eric Holder's stunning admission that it was difficult to prosecute large banks because of the potential economic impact adds significant ammunition to those seeking to break up such institutions.

March 6

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder hesitates to prosecute criminal violations at large corporations, fearing it could disrupt the economy. "Too big to jail" produces calls to break up large financial institutions and dominates a Senate hearing on the nominations to head the Securities and Exchange Commission and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. What’s going on?

Corporations don't commit crimes or fraud. People do, and when they do they should be prosecuted. Prosecuting people deters future malfeasance far better than prosecuting corporations.

Justice must be blind to race, gender, ethnicity and station for a democracy to retain the trust of the governed and function properly. It's not the job of prosecutors to worry about disrupting the economy. It's their job to apply laws equally.

An overriding issue needs to be addressed comprehensively: Government oversight of financial companies has not worked well in the past, is not working now and little is being done to make it better in the future.

Ineffective regulation is worse than no regulation at all because it creates a false sense of confidence that government is ensuring regulated firms are complying with laws and have the public interest at heart. This misplaced sense of confidence causes people and markets to be less diligent than they otherwise would be.

We have witnessed three major financial crises in our careers. After each crisis, regulators contend they lacked authority to prevent it. Burdensome new laws and regulations are adopted and politicians and regulators assure us they now have all the authority necessary to prevent future crises.

But it does happen again and again! Let's recall the recent subprime financial crisis and ask a few questions.

What authority did the bank regulators lack to rein in the risks taken by the financial institutions that precipitated this crisis? Hint: The correct answer is none.

What authority was the SEC missing to curtail excessive risk-taking and grossly inadequate capital and liquidity plans at investment banks? Or to properly regulate the rating agencies, whose AAA ratings on some subprime mortgage portfolios exacerbated the financial crisis? Or to overrule the Financial Accounting Standards Board, which insisted that banks mark-to-market their portfolios even when the markets ceased functioning, needlessly destroying some

Why didn't Congress rein in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and their bulging portfolios of risky assets despite repeated warnings by experts? The housing crisis could not have grown large enough to endanger our entire economy but for Fannie and Freddie.

Why didn't the Office of Thrift Supervision – the primary regulator of Washington Mutual, Countrywide and other failed S&Ls that were major originators of risky subprime mortgages – do its job?

Finally, why didn't state regulators properly regulate and prosecute mortgage brokers who committed fraud by falsifying mortgage applications? A majority of all subprime mortgages were originated by state-regulated brokers.

The 2,500-page Dodd-Frank Act will likely spawn over 20,000 pages of new regulations and yet does almost nothing to correct these regulatory failures. The Dodd-Frank bill ignores the fact that regulatory failures turned what should have been a manageable problem into a worldwide financial and economic crisis resulting in the longest recession and most tepid recovery since the Great Depression.

Roughly 20 financial institutions perpetrated the recent crisis. About half were investment banks and the other half were S&Ls. Only one, Citigroup, was a commercial bank which had largely morphed into an investment bank prior to the crisis. These firms failed in every respect, from business strategies to ethics. There is no excuse for their behavior or for the regulatory failures that tolerated it. Over 100 full-time regulators are assigned to Citigroup. Why did they fail to deal with the risks?

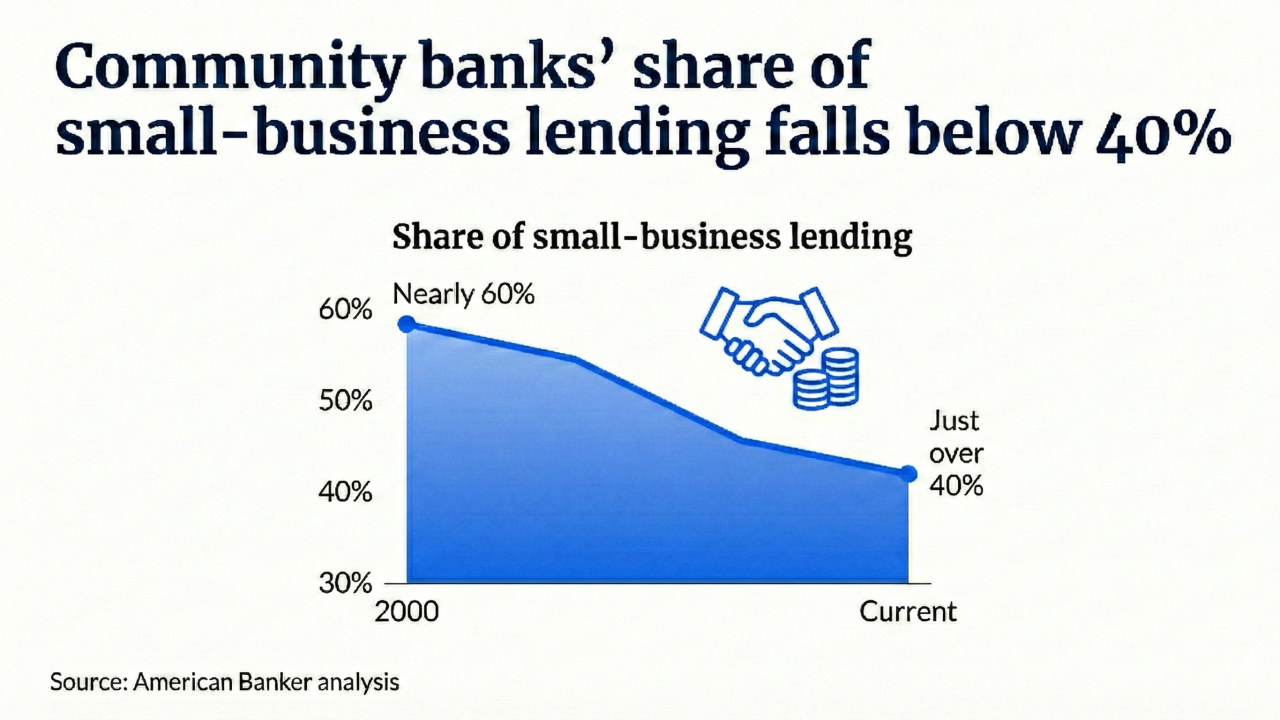

Seven thousand commercial banks are now subjected to Dodd-Frank's penalties and burdens in the same way as the twenty guilty parties. Sadly, many smaller banks may become extinct due to the costs of complying with these new regulations. And millions of individuals and small businesses – particularly those most in need – will be denied or will pay higher prices for loans and other banking services.

Regulators had all the powers they needed to detect and control malfeasance in the financial system – they lacked the political courage and will to enforce the law. The people responsible in both the public and private sectors must be held accountable for these failures.

A highly fragmented and politicized regulatory system needs to be restructured and we must find ways to impose greater market discipline and end "too big to fail". It can be done, but Dodd-Frank has made matters worse, not better.

Richard M. Kovacevich is the retired chairman and CEO of Wells Fargo. William M. Isaac, former chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., is a senior managing director and global head of financial institutions at FTI Consulting, the chairman of Fifth Third Bancorp and author of