-

By purchasing Bonneville Bank, prepaid company Green Dot will be putting itself under the scrutiny of traditional banking regulators. But it may escape increased oversight from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

November 29 -

The Fed's approval marks the first time a prepaid card company has been allowed to buy a bank. Fed Gov. Duke objected, warning that the deal was too risky.

November 23

MONROVIA, Calif. — For the past twelve years, Steve Streit has relished his spoiler role among bankers. But now he has joined their ranks.

The Federal Reserve Board last month gave Streit's company, prepaid card marketer Green Dot Corp.,

The deal, which

"My first reaction was the shock of it. I was quite emotional about it,"

Streit said during an interview early this month at Green Dot's modest Monrovia headquarters. This quaint town 20 miles outside of Los Angeles is adjacent to Pasadena, where Streit moved two decades ago when he was working for a local radio station. A single father with six children, including four adopted daughters, he says a search for a good public school system brought him to the area.

Outside Green Dot's offices, the Monrovia streets are lined with American flags, as if to aggressively repudiate the company's association with the sometimes-unsavory shadow banking system. The venue would make a fitting setting for Streit's marketing pitch.

The former program director at radio station KBIG-FM 104.3 in Los Angeles is still "an amazing talker," in the words of D.A. Davidson & Co. analyst John Kraft. These days, Streit talks about prepaid cards as if they were as American as apple pie.

"Our customers are mainstream America. Firefighters and police officers, teachers, administrative assistants," Streit says. "These are folks who maybe would like to use a bank but they can't, for different reasons."

His task now is to expand the products and services Green Dot sells to so-called underbanked consumers — the poor, young and immigrants who do not have, or do not regularly use, traditional bank accounts — while submitting to the watchful eyes of bank regulators.

He still can't resist taking a few jabs at bankers, even as he is in the process of becoming one. New products and services from Green Dot will be "highly disruptive" to traditional banks, Streit says, though he declines to provide details.

"Anyone who thinks financial services can't be fun and innovative is wrong," he says.

As many of Streit's new banker colleagues might caution, boring is sometimes best. Consumer advocates have criticized prepaid companies for the high, often-opaque fees they charge customers, and have urged the new consumer financial protection bureau to

Michelle Jun, a senior attorney for Consumers Union, the advocacy arm of Consumer Reports, says prepaid cards do not have the same protections against loss or fraud that traditional debit cards do, particularly when it comes to unauthorized transactions or mistakes made by merchants. Another big problem is that most fees are not disclosed on the packaging.

"Typically a consumer will load money onto a card and then get a fee schedule in the mail that shows it's a lot more expensive than they expected," she says.

Prepaid cards look like traditional debit cards, but they allow consumers to load funds or set up direct deposit to load money directly onto their cards without having access to traditional checking accounts. Green Dot's customers can then swipe their cards just as they would a traditional debit card. That includes the ability to make purchases and withdraw money from ATMs — for at a price. Green Dot charges $2.50 for out-of-network ATM withdrawals.

Green Dot customers typically pay $5 for a card and a $5.95 monthly fee that is waived if the consumer loads $1,000 or makes 30 purchases a month. There is no charge to reload the card via direct deposit, but it can cost up to $4.95 to do so at a retailer.

The Fed, in granting a bank charter to Green Dot, has bestowed respectability on a form of financial player whom many have regarded as only one rung up from check-cashers and pawn shops. It is part of an effort, some analysts say, to bring financial services for

Though prepaid cards have been around for a decade, the explosion of their growth — and Green Dot's — can be traced to the economic downturn, rising consumer anger at banks and regulations that have

The rise of fees on once-free checking accounts and some banks' failed efforts to introduce debit card fees have led many in the prepaid industry now to argue that their cards are just as good a value — if not better — than the traditional checking account.

Streit is "in the right place at the right time when people are frustrated with their banks," says Kraft, a senior vice president at D.A. Davidson. "Banks are raising fees and they're pushing people out of the banking system."

Some critics say the Fed opened a Pandora's Box by allowing a prepaid card company to own a bank. But regulators put severe restrictions on the deal.

Green Dot has agreed to maintain a Tier 1 leverage ratio of 15% for five years, withhold dividend payments for three years and restrict ownership by any one entity to 10%. It also agreed to maintain cash equal to the new bank's insured deposits, which are generated from prepaid cards bought by consumers.

In approving Green Dot's bank application, the Fed also said it had "consulted" with Florida's Attorney General Pam Bondi, who launched an investigation in May into five prepaid card companies, including Green Dot, for possibly deceptive and unfair business practices. Green Dot has agreed to issue cards with "improved disclosures" that are "designed to address the matters raised by the Florida AG's office," the Fed said.

In addition to Green Dot the other companies

Streit says that prepaid "gets a bad rap and in many cases deservedly so because it started off being a shadow product." As Green Dot's customer base increased, the company took regulation and licensing "very seriously," he adds.

The company has no plans to offer any credit products or other lending-related features on cards issued out of its bank, he says.

Of the millions of prepaid cards issued, Streit claims Green Dot only receives a handful of complaints a year.

Some analysts have warned that prepaid card companies could

"Part of the Green Dot's reasons for purchasing a bank would be to counteract competitors lowering prices," says Leonard DeProspo, an analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott. "It helps them reduce costs a little bit and offers flexibility."

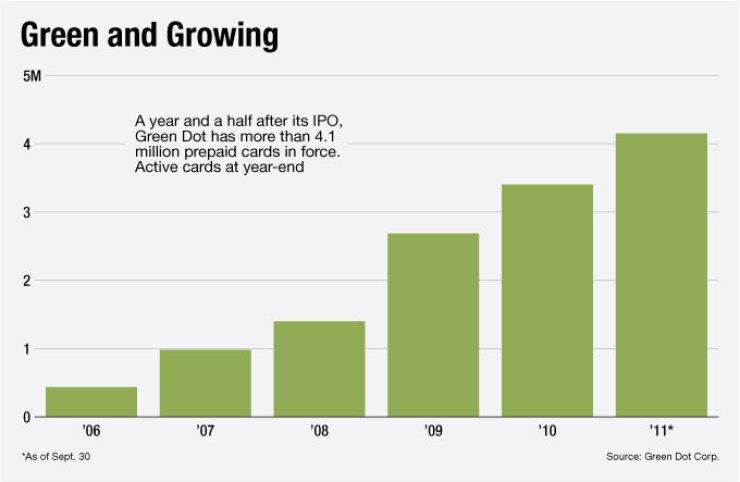

But the company still churns out some impressive financials. It had 4.2 million active cardholders in the third quarter, up 27% from a year earlier. Cash transfers rose 29% in the same period to 8.9 million. The amount of money loaded onto its cards increased 63% in the third quarter from a year earlier, to $4.1 billion.

All of that, plus the Fed's blessing, helps explain why Streit even manages to praise the lengthy bank-charter application process.

Regulators offer insight similar to what would be available from expensive consultants, he says: "It's as if McKinsey & Co. had come in," says Streit.

Getting approval to buy a bank was "a big deal," because now regulators "know what we're doing and why we're doing it and are supportive of that," Streit says. "It felt great knowing every corner of our business was looked at."