In an unpublished survey conducted this fall by Aite Group, a strong majority of credit union executives (75 percent of the 500 polled) indicated that online personal financial management tools for customers was a must-have investment either by this year or next.

But the enthusiasm shown by these credit union leaders-and by the bankers who have flocked to PFM providers like Yodlee, Geezeo and Intuit's FinanceWorks-has thus far not been matched by a similar response from customers.

This spring, research firm Celent reported that only 4 percent of online banking customers at the top 50 banks are active PFM users. And in a September survey of more than 1,100 U.S. consumers, Aite found that only 27 percent use PFM from any host, be it their own institution or a third-party site like Mint.com.

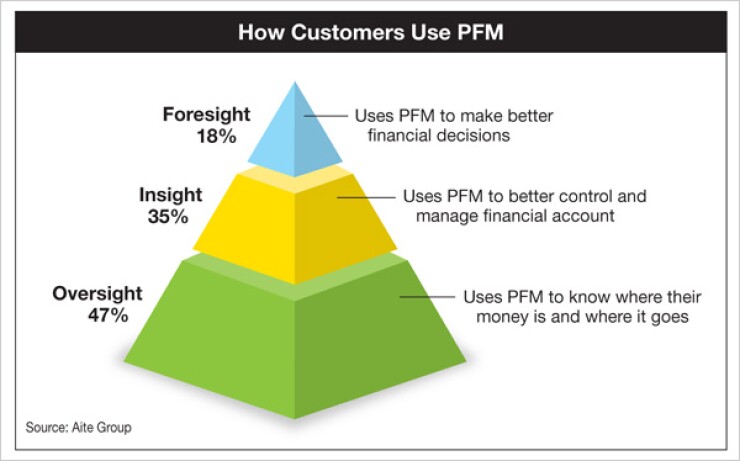

The problem, Aite research analyst Ron Shevlin says, is not a lack of promotion by banks to spark their customers' interest. Instead, it's a lack of recognition in the industry of what users want PFM to do for them.

"Why so few consumers use this tool is that so few are engaged or active in the management of their financial life," says Shevlin. "Eighty percent of people don't do budgeting. These are the people who aren't the Quicken junkies."

Shevlin is a frequent critic of banks' approach to PFM. At a September National Consumers League online panel with representatives of Mint.com, JPMorgan Chase and the U.S. Treasury Department, Shevlin pointed out 45 minutes into the discussion that none of them agreed on what aspects of financial management should be part of PFM offerings.

Are capabilities like budgeting and spending analysis enough? Or will PFM only gain traction when it becomes a factor in financial decision-making, through services such as real-time price comparisons or customized loan-rate appraisals?

Shevlin argued that without a true understanding of consumer needs, the whole premise that current PFM empowers consumers to "gain an understanding" of their fiscal lives is faulty. "I believe we have a PFM delusion problem in the financial services industry," Shevlin said.

Aite's survey shows a definitive lack of consumer interest in PFM: 58 percent have no plans to adopt it. Only 13 percent want their bank or credit union to help them with financial advice tools, and 46 percent don't care whether their institution offers PFM.

But for the small segment of customers who do use PFM, it's often a gateway to deeper relationships. The customers with the most comprehensive use of PFM-monthly spending forecasting, for example, have higher levels of new-account openings and referrals. Even the audience for a bank's social media outlets are almost exclusively those enrolled in PFM, according to Aite's survey.

Simply put, PFM works well to engage some customers, but it's just not useful enough in the ways necessary to attract the masses.

Where banks have missed an opportunity, Shevlin says, is in taking PFM into untapped areas of deep consumer interest. Tools like customized mortgage-rate evaluation technology from Credit Karma or Truaxis' handy tables comparing cell phone or cable TV service costs are options that, if part of a PFM platform, could make service enrollment not only more likely but potentially more profitable.

If banks can drum up enough interest, then perhaps they can offer a menu of PFM services they could charge for.

Some institutions are trying the fee-based model on for size. Portland, Ore.-based Unitus Community Credit Union, which offers a PFM tool called Total Finance on the Geezeo platform, charges $2 a month for a service that it promotes to wealthier customers who are apt to buy more products and financial advisory services. But the program, while robust, is still mainly about budget planning and expenditure tracking.

Geezeo's president and co-founder, Pete Glyman, says the company already is gearing up for next-generation PFM tools like mobile-based price comparisons or merchant-based rewards, delivered through spending data analysis that banks can compile from consumer activity.

"Rewards, merchant-specific information, offers, all of these things are building blocks," Glyman says. "But ultimately it's the data, it's the information provided through our system, that's going to empower a lot of these other value-added solutions."

Shevlin, too, believes PFM eventually will encompass features like rewards delivery, fraud protection and tools for smarter shopping, all of which can help banks push PFM program costs onto merchants. But that probably would require PFM providers to bring third-party developers onto their platforms, since it may be cost-prohibitive to develop a wide-ranging menu on their own. A model here is Yodlee's FinApp store, for which independent developers can create PFM tools (such as a tax preparation app) that banks can adopt and offer to customers.

To get there, though, banks first have to make a strategic shift in how they target PFM. Shevlin says the research shows that banks are too narrow in their focus in appealing only to a small segment.

"If you're looking to improve the relationship with the other 80 percent, then you've got to rethink what's going to be offered," he says. "It's a decision that banks have to make in terms of what's their strategy for PFM and how they define it in the first place."