-

It's a hot year for second-lien loans, which are already at $28 billion. But they may be "second" in name only for claims in the event of default because of the increasingly complex structures of debt issuances and inconsistent industry definitions.

November 26 -

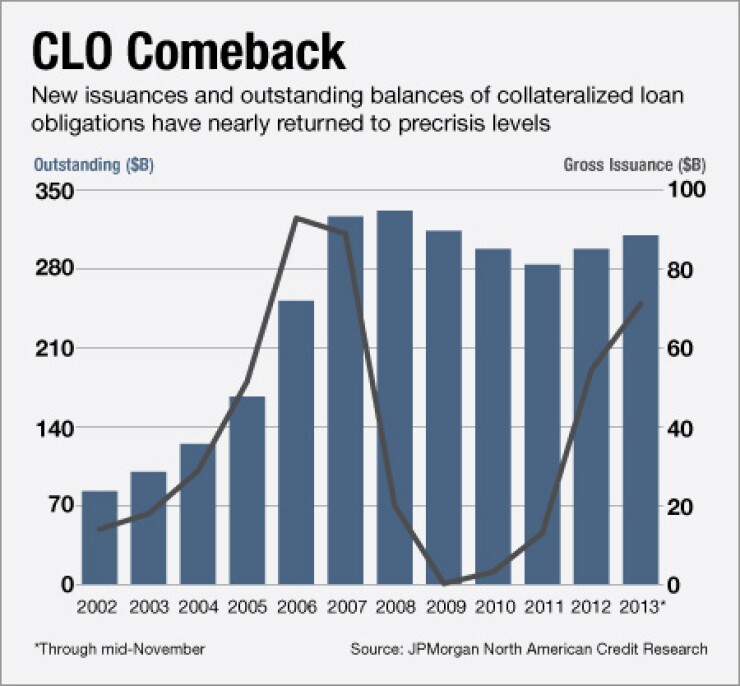

The surge in collateralized loan obligations, rising interest rates and other factors drove trading in leveraged loans to $391 billion at Sept. 30. The full-year total is expected to be a record, even as banks ease off CLOs.

November 18 -

A proposal that managers of collateralized loan obligations keep "skin in the game" could force them to shorten no-call periods on CLOs. An alternative would hurt banks that arrange these deals.

September 26 -

Banks bulked up on collateralized loan obligations again in the first quarter for risk management and other purposes. But new deposit insurance rules are expected to deter them from buying more.

June 17

The outsized sway of the collateralized loan obligation market's triple-A investor is no secret simple math will tell you that the relatively small group of investors buying up what is generally the largest tranche of a CLO transaction will have more power to dictate terms than would be the case if demand for triple-As were broader.

Interestingly, new regulations have driven some banks out of that group. The shrinking pool of buyers has heightened the influence of the remaining triple-A investors and makes it more likely that they will continue to wield this power over the growing CLO market.

Pet demands vary from investor to investor, market participants say. Maybe the buyer likes longer call protection, or has a lower tolerance for covenant-lite loans. A number of CLO transactions over the last several months have included a second triple-A tranche priced with a step-up coupon rate, meaning the yield increases in intervals over time.

This type of tranche has been customized for one particular triple-A buyer, which is trying to build a shorter-duration portfolio, market participants say. The step-up tranche typically can be refinanced at 1 1/2 years.

"The idea is that after 18 months the coupon steps up, and their hope is that the manager can refinance that tranche with another investor at a lower spread," said a banker at one of the market's lead CLO arrangers. "It provides incentive to make that bond shorter."

A recent example of a CLO with the step-up feature is a $609 million deal priced by Wells Fargo (WFC) in November for Apollo Credit Management. The deal included a $270 million triple-A tranche priced at Libor plus 145 basis points and a second $120 million triple-A tranche with an initial spread of Libor plus 110 basis points, according to a presale report by Fitch Ratings.

According to Fitch, the initial weighted average cost of funding for the second tranche is 1.86%; in July 2015 that increases to 1.98% due to the first spread step-up; it then increases again in July 2016 to 2.04% after the second step-up.

Likewise, a $415 million CLO priced in October by Wells Fargo for the Carlyle Group (CG) features similar pricing.

Carlyle's Global Market Strategies CLO 2013-4 has three classes rated 'AAA' by Moody's Investors Service. The $1.2 million in class X notes were marketed at Libor plus 90 basis points and the $122 million class A-1 notes were marketed at Libor plus 147 basis points. The $130 million class A-2 notes have a step-up coupon: they yield Libor plus 110 basis points for the first 18 months, Libor plus 160 basis points for the next 12 months and Libor plus 190 basis points thereafter, according to Moody's.

Additionally, American Capital CLO Management priced a $414 million CLO with a step-up coupon via Citigroup (NYSE:C) at the end of August. Again, the spread begins at Libor plus 110 basis points, then steps up to Libor plus 160 basis points at 1 1/2 years, and again to Libor plus 190 basis points at 2 1/2 years.

CLO arrangers and managers have long bemoaned the small pool of triple-A investors, which has remained insufficient to meet the strong demand for new-issue CLOs. More than 50 new triple-A investors have entered the market since 2011, according to some sources, but only a handful of them can take down majority positions of triple-A CLO notes.

"I feel that our job is to take feedback from investors on what they want and then find ways to create that product," said a second banker at another leading CLO arranger. "It may or may not be as obvious as a step-up coupon. There are other investors who might like to buy things at a bigger discount or they like a longer call protection than is normally there in a deal. What we try and do is find situations where equity investors and mezzanine investors are comfortable with that. So I feel that that's an ongoing exercise where people in our seats are getting feedback from investors on what they want and are creating product to cater to that."

That said, with less demand and widening spreads (CLO triple-A spreads were as low as Libor plus 110 basis points in the first half of the year, and by late November were around Libor plus 145 basis points), triple-A investors wield even more power at the negotiating table.

Part of the reason behind this trend is the

"If the depth of the market for triple-As were greater, if there were enough buyers to fully syndicate deals on a competitive basis and have oversubscription, then absolutely [they would have less power]," a CLO manager said. "But right now you've got a handful of people who can write really big tickets and a bunch of other people who can write smaller tickets. If you go to the guys that can write big tickets you're going to have to swallow their terms. The market's just not deep enough to drive competitiveness."

CLO issuance has increased significantly this year. Year-to-date global CLO volume totaled $85.7 billion via 180 deals as of Nov. 25, according to JPMorgan North American Credit Research. And available CLO supply continues to increase.

Carol J. Clouse is a freelancer based in New York.

This story originally appeared on