BB&T Corp.'s commercial finance unit has not gone prospecting for customers in nearly a month. It hasn't needed to.

The instability at CIT Group Inc., the 101-year-old commercial lender struggling to stay solvent, has generated a steady stream of incoming calls to BB&T Commercial Finance, at the rate of about 100 a week.

It is a similar story at Sterling National Bank and other firms with established factoring, accounts receivable management and other specialized lines of business for which CIT is known. Even banks without those specialties expect to see a pickup in their commercial portfolios as small and midsize businesses rethink their financing sources.

But, in a sign of the times, most lenders are taking a passive approach, avoiding a feeding frenzy as they try to balance a desire for growth with their desire to be prudent.

Banks that compete directly with CIT are being very choosy about selecting deals that meet their credit criteria, and taking a pass on the riskier bets that have contributed to CIT's woes. And lenders that have stuck to the more traditional aspects of small-business banking have expressed little interest in branching out, even if the opportunity to poach clients is palpable.

"In order to do this business, you need to know how to do this business," said Louis Cappelli, the chairman of Sterling National Bank, a subsidiary of New York-based Sterling Bancorp and the parent of Sterling Factors, a business with roots that date back 80 years. "You don't want to do on-the-job training because the risks are too high."

The sentiment may seem self-serving for an executive with so much to gain, but the notion is shared even by bankers with very little stake in businesses such as factoring — in which finance companies make loans backed by receivables or buy the invoices at a discount.

"I don't see this as being an opportunity for us to think about doing nontraditional lending but rather to stay very true to our roots," said Maria Veltre, the head of the small-business segment at Citigroup Inc.'s Citibank.

To the extent that Citi can capture CIT customers, Veltre said, she wants to be able to sell them a broad range of services such as cash management and payments processing, in order to build a relationship that goes beyond basic financing.

U.S. Bancorp chief financial Officer Andrew Cecere said that the less traditional aspects of small-business banking "would not be a priority" at his company, and James Rohr, the chairman and chief executive of PNC Financial Services Group Inc., reminded analysts last week that PNC has only a few areas of overlap with CIT.

"They do a number of things that we're not in, including factoring and some software financing … , [but] to the extent that they decide to reduce their balance sheet, I think there might be customer opportunities for us," Rohr said on PNC's second-quarter conference call.

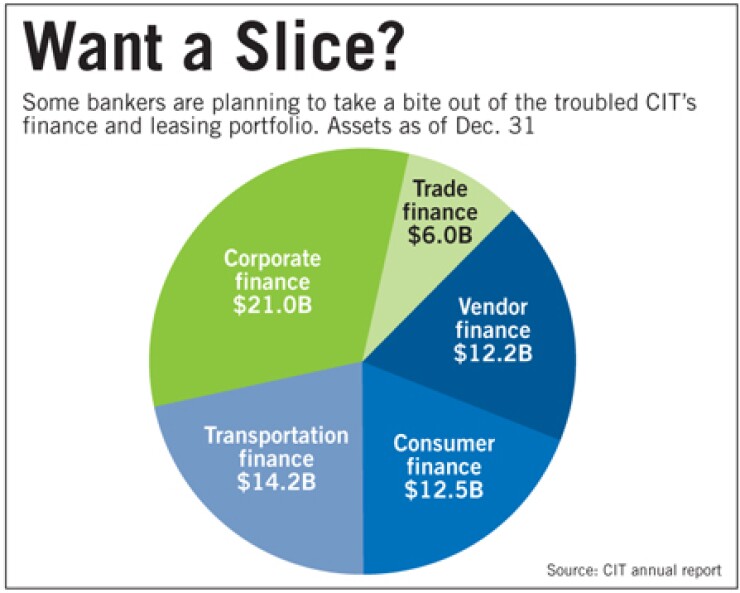

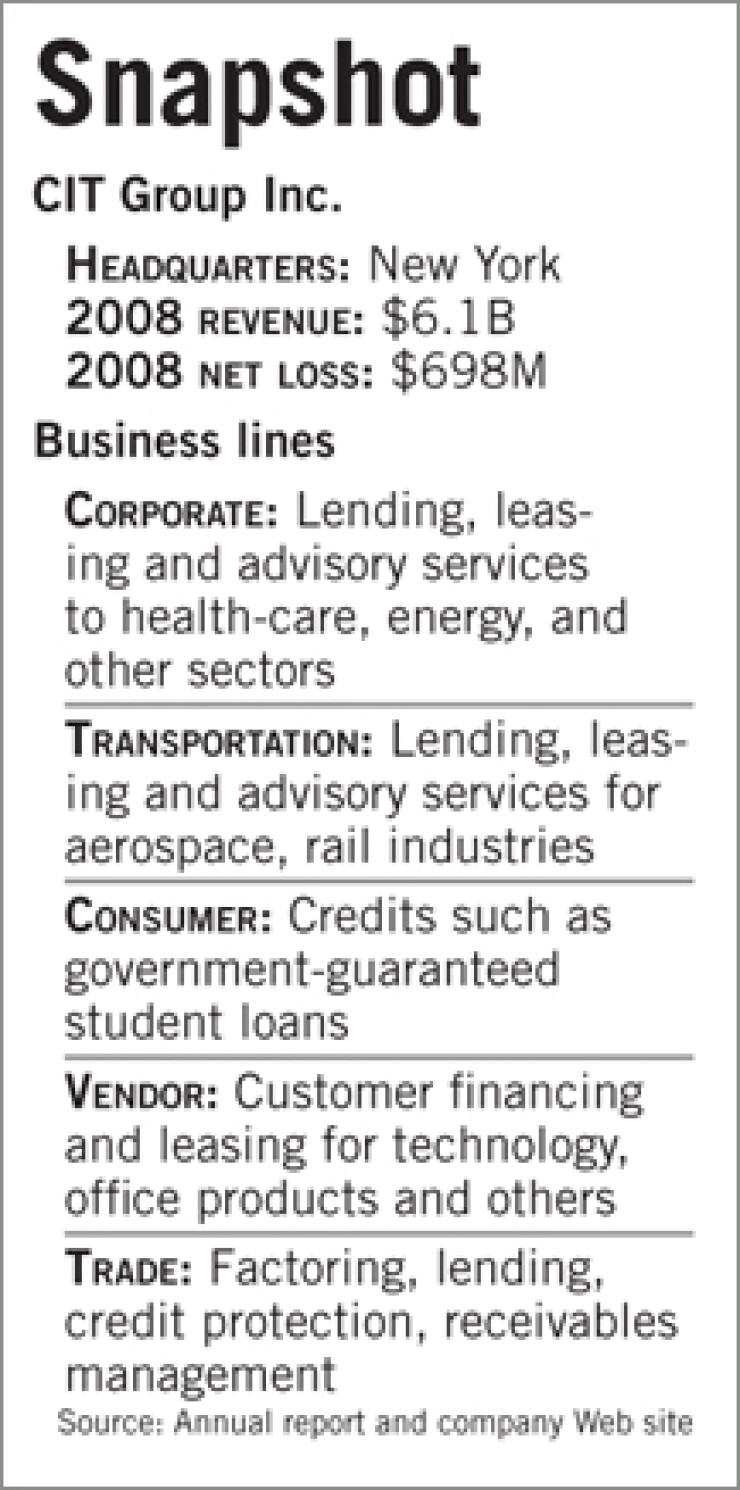

CIT supplies lending, leasing and financial advisory services to thousands of customers, with particular specialties in the health-care, energy, media, entertainment, aerospace and rail industries. Its other services include vendor financing, factoring, credit protection and receivables management.

Between its heavy reliance on the capital markets for funding and its extension of credit to businesses hit especially hard by the recession, the New York-based lender, spurned by federal officials who concluded the company did not fit the description "too big to fail," was forced to appeal to its bondholders to help ease a potentially devastating cash crunch.

CIT, which declined requests for a comment, has managed to stay afloat thus far, but the damage in some ways has already been done.

"It's difficult to do business with a finance company that's got its own struggles," said Darren Linder, the president and managing director of BB&T Commercial Finance. "I think [CIT's clients] realize they're in a precarious situation."

A similar, but smaller flight-to-quality scenario unfolded earlier this year as troubles at GMAC LLC sent some of its factoring clients into the arms of other finance companies. But some of CIT's clients may find a safe harbor difficult to find.

"CIT was willing to do deals that some of us in the market were not," said Linder, who likened its undercapitalized loans to equity investments that could never offer equity-style returns. "Usually whenever a vacuum is created, there is somebody willing to fill that gap. But it's not going to be BB&T."

This approach is prudent, given the times, said Rick Weiss, a bank analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott LLC in Philadelphia.

"There has to be some kind of opportunity, it stands to reason, if CIT is retrenching and everyone needs financing now. But at this point people are more worried about not losing money," Weiss said. "Bob Hope had that old joke, about how the bank is the one place that will lend you money only if you can prove you don't need it. I think that's where we are right now."

Of course, avoiding such deals is only one piece of a strategy for safely crossing the minefield of credit issues raised by CIT's woes. Banks also need to consider the exposures their own clients have, not only to CIT directly but also to businesses that depend on CIT for funding.

"There are several banks out there lending to clients based on the assigned credit balances from CIT, and that is a risk to the banks," Linder said. "If there were a bankruptcy, I don't think anyone could tell you what would happen to the credit balances CIT holds."