The way Dominik Mjartan sees it, a new building for the Midlands Arts Conservatory charter school will not only help a group of about 100 students, but could also give a distressed neighborhood in Columbia, S.C., an economic shot in the arm.

The $65 million-asset South Carolina Community Bank, where Mjartan is CEO, is strongly considering a $6.5 million construction loan to renovate a building for the school. None of it could happen, he said, without the promise of Opportunity Zone tax credits.

“This is a home run for the community because of the economic development benefits it would bring: Job creation, helping the students, bringing in new traffic and people spending money in the local community," Mjartan said. “This could be a model project for the Opportunity Zone program."

Many bank executives like Mjartan are enthusiastic about potential business opportunities created by Opportunity Zones, an element of the federal tax cut law that was enacted in December 2017. The Treasury Department issued initial

Banks expect to be involved primarily by making loans to developers backed by the investors. Some institutions, like PNC Financial Services Group in Pittsburgh, have already closed four loans tied to Opportunity Zone investments and has several more in the pipeline.

Many small banks are still studying how they can get involved, or if participation is even feasible. There are challenges, such as whether business loans will be eligible for a tax benefit. The guidelines also do not permit direct capital investments into community development financial institutions, which advocates say could be the most direct way to help low-income communities.

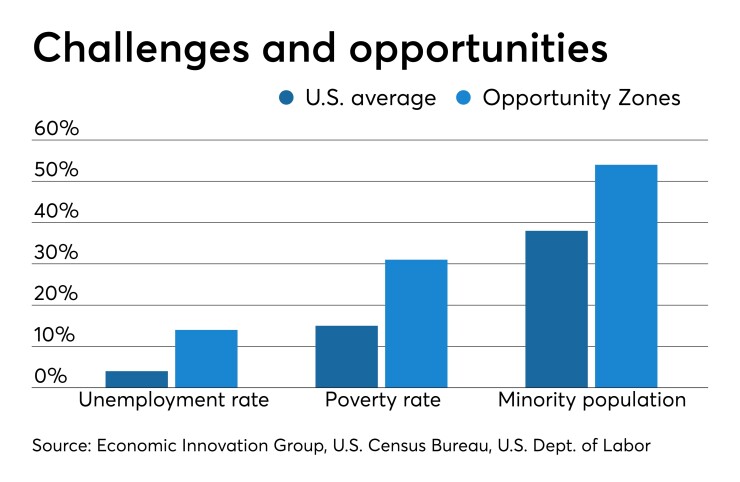

Still, the possibilities are enormous. Census tracts designated as Opportunity Zones have at least twice the national average of poverty and unemployment rates, according to the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington think tank. Minority groups make up more than half their population.

But the zones already contain more than 24 million jobs and 1.6 million places of business, according to EIG. That reality makes them fertile ground for private investment, said John Eliason, an attorney at Foley & Lardner who advises banks and private investors on tax issues.

“There is an estimated $6 trillion in investment opportunities that could be unlocked from this program," Eliason said.

Here is a closer look at how several banks are approaching potential new business opportunities created by Opportunity Zones, and at some of the issues and roadblocks that still remain for banks.

Pacesetter

PNC wasted no time in getting into the Opportunity Zone business.

Since the initial Treasury guidelines were issued in the fall, PNC has completed multifamily and economic development loans in Detroit; Philadelphia; Allentown, Pa.; and Wisconsin. And more are in the works, said Cathy Niederberger, managing director of community development banking.

“PNC really jumped out ahead of everybody else,” Eliason said.

The idea behind Opportunity Zones is to give a boost to economic development projects in economically distressed communities that might not otherwise qualify for financing. More

The expectation is that Opportunity Zones could help banks by creating a larger pool of commercial real estate loan opportunities, primarily construction and multifamily loans.

Banks can also establish investment funds to inject equity into these projects, although these funds thus far have been created primarily by private-equity groups or companies with a large real estate footprint, such as the

PNC has done both. It created a fund to make equity investments; the bank has not disclosed the size of the fund. And the bank is actively originating loans to serve as the subordinated debt piece of a larger equity investment.

The bank allocated $75 million for Opportunity Zone loans last year, Niederberger said. PNC declined to say how much it has allocated for 2019.

Many of the projects would not have been financially feasible for either the bank or the equity investor without the Opportunity Zone credit, Niederberger said.

But Opportunity Zones are not a cure-all.

“The Opportunity Zone credit is not going to make a bad deal any better,” Niederberger said. “Deals still have to have the fundamentals to economic sense. There are a lot of deals we see that have great social value that just aren’t ready.”

PNC fully expects to receive credit for Community Reinvestment Act compliance for its loans and investments, Niederberger said.

“We’re not the regulators, so they have the final verdict,” she said. “We believe that our investments (and loans) meet the need of community development under the CRA law.”

Niederberger said she was unaware if the

‘Everyone is trying to figure it out’

Many banks are actively exploring how to get involved, especially banks that already do work in low-income communities, said Jeannine Jacokes, CEO of the Community Development Bankers Association.

“Everyone is trying to figure it out,” Jacokes said.

A group of investors has identified a former apparel factory in Columbia as a great fit for the arts-centered charter school. South Carolina Community Bank, which is changing its name to Optus Bank, would provide more than half of the estimated $10 million needed to complete the rehabilitation.

“The work we do is a little more challenging,” Mjartan said. “We step into the void that traditional financial institutions can’t fill because it’s not part of their business model. Now here comes Opportunity Zones, which is a perfect alignment with our work.”

Opportunity Zone rules require equity investors to keep their money in the project for at least 10 years to receive the tax benefit. A lengthy minimum requirement should discourage private investors that are looking to make a quick buck and get out of town, said Tom Nida, market executive at the $366 million-asset City First Bank of D.C. in Washington.

But there is still a concern that a rapid influx of private capital could force some longtime residents to leave as housing becomes more expensive, Nida said.

“You may get a group of folks that do some investments, and it accelerates the gentrification, but they’re only focused on satisfying the investors’ interest,” he said. “We want to do projects that don’t displace a whole bunch of people.”

Some groups, including the National Association of Affordable Housing Lenders, have

But PNC’s Niederberger said affordable housing projects are well suited for Opportunity Zone financing. It can take a long time for a distressed neighborhood to rebound, which reduces the risk of an affordable housing development quickly becoming too expensive for local residents, she said.

“It takes a long time for neighborhoods to change their economic condition,” Niederberger said.

Questions of gentrification aside, Nida sees the role of City First as a matchmaker between investors who need money and developers who seek financing.

“I’m trying to put myself in the middle of this and get the right mix of players together,” he said.

City First has a couple of deals lined up, but the bank’s management is waiting on final details from Treasury before closing the loans. Many bankers and attorneys expect the guidelines to be issued by the end of next month.

Bill Dana, CEO at the $177 million-asset Central Bank of Kansas City in Missouri, is still trying to figure out his bank’s role. As a community development financial institution, Central Bank works primarily in low-income communities.

“The majority of the Opportunity Zones in Kansas City are right in the census tracts that we deal in and provide services to,” Dana said. “It seems natural for us to be at the table.”

Dana said he is continuing to examine possible business deals for his bank, but nothing has been finalized.

“We’re still trying to figure out the best methodology for deployment,” he said.

Issues on the table

Some questions may be answered in the upcoming Treasury guidelines. One question many bankers want answered is whether commercial and industrial loans will be eligible for the Opportunity Zones tax benefit, Jacokes said.

“Everyone seems to think that it’s only going to be big real estate projects that this will work for,” she said. “If you look at the places that need it, the intent of the Opportunity Zone legislation was to promote businesses and jobs.”

Some attorneys are optimistic C&I loans will be allowed.

“We take the view that this wasn’t intended to be solely a real estate pipeline,” said Mike Crossen, a corporate attorney at Foley & Lardner. “If it ends up being only real estate, it will be a lost opportunity.”

Jacokes also would like for Treasury to allow private investors to put equity directly into CDFI-designated banks for Opportunity Zone tax benefits. The rules currently do not address that question.

“These banks already have long track records of working in these places,” she said. “That will get the money into the communities that really need it.”

Finally, Jacokes hopes that Treasury will require some level of public disclosure of financial details. As of now, it is impossible to know what is happening with Opportunity Zone projects, which makes it difficult for small banks to find models for how to participate, she said.

“Greater transparency will help so we can learn who’s doing what,” Jacokes said.

After these outstanding issues are addressed, many bankers expect a rush to close investments and loans as quickly as possible, to get the clock started on the 10-year waiting period before withdrawals are allowed.

While it is a great idea to encourage private investment, one banker said he hopes that everyone will remember the reason for creating Opportunity Zones in the first place.

“The potential financial return over the long term is substantial,” said Adam Northup, senior vice president of strategy and finance at the $194 million-asset VCC Bank in Richmond, Va., which has already closed some Opportunity Zone loans. “The real challenge is delivering on the promise to revitalize low-income communities."