-

What initially appeared to be a listening session by a key federal regulator about access to checking accounts has sparked concerns that the agency may be seeking to go much further in dictating how and when banks open accounts for consumers.

October 27 -

Regions Financial in Birmingham, Ala., will stop using high-to-low reordering of checks and debits next year, resulting in a revenue loss of between $10 million and $15 million per quarter.

October 21 -

Banks that have been proactive in anticipating the regulatory winds might have little to fear from the rules, but others that have been slow to adapt could be forced to make significant changes that could crimp profits.

May 24

Regulators are turning up the heat on overdraft fees and, increasingly, so are banks.

Long a staple of banks' noninterest income, overdraft fees are more controversial than ever. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau on Monday gave strong indications that it

Banks are taking the hint. The $119 billion-asset Regions Financial, in Birmingham, Ala., last week announced that it is voluntarily making changes to its overdraft program that will

Regions is not alone. A number of bankers have delivered grim outlooks on the future of overdrafts during third-quarter earnings conference calls.

Jay Sidhu, chairman and chief executive at the $6.5 billion-asset Customers Bancorp in Wyomissing, Pa., offered perhaps the harshest take on the future of overdraft fees.

Sidhu decried the "nuisance fees that every single bank is charging the consumer sector," during an Oct. 21 conference call. "To give you an example, $32 billion in overdraft fees were charged by banks from consumers last year. On top of that, $7 billion in fees were paid by consumers to check-cashing companies."

"Well, that $39 billion, ladies and gentlemen, is three times what America spends on breast cancer and lung cancer combined," Sidhu said.

The future of consumer banking will involve the use of mobile apps to retain market share and drive interchange revenue, Sidhu said. His bank is

Most banks will soon be moving in the same direction as Customers and Regions, if they have not overhauled their overdraft fees already, said Nick Clements, co-founder of MagnifyMoney.com, a consumer website for comparing online and retail banking products.

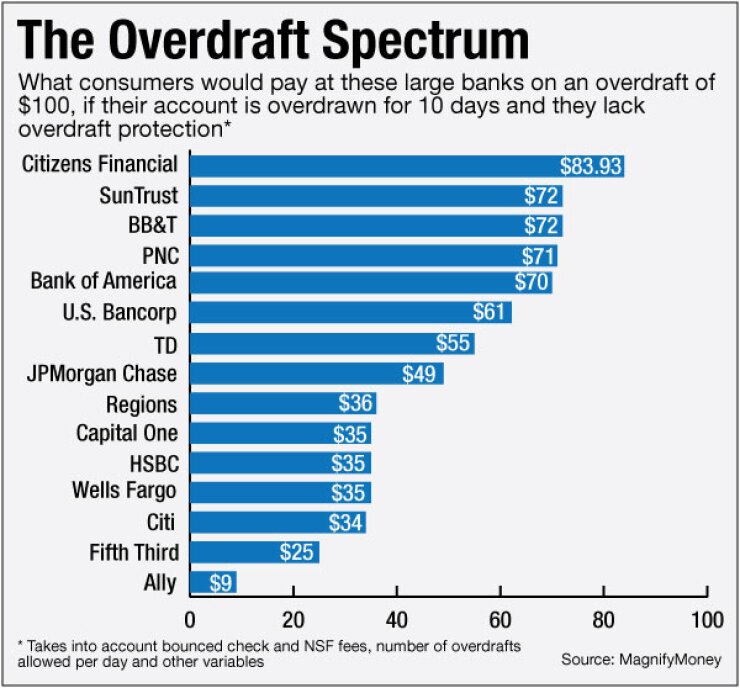

In a recent report conducted by MagnifyMoney.com, the $150 billion-asset Ally Financial was found to charge the lowest overdraft fees, among the 15 largest U.S. banks by assets, based on a hypothetical $100 overdraft with certain conditions. An Ally customer would pay $9 in overdraft fees, based on the example. (See related chart.)

By contrast, a customer of $131 billion-asset Citizens Bank in Providence, R.I., a unit of Citizens Financial Group, would pay $83.93 in overdraft fees, using the same example.

Ally Bank has already figured out how to make money in the new world of overdraft fees, said Clements, a former Barclays Bank executive. Citizens, as well as other banks that charge consumers high overdraft fees, are faced with making major overhauls to their business model.

"Ally is well-positioned," Clements said. On the other hand, "banks with the most aggressive per-day charges and extended overdraft fees, including Citizens, have the most to lose."

After Citizens Bank, according to the MagnifyMoney.com hypothetical example, the next-highest overdraft fees are charged by SunTrust Banks and BB&T, which each charge $72 per customer in overdraft fees.

The MagnifyMoney.com example includes numerous factors, which combine to boost the total fees at Citizens, SunTrust and BB&T, Clements said. Citizens, for example, charges an initial overdraft fee of $35, which is close to the industry standard. But Citizens also charges $6.99 per day, after the third day an overdraft is not repaid.

A Citizens customer, therefore, would be charged an initial $35 for the $100 overdraft. If the customer waits 10 days to repay the overdraft, he is charged $6.99 for seven days, for a total of $48.93. That results in total fees of $83.93 for the single $100 overdraft.

"Everyone focuses on the headline overdraft fee" of $35, Clements said. The "real money" comes from several other types of fees, like how many days a supplemental fee is charged.

A Citizens Bank spokesman responded that most of its customers use overdraft for four days or fewer, not the full 10 assumed in the MagnifyMoney.com scenario. The bank also offers a checking alternative that does not charge overdraft fees on debits of $5 or less, and no monthly maintenance fees if at least one deposit is made each statement period.

Assessing how much a bank generates from overdraft fee schedules is an inexact science. Banks are not required to break out the specific amounts of revenue they generate from overdraft. The figure is usually included with the noninterest income item "service charges on deposit accounts."

Making things more difficult, there is no uniform, industrywide standard for overdrafts. Some banks charge extended overdraft fees, while others do not. The maze of rules is difficult for customers to decipher, Clements said.

"The majority of [large] banks have confusing, fee-driven prices structures that are incredibly expensive" for the consumer, Clements said.

Other bankers have seen the writing on the wall and acknowledge that the heightened regulatory scrutiny of overdraft fees is going to force them to change the business models, if they haven't already.

"Probably one of the risks on the horizon for anybody who's heavily consumer-oriented is going to be overdraft income," Harris Simmons, the chairman and chief executive of $55 billion-asset Zions Bancorp., in Salt Lake City, said during an Oct. 20 conference call. "We are not trying to push that pedal any further. That's probably not going to be a growth area."

What's not hard to discern is the CFPB's intentions. During an Oct. 8 forum, Richard Cordray, the agency's director, discussed financial institutions' use of credit scores to assess risk when opening a new customer account.

"Most banks and credit unions have overdraft policies that allow consumers to have negative balances," Cordray said at the forum. "So the screening system is used to determine how likely it is that the consumer will incur overdrafts and pay them back."

Cordray's remarks seemed to indicate that "overdraft is nothing but credit," Donald Lampe, an attorney at Morrison & Foerster who advises banks on regulatory issues, said in an interview.

Bankers have

Consumer advocacy groups, like Pew Charitable Trusts, have called on the CFPB to look at what overdraft policies cost banks and require that overdraft fees be proportional to a bank's actual costs.