WASHINGTON — Although the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision provided clarity on new international capital standards this weekend, the panel left some crucial questions unanswered, including how it plans to calculate certain requirements for the most systemically risky institutions.

The board of governors and heads of supervision, which oversee the Basel Committee, outlined a plan that would effectively raise common equity standards to 7% by 2019, but made it clear it is weighing extra requirements for the largest banks. Although it said it planned to use a combination of "capital surcharges, contingent capital and bail-in debt," the panel provided little to no guidance on how it will do so.

"I know what the rules say, but putting all of these pieces into a coherent, finished rule on which strategic planning is based remains difficult," said Karen Shaw Petrou, a partner at Federal Financial Analytics Inc. "The basic accord with the tangible and core capital and the relationship with Tier 2 are very clear. But the relationship of the basic framework to the countercyclical buffer, the loss-absorption charge and the systemic charge — let alone proposals for contingent and 'bail-in' capital — is at best uncertain."

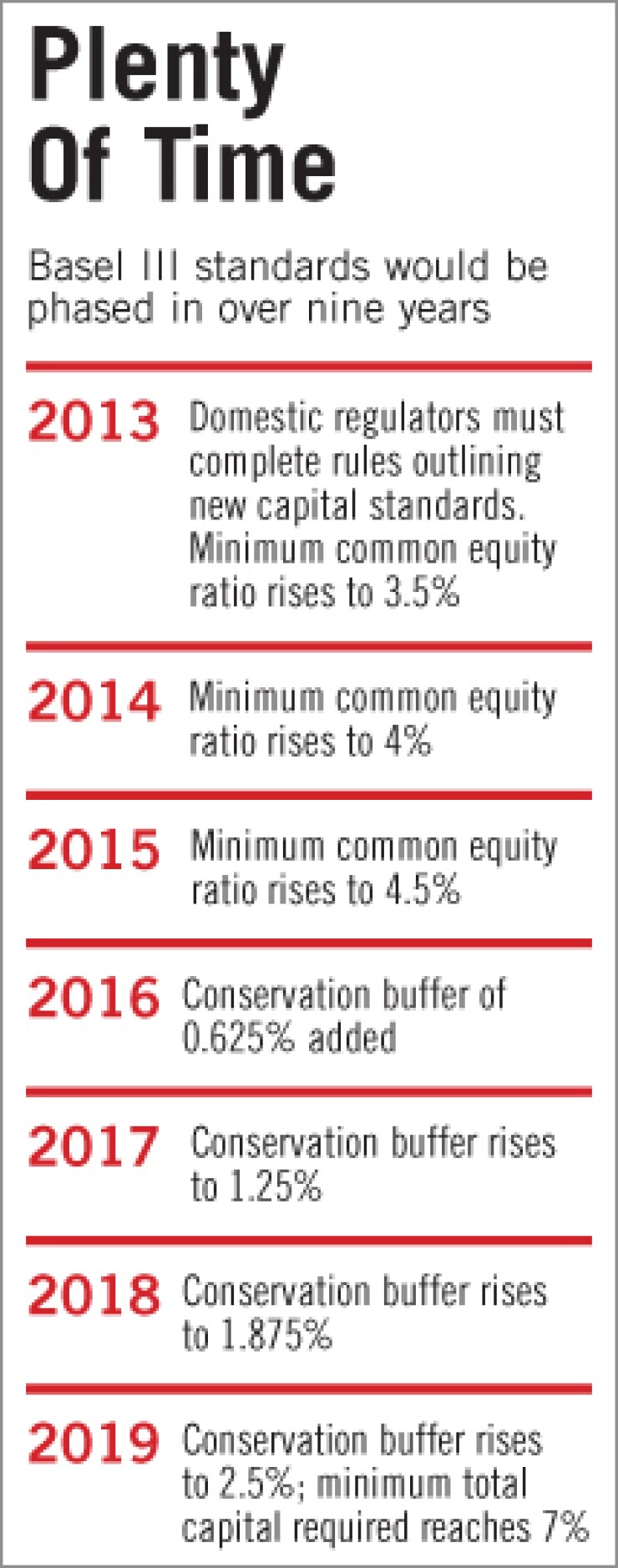

Others questioned the extended timetable for implementation of the Basel III standards. Capital requirements do not begin to go up until 2013, and then only gradually for the next six years. International regulators have made the case that a longer transition period gives banks additional room to shore up retained earnings or shrink assets to help minimize the impact of the changes.

But some observers questioned whether such an extended transition period would make the capital standards obsolete by the time they took effect. Basel II standards, for example, were considered significantly flawed as a result of the financial crisis by the time they were adopted. "It will take years for it to be fully implemented, so will the regulatory changes be obsolete because of yet-undetermined future events, or a future crisis?" said Cory Gunderson, managing director at the consulting firm Protiviti. "The longest transition provisions make it akin to being back in 1997 and looking forward. If we think about what the world looked like in 1997 compared to today, things have changed and are completely different."

The agreement announced Sunday was largely as expected, although the extended time frame was longer than anticipated because of concerns raised by some European countries.

But observers were left wondering what the future of additional prudential standards will be for the largest banks, with the Basel panel appearing to punt on the issue. "The Basel Committee release states that systemically important banks should have loss absorbing capacity beyond that set forth in the release, and the Basel Committee is working on an approach which could include capital surcharges, contingent capital and bail-in debt to create that additional capacity," said Greg Lyons, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton LLP.

While regulators have talked during the past year about contingent capital, a hybrid debt instrument that converts from debt to equity in a crisis, exactly how to enact it has been left unclear. Similarly, bail-in capital is another form of hybrid debt that is designed to raise equity under financial stress.

Regulators are also considering a surcharge on systemically important large institutions, but it is unknown if this will take the form of capital.

For their part, executives at large banks did not appear concerned.

"I am a strong supporter of strong capital standards," Brian Moynihan, the chief executive of Bank of America Corp., said during an investment conference Monday in San Francisco. "The new rules appear reasonable for economic stability."

Moynihan noted that the banking industry had already raised new capital and that the overall level of common equity is 50% higher than it was before the 2008 financial crisis.

"At Bank of America, we were at $60 billion in common equity before and now we're at $120 billion," he said. "The industry can weather a repeat of the last three years without raising new equity."

Howard Atkins, the chief financial officer of Wells Fargo & Co., said that his company would already be over the 7% minimum common equity ratio, before any deductions, and that regulators had struck the right balance.

"The regulators actually did a reasonably good job in reflecting the fact that different banks do have different risks, different risk profiles and different assets of different types of risks," he said.

Under the agreement, regulators said that banks should hold at least 4.5% of common equity by 2015, but added an additional 2.5% conservation buffer that goes into effect gradually by 2019. The Basel panel also raised the core Tier 1 level to 6% from 4% by 2015.

Importantly, however, regulators also left room for an additional capital charge that could come on top of all the other requirements. The Basel Committee said regulators could implement a countercyclical buffer between 0% and 2.5% for banks to build up capital during good economic times. But the panel left it unclear when or how that buffer would be phased in, leaving up implementation to "national circumstances."

Many observers said the panel's numbers are untested and it's unclear how the Basel Committee calculated them.

"One of the questions you have to ask is, how exactly did they come up with these numbers? It's not ground out in any quantitative analysis," said Kevin Jacques, Boynton D. Murch Chair in Finance at Baldwin-Wallace College. "What we would really like is some analysis that says this is the correct number of the amount capital that should be held."

The concern is that if financial institutions do not have a firm grasp of just much capital is being required, it's hard to tell what the implications could be for the entire banking system, or any potential unintended consequence on the macroeconomy.

"Regulators know they don't fully understand how the capital standards will affect the bank's balance sheet or the macroeconomy," Jacques said. "Because of the potential for unintended consequences they are giving themselves a longer time line to work these issues out."

Others said it was more important for the committee to provide numbers than to justify them.

"It's better to get those numbers and start dealing with them than going through months of additional uncertainty for an extra explanation," said Jaret Seiberg, an analyst for Washington Research Group.