There’s an abundance of capital available to finance lending to fix up or repurpose commercial property, and that has some people wondering how long the party will last.

More and more nonbank lenders are taking advantage of the strong appetite for short-term, floating-rate debt to bundle bridge loans into collateral for vehicles called commercial real estate collateralized loan obligations, or CRE CLOs. This funding is an attractive complement to bank lines of credit because it is matched term. And it is becoming less and less expensive.

“We have banks we’ve never done business with looking to extend us lines [of credit] in order to warehouse product for a CLO,” said Jeffrey Baevsky, a senior managing director in charge of structured finance at Greystone, which completed its first CRE CLO a year ago.

“Underwriters are calling us to push us to do another issuance, — they are being pulled by investors to find more product,” Baevsky said “We’re trying to take advantage of this situation. We see [the demand], we feel it.”

Greystone isn’t alone.

This once small corner of the commercial real estate market is growing rapidly. Through February, there were four deals totaling $2.3 billion, which is already about 30% of the volume for all of last year, according to Kroll Bond Rating Agency. In a March 6 report, Kroll said it expects to see six additional CRE CLOs announced over the next two months, several of which may be from new issuers.

“This is the most interest I’ve seen since 2005 or 2006,” said Jodi Schwimmer, a partner at the law firm ReedSmith who has represented investment banks, specialty lenders and real estate investors. “Deals are pricing well, and everyone [issuers] is trying to strike” while they can. “We’re advising clients to go to market now.”

As issuance picks up, the buyer base for CRE CLOs is expanding, creating a positive feedback loop for issuers as their funding costs continue to fall.

Take Arbor Realty Trust, one of the most regular issuers: The real estate investment trust saw a 63-basis-point decline in funding costs over the course of the three deals it completed in 2017, according to information posted on its website. The weighted average spread on all of the notes issued on the first deal, completed in April, was 199 points over one-month Libor. By comparison, the weighted average spread on the third deal, completed in December, was 136 basis points.

“This may be the most liquid and well-bid part of the [commercial mortgage-backed securities] market,” Kunal Singh, a managing director and head of U.S. CMBS capital markets at J.P. Morgan, said at a structured finance industry conference in February. J.P. Morgan underwrote nine of the 18 deals issued in 2017, and on average it placed 50%-60% of each deal with money managers, 20%-25% with banks, and 10%-15% with credit hedge funds, Singh said at one of the conference panels.

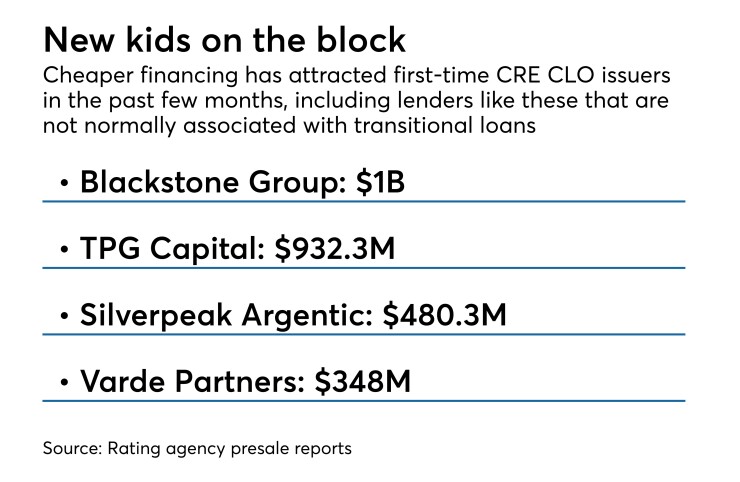

Most issuers of CRE CLOs are real estate investment trusts and other specialty lenders, but the cheaper funding is attracting some new issuers that are not necessarily associated with bridge lending, such as the private-equity and real estate giants Blackstone Group, TPG Capital, Värde Partners and Silverpeak Argentic.

Blackstone’s deal completed in

The $1 billion transaction was also roughly twice the size of most other recent CRE CLOs. Yet it was said to fetch top dollar.

Inevitably, people are starting to make comparisons to deals minted before the financial crisis, which were called CRE CDOs (for collateralized debt obligations) and were used to finance a much wider range of assets than first-lien commercial mortgages — including mezzanine debt, equity and even undeveloped land — and on much looser terms. These CRE CDOs were sometimes called “kitchen sink” deals.

Participants say the CRE CLO market is not there, at least not yet.

“Deals [today] are vastly different; frankly they are unrecognizable,” Gene Kilgore, executive vice president of structured securitization at Arbor, said at the February conference. Not only is the collateral higher quality, he said, but the capital structure of deals is much simpler. When Arbor returned to the CRE CLO market in 2012, it went out of its way to create a deal that even investors with little experience in the sector could quickly understand — and easily look through to the underlying real estate assets.

Arbor’s latest deals are “still fairly simple,” Kilgore said, though the sponsor has “added some bells and whistles to protect the investor.”

Baevsky also thinks the CRE CLO market bears little resemblance to its former self. “Before the financial crisis, deals, which were then called CDOs, financed office, retail, multifamily, land, hotels — you name the product, you could finance it there,” he said. “CDOs had 10-year terms, five years of reinvestment and 94% advance rates. Today’s world is completely different.”

Greystone is now looking to double origination volume for bridge and mezzanine loans, which was half a billion dollars in 2017, over the next year or two, and to add warehouse lines and possibly doing more CLOs. But Baevsky is not worried about having to compete for loans. Greystone's $9.5 billion in origination in 2017 is still a small share of the total multifamily and health care market, he said. “There’s a lot of turf left to capture.”

There’s no doubt that CRE CLO investors are getting comfortable with more kinds of collateral. While many of last year’s deals featured heavy exposure to

While this is a far cry from kitchen sink collateral, “we’ll get there,” Schwimmer said.

“Commercial real estate is doing really well right now … but you do feel there are clouds moving in,” she said. “How long can we go on like this? It [the length of the cycle] is unprecedented.”

New construction is also finding its way into CRE CLOs, according to Erin Stafford, a managing director at the rating agency DBRS. “We’ve seen that when banks can’t hold loans after construction, properties will come into CRE CLOs with zero cash flow,” Stafford said. “Banks don’t want to hold them for the stabilization period. We do see some more loans [in CRE CLOs] that need greater stabilization, typically a brand new property.”

Stafford says that this type of lending is here to stay, because banks cannot, for regulatory and cost-of-capital reasons, originate these loans. “What’s interesting to me is that banks are financing the CRE CLO sponsors” via lines of credit, she said. “It’s their way of participating in that market without directly lending [to property owners].”

At least one bank, Bancorp Bank of Delaware, is not only continuing to make bridge loans but also tap the securitization market for funding. Last week, it launched a $304 million offering of bonds backed by 30 commercial mortgages on its books.

As hot as bridge lending is, there could be even more room for it to grow if credit rating agency coverage of CRE CLOs expands. Currently, only one of the “big three,” Moody’s Investors Service, rates these vehicles. And Moody’s has only been rating the senior, or least risky, tranches of notes that are issued by each deal. Many large investors have investment guidelines that restrict them to purchasing securities that are rated by one or more of the big three (which in addition to Moody's includes S&P Global Rating and Fitch Ratings.) Issuers in other assets classes have found that getting rated by a second of the three boosts investor interest, lowering their funding costs.

“There are so many people in the bridge loan business, and a CLO is the perfect funding option,” said Joe Franzetti, senior vice president for capital markets at Berkadia Commercial Mortgage, a brokerage. “The question is, will people stick to their knitting? If they do reasonable bridge loans with first mortgages, we’ll be just fine."