"Deferred tax assets" may be the next accounting procedure to hurt banks' bottom lines — and force them to raise capital.

When banks are operating in the black, deferred tax assets accrued in the past offset current income, acting as a tax deduction to ultimately reduce taxes. Such assets are created when a bank's profit for financial accounting has been lower than the pretax income reported to the government. For example, loan-loss reserves or mark-to-market writedowns on securities hit earnings in the quarter taken, but do not affect pretax income because they are not reported to the Internal Revenue Service until the loss actually occurs.

Banks are allowed to utilize deferred tax assets to lower their taxes in future quarters, as long as they have pretax profits (and thus taxes) to reduce. Bank regulators however limit a bank applying the assets to two preceding years one year forward; banks for instance can use deferred tax assets to cover profits between 2007-09. If banks do not have enough of such profit in that period to cover their deferred tax assets, or are losing money, the bank may have to remove some of the deferred tax assets from the balance sheet. An expense item called a "valuation allowance" is then introduced onto a bank's balance sheet that cuts into whatever income there is, or accentuates losses, potentially leading to the need for more capital.

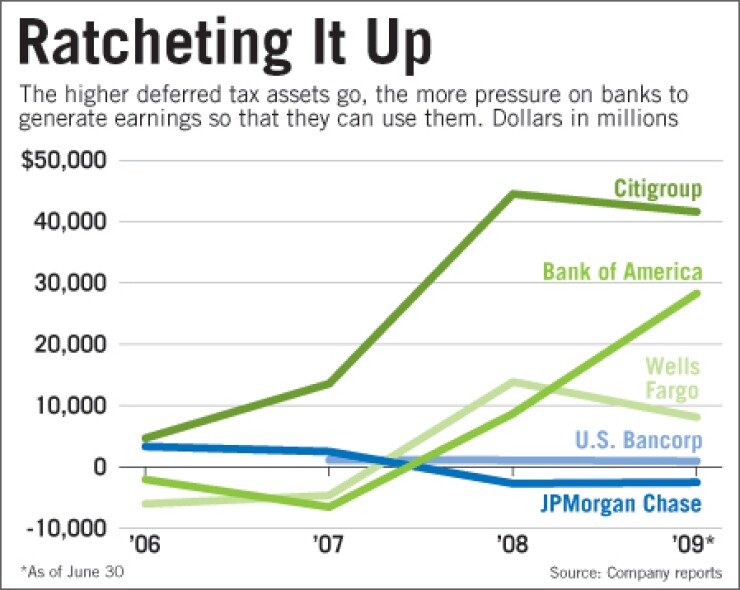

With banks' reserves and writedowns exploding, so, too, have their deferred tax assets.

Down the line, observers say, if banks do not start minting money, accounting for the assets could actually delay or reduce profits and cut into already tenuous capital levels.

"There will be some tough times ahead," said David Thornton, a partner at the accounting firm Crowe Horwath LLP. He said the level of deferred tax assets is significant, and some banking companies may be forced to raise more funds from investors "if the hit to capital is big enough."

Last year, deferred tax assets among the nation's 12 biggest banking companies totaled $71.3 billion, compared with $750 million a year earlier. Nine of those banks had deferred tax assets on their balance sheets in 2008, compared with five in 2007.

For the most part, bankers can do nothing independent of regulators or the IRS to soften an impending hit, sources said.

"If the standards are not relaxed … this would lead to an additional need for equity capital," said an accounting executive at a big banking company who asked not to be named.

Aaron James Deer, a managing director at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP, wrote in a note to clients last week that rising loan-loss reserves have played a major role in the growth of deferred tax assets.

Thornton, meanwhile, said the advent of fair market value also contributed to the spike in deferred tax assets, requiring banking companies to write down the value of certain securities even though a reported tax loss will not occur unless the holdings are sold.

Jack Ciesielski, the publisher of the newsletter The Analyst's Accounting Observer, said a surge in deferred tax assets paired with nominal profits or losses can have a detrimental impact on net income and capital.

Citigroup Inc. could face issues, some said.

The $1.8 trillion-asset company had the most deferred tax assets at yearend, with $44.5 billion. While Citi has posted two straight quarters of profits, they were preceded by five consecutive losses. (Citi's deferred tax assets fell 6.5% through mid-2009.) Having profitable quarters helps, but the company would still need to post significant earnings to erase the deferred tax assets that remain.

Bank of America Corp. said in a July regulatory filing that its deferred tax assets at June 30 more than tripled from six months earlier, to $28.3 billion, largely due to the $2.3 trillion-asset Charlotte company's purchase of Merrill Lynch & Co.

PNC Financial Services Group Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. also added deferred tax assets to their balance sheets last year after PNC bought National City Corp. and Wells Fargo acquired Wachovia Corp.

Wells Fargo said that essentially the company's profits are eating away at the deferred tax assets that they have accumulated.

Citi, B of A and PNC did not respond to e-mail requests for comment.

Sheryl Vander Baan, a partner at Crowe Horwath, said the stimulus package passed in February provided some relief by extending the look-back period to five years for small businesses with gross receipts below $15 million.

She estimated that the change only benefited banks with $100 million or less in assets, letting them match taxable income and deferred tax assets back to 2004. "Banks would be golden if they could all carry that look back further," she said.

Bank regulators also play a role in how deferred tax assets impact the bottom line and capital, sources said. Ciesielski said most companies are allowed to project their earnings streams out 20 years before determining the usefulness of deferred tax assets. "Most companies have a good long time to use them," he said.

The problem for banks is how regulators handle deferred tax assets, Vander Baan said. Banks can apply some of those assets to regulatory capital, but only the amount that covers pretax income in the two prior years and expected results a year out. "This could cause a big squeeze because something they had always counted on as regulatory capital may not be reliable anymore," she said. "We already have banks that have been required to take a haircut out of their capital levels."

The unnamed accounting executive said bankers are talking to the Fed and the IRS about ways to address the issue, including a plan that would extend the look forward to five years. "The proposed changes are under consideration but nothing definitive as of yet has come back from the regulators or the IRS," the executive said.