-

Sitting on a pile of cash from an initial public offering six years ago, NewAlliance Bancshares seemed poised to make a big acquisition. So it came as a surprise to many in the banking world Thursday when the company announced that it is being acquired by First Niagara Financial Group for $1.5 billion in a deal that would create one of the top 25 U.S.-based commercial banks.

August 19 -

One major question about First Niagara's deal to buy NewAlliance remains unanswered: what role Peyton Patterson, the seller's chief executive and one of the most prominent bankers in New England, will play in the post-merger company.

August 19 -

Chiefs of healthy community banks say they are talking more about doing deals with rivals hurt by the tepid economic recovery.

July 28 -

It was one of the busier weeks for dealmaking this side of the economic collapse. And though analysts say it might be too early to call it a breakthrough for open-bank deals, it is certainly a start.

July 16 -

First Niagara was arguably a beneficiary of the financial storm that had many banks over a barrel, making quick acquisitions that doubled its asset size from $9 billion to more than $20 billion and its shoe size from New York state to Pennsylvania, expanding from a community bank to a top 30 bank by market capitalization in about a year.

July 1

It's an important deal for sure. But calling it a game-changer for bank M&A might be premature.

First Niagara Financial Group Inc.'s agreement to pay $1.5 billion for NewAlliance Bancshares Inc. is the largest regular bank acquisition in two years. It sets a precedent for other lenders eager to grow by buying good companies, not failures. That makes it a banner transaction.

But it isn't likely to unleash a wave of pent-up deal activity because it indicates the market is only gelling for buyers and sellers that meet some rather stringent criteria, experts said.

Those include: Be somewhat small, profitable and on good terms with regulators. Don't have too many loan problems. Don't owe the government any bailout money. Operate in the Northeast. Being a serial acquirer helps, too.

First Niagara, of Buffalo, fits the profile, experts said. The $20.5 billion-asset institution returned its federal aid last year and is already one of the rare banks to buy a nonfailed bank since the start of the financial crisis. For its part, so had NewAlliance of New Haven. It has stayed profitable through the downturn, and it was one of the few lenders to actually expand its loan book last quarter.

The transaction — should it close next year as expected — would be a turning point for First Niagara by transforming it into a regional powerhouse in one of the most affluent regions of the country. Its impact on the broader mergers and acquisitions market, though influential, is not yet clear.

There just aren't enough parties that have the financial heft to buy another bank right now, according to William Schwartz, senior vice president of the ratings agency DBRS Inc. High unemployment, a stagnant economy and still-elevated loan losses mean that there aren't a whole lot of good banks worth buying at the moment either, he said.

"I don't know that we're going to see an avalanche of transactions," Schwartz said.

There are other limiting factors. Most of the banks healthy enough to buy are in the Northeast — as that region hasn't suffered as badly as other parts of the country during the recession.

And regular mergers are mostly feasible for banks with assets of $20 billion or less, Schwartz said. Most of the big regional banks are either bogged down with loan problems or still holding their federal bailout money, two characteristics that aren't conducive to doing a deal. The four largest banking companies — JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. Inc. — are off the deal market for a while as well. They're either committed to getting smaller or hold too many deposits, which restricts them from collecting any more through acquisitions.

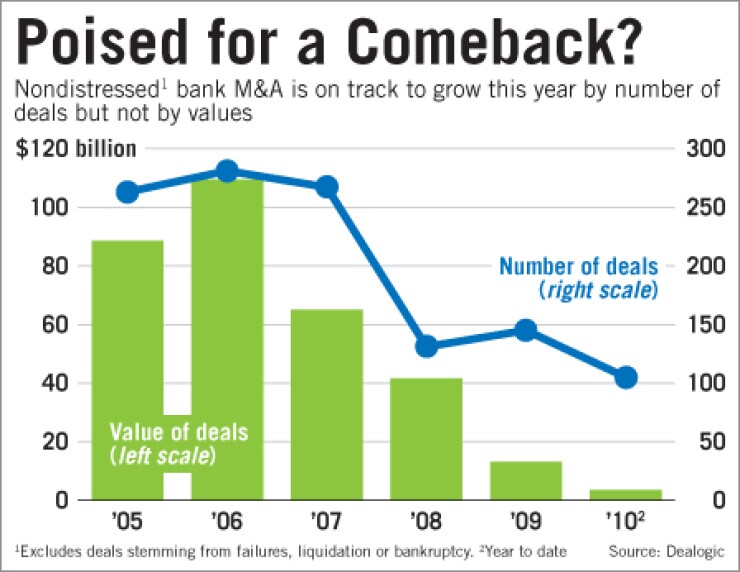

The First Niagara deal is still a significant development in the stagnant bank M&A market, which has been modestly rebounding this year after coming to a virtual standstill two years ago. It's not he first sign of life, either. There's another New England banking company that's been on the prowl for deals lately: People's United Financial. of Bridgeport, Conn. In July People's United said it agreed to pay some $156 million for struggling banks on Long Island and in Massachusetts.

The First Niagara deal is more important than that one, though, experts said. First of all, it is much bigger. It also ramps up pressure on Northeastern banks to start looking for deals now that they have to worry about getting outflanked by two big, insurgent players. Furthermore, it establishes a market price for a bank with 88 branches and $8.7 billion of assets.

It values NewAlliance at 163% of its price to tangible book value. Before the recession, banking companies were fetching 200% to 250% of their book value, according to Emmett Daly, a principal at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP and the lead advisor to First Niagara in the transaction.

He described deal values of 150% to 175% as the "new normal" for regular bank mergers. It could heat up the deal market in the region by shifting the competitive landscape and by showing that the banking industry is stabilizing, he said. "It will get the other banks thinking about where they stand in the pecking order — how they're going to compete and whether they can be a buyer or seller as well," Daly said.

It also helps establish a blueprint for structuring deals that makes sense for buyers and sellers, he said. A failure to see eye-to-eye on deal terms that are favorable to both is one of the reasons there haven't been more regular deals, Daly said.

The deal is 86% stock, which means that NewAlliance shareholders will walk away with a piece of a combined company that pays a higher dividend, he said. The $14.09-per-share sale price is also a "healthy" 24% premium over NewAlliance's closing share price Wednesday.

William W. Bouton — a partner with Hinckley Allen & Snyder LLP, the primary legal counsel to NewAlliance in the transaction — said lots of institutions have been talking more about doing deals.

Tougher new regulations will likely increase costs and cut revenue, he said. More banks are starting to question whether they can survive alone, he said.

But that doesn't mean there will be enough buyers lined up. Regulators won't be eager to let a healthy bank under its watch buy somebody else's problems, Bouton said. "I think you're going to have more interested sellers in the next couple of years than you had in the past," he said. "All buyers are going to be particular. It's not like the old days where you buy just to buy."