The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is set to unveil new details Thursday for how it plans to rein in debt collection practices, which would force banks to comply with new federal restrictions for the first time.

An outline of the plan, to be released at a public field hearing in Sacramento, Calif., is expected to address widespread problems in the $13.7 billion debt collection industry.

The plan could put an end to some of the most egregious debt collection practices, such as

-

The CFPB ordered New Jersey-based collection law firm Pressler and Pressler LLP and debt buyer New Century Financial Services Inc. to stop churning out collection lawsuits allegedly based on nonexistent or flimsy evidence.

April 25 -

CFPB Director Richard Cordray testified before a U.S. Senate committee Thursday and was questioned about the bureaus recent report stating service members complaints are nearly twice as likely to be about debt collection compared with the general population.

April 8 -

The FTC has published a reminder to debt collectors about Fair Debt Collection Practices Act compliance risks created by the use of social media or text messages in connection with debt collection efforts.

April 4 -

The CFPB's annual report to Congress updates the current status of proposed debt collection rules and lists four key themes that emerged from the more than 23,000 comments received after the CFPBs 2013 debt collection Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

March 28

Some in the industry welcome the changes as an opportunity to weed out bad actors.

"If the CFPB tries to address the real abuses in the industry, it could do a whole lot of good in this area," said Joe Lynyak, a partner at the law firm Dorsey & Whitney, who represents banks and servicers. "Setting down clear rules helps everybody."

Several banks and debt collection firms have already been forced to make changes. Some of the largest banks including

The two big publicly traded debt collection firms, Encore Capital Group in San Diego and Portfolio Recovery Associates in Norfolk, Va.,

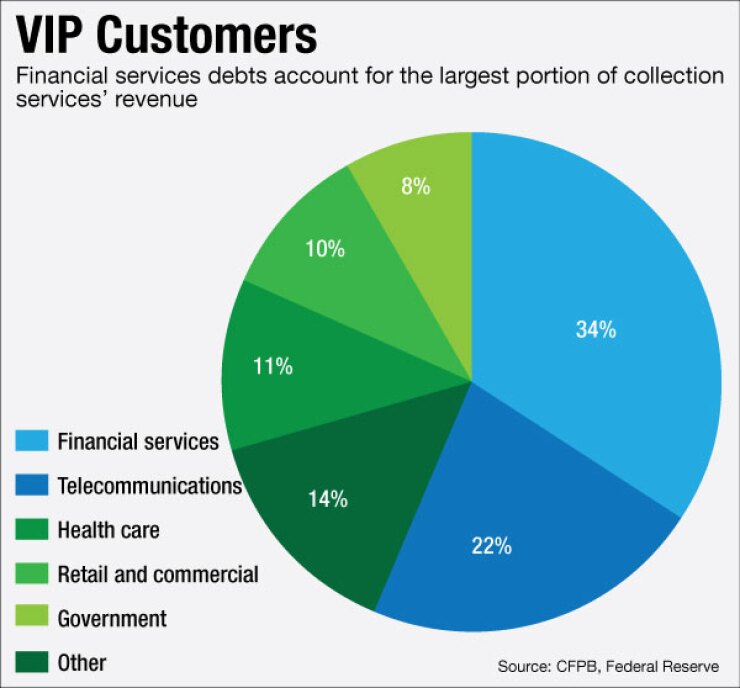

Underscoring how complex and far-reaching debt collection practices are, the CFPB said in March that it received 23,000 comments after an advance notice of proposed rulemaking in 2013. The plan would affect a wide range of industries, from payday to auto lenders, furniture dealers and cellphone companies.

By law, the CFPB must first outline its proposal to a small-business committee, which will study the plan and provide feedback, before formally proposing it. Here are five issues to watch when the CFPB releases its initial draft.

First Party vs. Third Party

The CFPB's proposal is expected to sweep banks and credit card companies under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, even though the law covers only third-party debt collectors. Banks and other first-party creditors that collect on their own debt have been exempt from the FDCPA since its enactment in 1977.

The big issue is whether the agency will update the rules governing FDCPA, or will instead use its authority under the Dodd-Frank Act to regulate unfair, deceptive or abusive acts or practices, known as UDAAP.

CFPB Director Richard Cordray wrote in an annual report to Congress in March that the agency was "considering provisions to ensure that debt collectors have sufficient information to collect the debt, prevent unfair, deceptive and abusive acts and practices, inform consumers of their rights, and provide interpretation of some sections of the FDCPA."

Jenny Lee, a partner at Dorsey & Whitney and a former CFPB enforcement attorney, said the bureau could write a debt collections regulation under the UDAAP provision as its standard for first-party collectors such as banks and installment lenders.

The distinction is important because financial firms that have long criticized UDAAP claims as ambiguous.

"This is pretty critical because the issue that recurs over and over with the CFPB is clarity and regulatory certainty," said Lee, who worked on some of the bureau's major debt collection enforcement investigations. "If there is not a clear standard, then it is very difficult to respond from a business perspective in managing compliance and litigation costs."

"Zombie Debt" Sales

In past enforcement actions, the CFPB has focused on the lack of data and wrong account information that creditors pass on to debt collection firms and debt buyers. Bad debts with inaccurate information often get sold over and over through repeated debt resales, a practice the CFPB has tried to rein in.

Last year, JPMorgan Chase agreed to a $216 million settlement for allegedly selling debts in which there was no documentation or the debt was already settled, had been discharged in court, or simply was not owed at all.

In that case, the CFPB relied in its enforcement action on the theory that JPMorgan substantially assisted third-party debt buyers. At the time, the CFPB warned others about selling "zombie debts" to third-party buyers.

Moreover, the Federal Trade Commission examined 5,000 debt portfolios purchased by the nation's largest debt buyers in 2013 and found that only 12% included documentation.

Statute of Limitations

How the CFPB treats so-called "time-barred" debt, which has exceeded the statute of limitations and therefore is not legally enforceable, is another area of concern. Statutes of limitations vary from state to state, and for different kinds of debt.

If the bureau requires disclosures to consumers about old debts, it may impact the ability of creditors to try to collect.

Roughly 77 million consumers, or 35% of Americans, have at least one debt in collections. Limits on collecting debts could potentially impact a portion of the $55 billion a year that collection agents recover, according to

Tom Scanlon, an attorney at Davis Wright Tremaine, said a requirement to provide notice to consumers would increase costs to banks and impact the market for aged debt.

"If the debt is not enforceable, should the consumer be asked to pay it or be advised about it?" Scanlon said. "A debt buyer would have to have increased sophistication and invest more resources to determine if the debt is enforceable."

Courts have ruled differently in this area. Some courts have said that threatening to sue to enforce a debt that has exceeded the statute of limitations is a violation of the FDCPA. Others have allowed debt collectors to ask a consumer to pay a time-barred debt, and if the consumer pays even part of it, the clock on the statute of limitations starts all over again.

"Some see this as an attempt by a collector to take advantage of consumer ignorance of the law," said Jeff Sovern, a professor at St. John's University School of Law, in an email response.

Joann Needleman, an attorney at Clark Hill in Philadelphia, said new disclosure requirements could upend the business models of many debt collection firms.

"If you tell a consumer that the [debt collector] doesn't have the right to sue you, what incentive does the consumer have to pay?" Needleman asked.

Registration System

The CFPB may also propose a registration system for debt collectors. Such a move would allow the bureau to more easily track officers and owners.

"Debt buyers and debt collectors notoriously reconstitute themselves into different types of legal entities," Scanlon said. "A system that requires officers and owners to register would allow the CFPB to keep track of managers and individuals running these companies."

Consumers have inundated the bureau with debt collection

The Tech Component

Technology is yet another major challenge for debt collectors given that FDCPA was enacted long before voicemail, texts or social media were used to collect debts.

Many industry observers are curious how the CFPB will deal with electronic communications.

"Is sending someone a 'friend' request when you are trying to collect a debt from them misleading?" asked Sovern.

The bureau is expected to clarify how debt collectors can communicate with consumers including parameters for email and text messages.

It's a new area. Last year, the Federal Trade Commission halted three debt collection operations that had threatened and deceived consumers through text messages in which they failed to identify themselves as debt collectors.

The CFPB's outline is a precursor to a formal proposal, which will be open for public comment. A final rule is not expected until at least the first half of 2017.