WASHINGTON — It has become a standard defense for industry representatives to claim a bill or regulation they oppose would result in the loss of credit to certain types of people.

But industry representatives and consumer groups agree a unique provision in a bill introduced by House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank will likely result in the loss of credit to some subprime borrowers — and that is what many lawmakers intend.

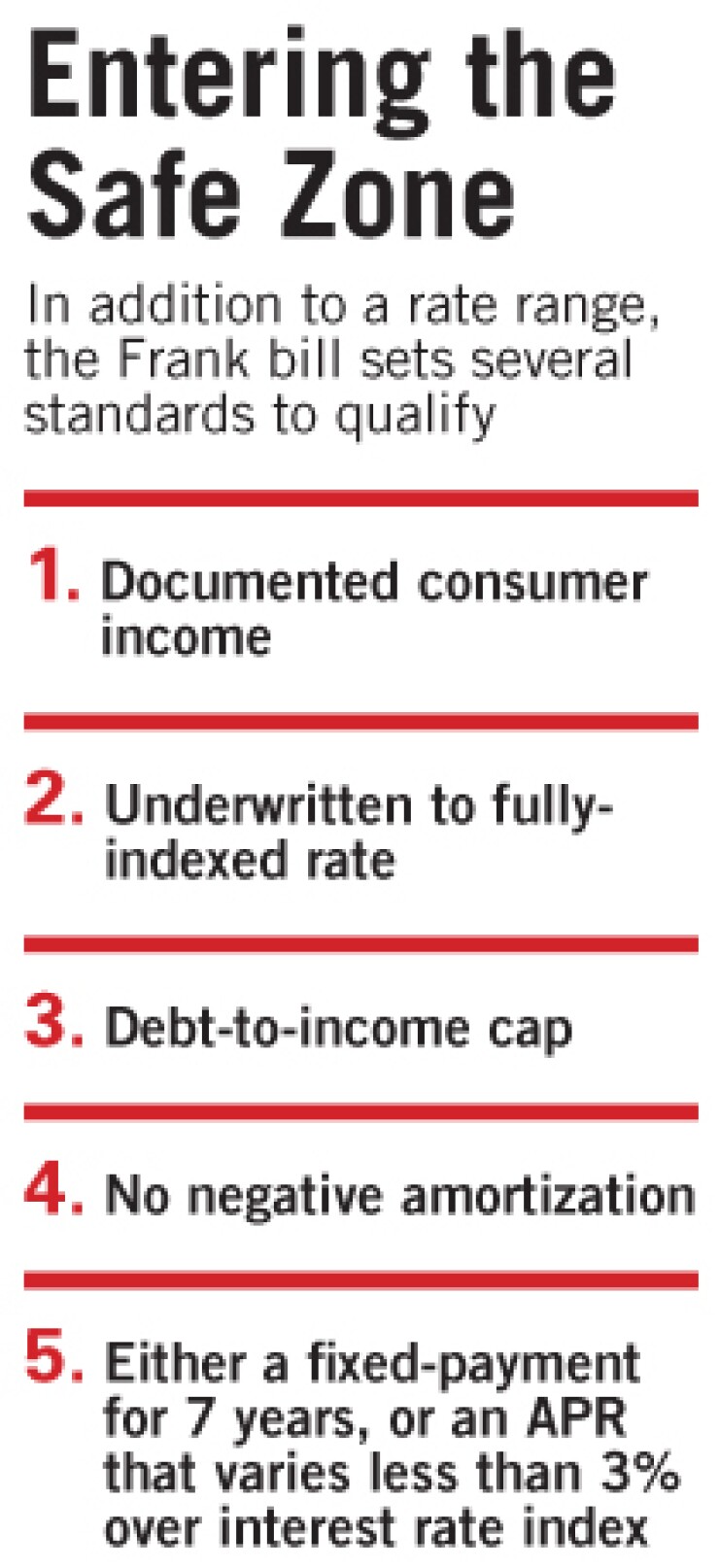

The provision at issue would exempt securitizers in the secondary market from any legal liability if the loan met certain criteria. The bill would protect most prime loans, which it designates as "qualified mortgages," but it also would provide a safe harbor for subprime and alternative-A loans that satisfy several individual tests, including verified borrower income, underwriting to the fully indexed rate, and a debt-income ratio of 50% or less.

Rep. Frank said the provision is necessary because lenders have made loans to those who should not have qualified for a mortgage.

"People should not be lent money that's beyond what they can be expected to pay back," he said in a call with reporters on Monday. "I know there are some who say we shouldn't touch the secondary market. The unregulated secondary mortgage market has been a major contributor to the biggest financial crisis in the world since the Asian crisis of the late 1990's, and the notion that nothing should be done to diminish the likelihood of the recurrence of that is quite wrong."

The safe harbor is designed "essentially to try to make sure that they are not selling mortgages that should not have been made in the first place," Rep. Frank said.

But industry representatives said they worry the provision may be going too far, and would quickly become the industry standard for all but portfolio lenders. Lenders would fear originating a loan that the secondary market is less likely to buy, they said.

"They are circumscribing lending that is acceptable, and while beyond that, at least theoretically, one could make loans, the absence of the safe harbor makes them problematic for most lenders," said Steve Zeisel, a senior counsel for the Consumer Bankers Association. "If that comfort zone is too small or isn't comfortable enough for the lenders or the assignees, it could have a restrictive effect on the availability of credit."

Since subprime mortgage credit has already tightened considerably, industry representatives argue the safe harbor should be expanded.

"There may not be much of a market for loans beyond the safe harbor for a period of time," said Scott Defife, the senior managing director of government affairs for the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. "We believe that there are legitimate loan products within the subprime area that should be covered in the safe harbor. We're still assessing what the effects would be on the subprime lending marketplace."

Industry representatives have long feared that some type of assignee liability would be added to subprime mortgage reform legislation. But lawmakers, regulators, and the Government Accountability Office blame the rise of the securitization model for helping fuel the origination of loans that were never designed to be kept on banks' books.

Rep. Frank's bill would provide a limited assignee liability by holding only the securitizer liable for the loan, as opposed to the investor who ultimately buys the mortgage. However, the securitizer would not be held liable if the loan were a "qualified mortgage," a category that covers most prime loans and is set by an annual percentage rate calculation tied to the yield on Treasury securities.

The second class of loans exempted from liability — "qualified safe harbor loans" — must meet other criteria, including income verification, underwriting at the fully indexed rate (including taxes and insurance), a debt-income ratio that does not exceed 50%, and a lack of negative amortization features. Additionally, the loans must include either a fixed payment of at least seven years or an interest rate that varies by less than 3 percentage points for adjustable-rate mortgages.

The industry is concerned about the provision partly because they have never faced anything like it before. "It's an unusual approach. The whole structure of the bill is different than the other models that have been around for a while for dealing with subprime or to address mortgage practices, so it sort of creates these categories of acceptable loans," Mr. Zeisel said.

Though the provision is limited, industry analysts said it is still likely to have broad consequences.

"The effect of having these safe harbors is that loans will only be made that meet these safe harbor provisions," said Beth DeSimone, a counsel at Arnold & Porter LLP.

"Just like how currently if something falls" under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act's provisions, "a lender will not make the loan, because they don't want to be saying they make high-cost loans," she said. "So they go to great lengths to avoid getting into that. … So they will only lend within the safe harbors, and I think that will decrease the availability of credit."

But consumer groups said that the only loss of credit would be for those who otherwise would receive a mortgage they could not afford — and that ultimately banks and other lenders will find ways to offer attractive products within the conditions and beyond.

"The access-to-credit issue is a red herring," said Alys Cohen, a staff attorney with the National Consumer Law Center. "There are very few people who will receive no loan because of the new rules, and for the most part people who receive unaffordable loans are in a worse position afterwards than they are before, because they lose all that equity in their home because of how foreclosure sales is done. It is not better to get an abusive loan and lose your home later."

Janis Bowdler, the senior housing policy analyst with the National Council of La Raza, said the financial services industry is making "really quite hilarious" arguments against the provision.

"We wouldn't want a bill that would infringe on the ability of families to buy a house," she said. "It seems to me to be a little bit of a farce to say that because you would do away with a certain kind of loan, which is risky and expensive for the family, that you will cut off access to credit for those families. You won't if lenders are willing to come to the table with responsible products."

Jim Vogel, the executive vice president of research with First Horizon National Corp.'s FTN Financial Securities Corp., said it is hard to gauge exactly what would happen if the provision became law, given how quickly the market is changing.

"The problem with all these kinds of discussions are that they are layered on top of the thought that the world that used to exist is going to continue to exist, and it's all just radically changed," Mr. Vogel said. "So now you are going to add a new set of regulations and thought processes on top of a world that's already undergoing significant change, so you know what you hope will be the outcome, but faced with increased uncertainty — who knows?"