During the last financial crisis, U.S. consumers proved surprisingly resilient in making their monthly car payments. Because so many Americans need vehicles to get to and from work, there was a certain logic in prioritizing automobile loans over mortgages.

This time may be different. With large parts of the economy shut down, unemployment claims are being filed at record rates. And for now, residents of 42 states are being instructed not to leave their homes unless it’s necessary.

The result is that coronavirus crisis is upending the auto industry. Lenders are offering forbearance at a previously unseen scale. Certain states have suspended repossessions. And with many showrooms closed temporarily, auto sales have fallen precipitously.

“There’s not going to be anybody out there buying cars in the next month or two,” said Mike Taiano, an analyst at Fitch Ratings. “And even beyond that, you wonder.”

As is true of so much right now, the ultimate extent of the economic damage will depend in large part on how quickly the spread of the virus can be controlled.

One bit of good news for auto lenders is that the Federal Reserve has taken steps to ensure that they continue to have liquidity. Under an emergency lending program that the central bank revived last month, securities backed by auto loans and leases are eligible as collateral.

Otherwise, the outlook for auto lenders is largely negative. What follows is a look at major ways in which the sector is being hurt by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Demand for new loans is cratering

In March, U.S. auto sales plunged to their lowest level in almost 10 years, according to Standard & Poor’s. Sales on a seasonally adjusted, annualized basis were 32% lower than in February.

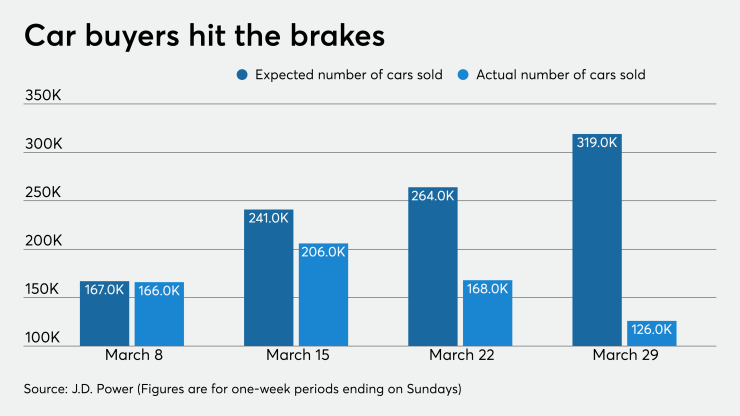

But the monthly data obscured an even sharper decline late last month. During the final week of March, retail auto sales were 61% lower than J.D. Power had projected before the coronavirus outbreak.

April figures to be an even worse month for auto sales than March was. In China, which experienced an outbreak of COVID-19 before the United States did, auto sales fell from over 2.5 million in January to fewer than 500,000 in February, according to the Center for Automotive Research.

Once U.S. states lift stay-at-home orders, the question becomes: How quickly does the economy bounce back?

“It’s not so much ‘How high does unemployment spike now?’ It’s really, ‘How long does it stay up at that level?’ ” said Warren Kornfeld, a senior vice president at Moody’s Investors Service.

Dealerships are on the ropes

The sharp decline in U.S. auto sales could spell trouble for many dealerships, some of which had substantial debt even before the pandemic. Lenders that provide consumer auto loans often have additional exposure to dealerships, financing both their inventory of automobiles and the upgrades they make to their buildings.

Steven Agran, an adviser to financially distressed companies, described the situation for many auto dealerships as dire. “It was tough in the best of times. And right now they’ve got no income,” he said.

Ally Financial, one of the nation’s largest auto lenders, said in a securities filing Wednesday that a significant number of dealerships that are Ally customers have enrolled in programs to defer loan payments.

Ally said that deferrals by both dealerships and consumers may negatively impact its financial results in the short term and potentially the longer term as well. The Detroit-based firm withdrew its financial outlook for 2020.

“You may see some dealerships that will flounder,” said James Houston, a senior director in the auto finance practice at J.D. Power.

One potential lifeline for vulnerable auto dealerships is the Paycheck Protection Program, the $349 billion initiative created last month by Congress to enable small businesses to pay their employees during the crisis.

But the program, which requires businesses to spend at least 75% of the funds on payroll in order to qualify for loan forgiveness, may not be a great fit for auto dealerships, since their employees typically earn a large percentage of their income from commissions.

Still, Bill Himpler, president and CEO of the American Financial Services Association, which represents auto lenders, warned not to bet against dealerships. “They have a way of making lemonade out of lemons in a way I’ve never seen,” Himpler said.

Consumer credit performance is poised to deteriorate

In a survey conducted by J.D. Power from April 3-5, 12% of consumers said that since the coronavirus crisis began, they have already been unable to make the minimum monthly payment on an auto loan.

Auto lenders are responding by offering forbearance — essentially an agreement to delay payments — on a scale never seen before.

While forbearance offers are common in the wake of natural disasters, those programs have previously been limited to particular geographic areas. The offers today are nationwide.

Ally said last month that its existing customers would be allowed to defer payments for up to 120 days. While no late fees will be assessed, finance charges will continue to accrue. Two other large auto lenders, Santander Consumer USA and Capital One Financial, are also deferring payments.

“Losses may actually be fairly low in the near term just because of the forbearance programs,” said Kevin Barker, an analyst at Piper Sandler. “To the extent this slowdown is shorter in duration, the better off we will be.”

The emergency legislation passed last month figures to help auto lenders in at least two ways. First, it provides payments to Americans that should help many borrowers stay current on their loans. And second, the law will allow lenders to defer payments without having to categorize the loans as troubled debt restructurings.

But analysts at Fitch warned that lenders will eventually have to pay a price.

“Once forbearance expires, Fitch believes credit performance for consumer finance companies could potentially deteriorate rapidly, particularly if displaced workers are unable to secure employment and businesses cannot resume operations once the economy reopens,” the Fitch analysts wrote on March 30.

Lenders that specialize in subprime auto finance face particularly big risks, since borrowers with marred credit typically have less ability to weather unexpected financial shocks. Late last month, Moody’s stated that it was placing 13 classes of bonds in 12 nonprime auto loan securitizations on review for possible downgrade.

“With any sort of credit cycle, I feel like you’re more exposed the lower down the credit spectrum you go,” Taiano said. “I don’t expect this to be any different.”

When loans do go bad, lenders will likely recover less money

Auto lenders typically rely on vehicle repossessions to limit their losses when customers stop paying their bills. But in recent weeks, Illinois, Maryland and Massachusetts have all put freezes on repossessions.

Other states, including Pennsylvania, are pressuring lenders to stop repossessing vehicles amid the nationwide health crisis. The result is that repo activity has declined, though to what extent is unclear.

Delays in recovering vehicles can cause them to fetch lower prices at auctions. And even apart from that dynamic, used-car prices are widely expected to fall in the coming months as a result of lower consumer demand. Falling used-car prices hurt companies that make auto loans because they figure to make smaller recoveries on loans that go bad. Lower prices are also bad for firms that offer auto leases, since they seek to sell vehicles when consumers’ leases expire.

Used-car prices, which increased by more than 50% since December 2008, are now expected to decline by 5% to 8% over the next two quarters, according to Moody’s Analytics.