Michael E. Kelly, the billionaire who built FBOP Corp. by snapping up ailing banks around the country in the 1980s and 1990s, now may have to give up some control of this far-flung empire — or lose all of it.

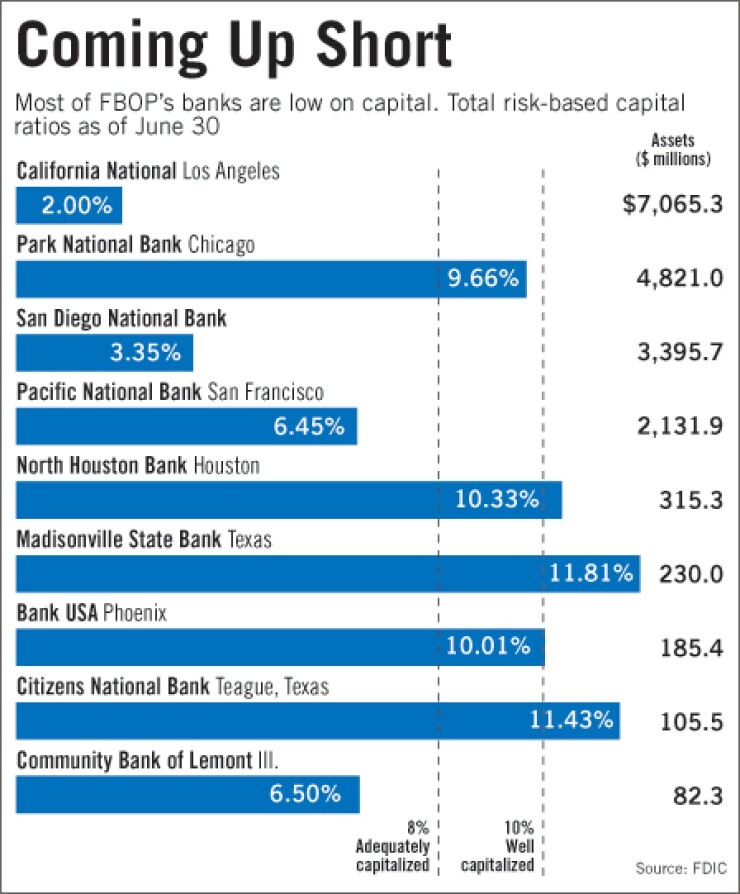

Four of the $18.3 billion-asset FBOP's nine banks, including the three largest ones, are undercapitalized. Regulators have ordered the Oak Park, Ill., company and one of the subsidiaries to submit plans to boost their capital ratios by the end of the month.

Kelly, FBOP's sole owner, has been reluctant to dilute his stake by selling shares in the company, but doing so may now be the company's last hope — if there are any willing buyers left.

"Right now it's a question of surviving," said Christopher Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners LLC. "The issue of giving up control kept FBOP from raising money." But "now it's a question of how much of the ownership of the company is he willing to give away to keep the company intact?"

Calls to Kelly and to Michael Dunning, FBOP's chief financial officer, were not returned.

Gregory A. Mitchell, the president and chief executive of the $7.06 billion-asset California National Bank in Los Angeles, FBOP's largest unit, said Tuesday that he "remains confident" his bank and the other subsidiaries will return to well-capitalized status by the end of the third quarter.

"We expect to have all the banks back to their capital levels by Sept. 30," Mitchell said. "All the banks continue to maintain solid core earnings and strong liquidity."

Mitchell would not say how FBOP plans to raise the capital. The company's troubles began a year ago when the government seized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, forcing hundreds of banks and thrifts to write down the value of their preferred shares in the two mortgage companies to virtually nothing.

FBOP was ensnared in that downdraft. It had to write down the value of its investment securities by $936 million, with a significant amount of the drop attributed to its stock in Fannie and Freddie.

The losses from Fannie and Freddie are believed to have scuttled FBOP's deal last year to buy PFF Bancorp Inc. of Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., for $30.5 million. (PFF later failed.)

Edward Carpenter, the chairman of Carpenter & Co., an Irvine, Calif., investment bank, said regulators may have given FBOP more time than other institutions to right itself because its initial losses came from investments in the government-sponsored enterprises, and because regulators have known Kelly for decades.

"Because the holding company lost money not on loans but on securities, they are likely to get more leeway than banks that lost money on problem loans," Carpenter said.

Marinac agreed that Kelly in particular has made a difference.

"Michael Kelly is more unique than other bankers because of his wealth and connections, and he might be able to pull off a transaction that is not available to everybody," he said. "They're giving him forbearance."

However, the ensuing year has led to further problems, mostly from commercial real estate and construction loans.

Both Cal National and San Diego National Bank had to take large provisions in the past six months based on low appraisals of underlying real estate.

In the first half of the year, FBOP wrote off $140.7 million in bad loans and provisioned $214 million for credit losses. As of June 30, it had $598.7 million of nonaccural loans or 4.06% of total loans, according to the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

Under a consent order issued in May, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency gave Cal National until Sept. 30 to submit a capital plan that would get its Tier 1 capital ratio to 7%, its Tier 1 risk-based capital ratio to 8% and its total risk-based capital ratio to 10%.

The OCC ordered the Los Angeles bank to submit a capital plan identifying the sources and timing of additional capital and methods for maintaining adequate loan-loss reserves.

On Monday the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago disclosed a similar order against the holding company with the same deadline.

In the first quarter, FBOP applied for about $500 million from the Treasury Department's Troubled Asset Relief Program. That was the maximum amount available to the company — 3% of risk-weighted assets — under program guidelines.

Marinac said the application might have succeeded if FBOP had tried to combine the proposed government infusion with a private one.

"Tarp was a game-changer for many banks," he said. But by now most of the companies with outstanding Tarp applications "have given up."

It is still possible for FBOP to do a "multiphase capital raise," he said, in which it would secure some of the needed money now to buy more time with regulators to get the rest.

Richard Levenson, the president of Western Financial Corp., an investment bank in San Diego, said Cal National's strategy has been "to effectively manage the loan portfolio" while the parent FBOP raised capital.

"The big question out there is whether the capital is actually available and whether it is willing to commit at this time," Levenson said.

"The vast majority of banks have been beaten up by this economic downturn and private equity isn't convinced we're at the bottom."

Potential acquirers might "wait and bid on the assets from the FDIC," he said.

There also is plenty of interest in FBOP's California operations with 113 branches at three banks spanning from the Mexican border to Napa Valley.

Should any of FBOP's subsidiary banks fail, the other banks could be stuck with the cost incurred by the deposit insurance fund.

While it has been rarely used, the FDIC has the authority to seize other affiliated banks as a way of mitigating the cost of a failure.

Experts said the likelihood of that power being exercised is increased if the remaining banks are healthy and the FDIC thinks it could get a good premium for them.

In July 1994 the FDIC seized Meriden Trust and Safe Deposit Co. in Connecticut to recoup the money it lost on the 1991 failure of Central Bank of Meriden, an affiliated institution. Both banks were owned by Cenvest Inc.

The FDIC sold Meriden Trust in October 1994 to People's Savings Bank of New Britain for $7.8 million, about 5% of the cost of Central Bank's failure.

Other examples of the cross-guaranty liability are less severe, with the surviving banks striking a deal to pay the FDIC.

"The FDIC is going to try to maximize their recovery" on any institution it seizes, said Walter G. Moeling 4th, a partner at the law firm Bryan Cave LLP, in an interview this summer. "It might be rare, but the cross-guaranty exposure is real and very dangerous."