-

The Department of Justice and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. have agreed to launch preliminary investigations into Operation Choke Point.

November 14 -

The California Republican, who's one of the most vocal critics of Operation Choke Point, trained his sights Thursday on Assistant Attorney General Stuart Delery.

July 17 -

Internal memos and emails show that the controversial probe was not exclusively focused on payday lending. At the same time, Justice officials did not think it was their problem if lawfully operating payday lenders lost their banking relationships as a result of the investigation.

May 30

Twenty-one months ago, the Justice Department launched an unprecedented investigation designed to enlist banks in law enforcement's fight against consumer scams.

The probe, colorfully named Operation Choke Point, was quickly embroiled in controversy. Its critics, chiefly financial industry lobbyists, payday lenders and congressional Republicans, cast it as a symbol of government overreach. They focused mostly on Choke Point's side effects specifically, whether it discouraged banks from doing business with lawfully operating but stigmatized industries, including state-licensed payday lenders, check cashers and ammunition dealers.

Lost in the ensuing hubbub has been any evaluation of whether the Justice Department accomplished its stated mission. Choke Point's architects set out to cut off fraudsters' access to consumers' bank accounts. And by all accounts, agency officials found success in the probe's early months, as banks jettisoned merchants that used business practices they would have a hard time defending. But more recently, Operation Choke Point has lost its momentum, according to both supporters and detractors of the probe.

After sending out more than 50 subpoenas early last year, the Justice Department has filed just one lawsuit against a bank. And the aftermath of that case, brought against the $837 million-asset Four Oaks Bank in North Carolina, illustrates that the Justice Department's most high-profile victory is not all that it was cracked up to be. Many of the online payday lenders that did business through the bank are still operating, according to a review conducted by American Banker.

Jeffrey Knowles, a lawyer at Venable who frequently represents financial institutions, questioned whether the probe has had any impact on the incidence of consumer fraud. "I'm not sure there's anything the government can point to," he said.

A consumer advocate who supports Operation Choke Point was more blunt."Obviously these problems aren't even close to solved," the advocate said, in reference to online payday lenders that operate without state licenses and are frequently accused of consumer abuses.

Emily Pierce, a Justice Department spokeswoman, urged patience regarding any assessment of Choke Point's effectiveness. "Complicated fraud schemes often take years to investigate and resolve. Our investigations are proceeding apace and we expect to make further public announcements in the coming year," she said in an email.

"No 'Whack-A-Mole'"

A November 2012 Justice Department memo that called for the establishment of Choke Point was sub-titled "A proposal to reduce dramatically mass market consumer fraud within 180 days."

The investigation was built on a simple theory: scams often rely on the criminal getting authorization to withdraw cash from a consumer's bank account, rather than waiting for the consumer to make a payment, so banks are well positioned to foil the schemes.

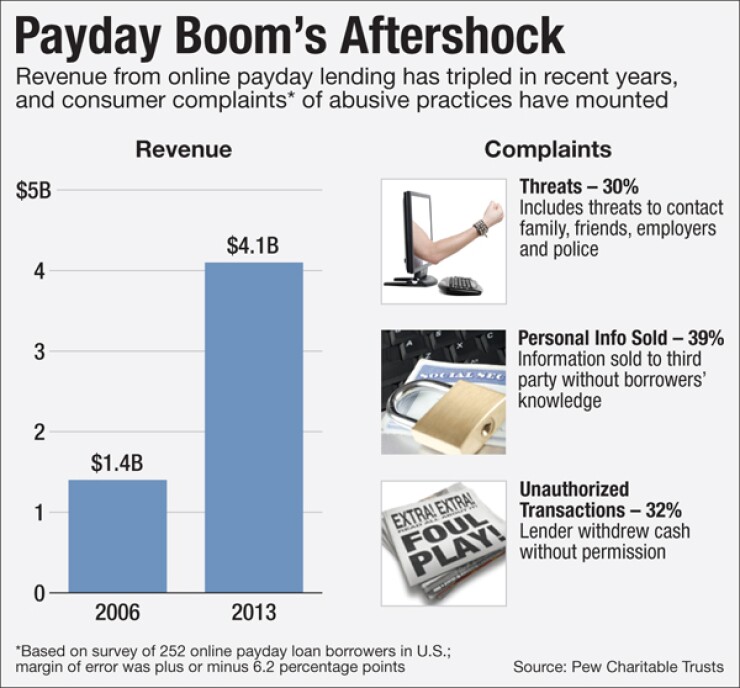

Online payday lenders, which have come into the crosshairs of Choke Point investigators, often persuade consumers to provide their bank account numbers and routing numbers.

Shortly after the borrower receives a paycheck, the lender uses the customer's bank account information to withdraw cash. Sometimes the amounts withdrawn

The Justice Department's focus on the banking system contrasts with the myriad state and federal law-enforcement initiatives that go after fraudsters directly, and are often stymied by shifting corporate structures, offshore addresses and other evasive maneuvers.

A department presentation from September 2013 suggested that banks were targets because they are regulated, concerned about their own reputations, and easy to locate. As the presentation put it, there is "no 'whack-a-mole.'"

The flurry of subpoenas that the Justice Department sent to banks and payment processors early last year, which was bolstered by numerous related actions at the state and federal levels, sent a message: continue doing business with questionable merchants at your own peril.

John Hecht, an analyst at Jefferies, said the Justice Department's probe had a clear impact on the online payday loan industry, which is made up of firms that operate with state licenses and others that do not.

Online payday loan volume fell sharply in the second half of 2013, he said: "The impact from Choke Point was fairly material."

Justice Department officials were pleased with the probe's early results. In a Sept. 9, 2013, memo, Michael Blume, director of the agency's consumer protection branch, wrote: "All signs indicate that Operation Choke Point is having an unprecedented effect on banks doing business with illicit third-party payment processors and fraudulent merchants."

In January 2014, the Justice Department

Notwithstanding the exceptional pressure on Four Oaks to reach a deal, financial industry lawyers expected the lawsuit's settlement to establish a template that the Justice Department would use quickly to craft numerous additional deals with other banks.

Instead, progress has stalled. Operation Choke Point has been hobbled by

What's more, many of the online payday lenders that once relied on Four Oaks Bank have found new ways to operate, casting doubt on the effectiveness of the Justice Department's strategy.

"Can I Have Your Social?"

The Justice Department's case against Four Oaks Bank was largely though not exclusively about Internet payday lending.

The complaint alleged that Four Oaks failed to do enough to vet online lenders that used a third-party payment processor to process electronic payments through the North Carolina bank.

None of the online payday lenders were named in the Justice Department's complaint against Four Oaks, so none of the companies were formally accused of fraud. But without identifying the lenders, the agency argued that many of them took unfair advantage of their customers.

The Justice Department's complaint identified certain red flags for online lenders, including a high number of customer complaints, a high rate of returned transactions and a failure to obtain state licenses. (

"Four Oaks Bank's own files contain many examples of how borrowers said they were deceived with respect to the design of certain Internet payday loans," the Justice Department's complaint alleges.

Later, in a related civil lawsuit, the names of dozens of online payday lenders that had relied on Four Oaks Bank were made public. And a review of that list by American Banker shows that despite the Justice Department's efforts, many of these online lenders are still in business.

Some of the firms are making loans without licenses from the states where their borrowers live, claiming immunity from state laws as a result of

"There's no doubt in my mind that unlicensed lenders that are charging hundreds of percent are knowingly breaking state law, and now, with the claim of sovereign immunity, are thumbing their noseat our entire government system," said Bruce Adams, general counsel in the Connecticut Department of Banking.

One of the companies that once relied on Four Oaks Bank is Island Finance LLC. The firm, which does business as White Hills Cash, offers loans with annual percentage rates of more than 600%, according to its website. It has been the subject of a consumer alert from the Washington State Department of Financial Institutions, which said it is not licensed to do business in the state.

Another lender on the list, Riverbend Finance, LLC, currently offers loans with APRs ranging from 520% to 782%, according to its website. A customer-service representative for the firm, which operates under the name Riverbend Cash, began a recent call by asking, "Can I have your Social?" in reference to the caller's Social Security number.

A third lender that formerly relied on Four Oaks Bank, Green Trust Cash, LLC, charges $1,162.50 in finance costs to repay a $300 installment loan, according to a customer contract from earlier this year.

That amounts to a 712% APR. When a caller recently asked what the interest rate is on Green Trust Cash loans, a customer-service representative replied: "As a first-time customer, the interest rate would be 30%."

As of July 2014, more than two months after a federal judge approved the Four Oaks Bank settlement, Green Trust Cash was processing customer payments through Lake City Bank in Warsaw, Ind., according to an email obtained by American Banker.

Mary Horan, director of public relations for Lake City Bank, said that Green Trust Cash is not a customer of the bank. She would not comment on whether Green Trust Cash is a client of a payment processor that is a Lake City customer.

"If they're being processed through a third party who was a customer, I wouldn't be able to talk to you about it," Horan said.

Green Trust Cash, Riverbend Finance and Island Finance are all Native American-owned businesses operating within the Fort Belknap reservation in Montana, according to their websites.

Supporters of tribal payday lending defend the business as a way to provide jobs on reservations that have sky-high rates of poverty and unemployment.

"We found something that actually makes money, and we're getting regulated out of business," said Michelle Fox, chief executive officer of the Island Mountain Development Group, an economic development corporation associated with the Fort Belknap tribe.

Fox acknowledged that online payday lenders associated with the Fort Belknap tribe have been able to stay in business, but said they continue to face pressure from both banks and regulators.

"Now we're trying to find new banking relationships," she said recently during a brief phone interview.

American Banker made phone calls to dozens of online payday lenders that previously relied on Four Oaks Bank, and found a mix of operating models, with some of the firms seemingly standing on firmer legal footing than others.

There were companies that appear to be based overseas, companies associated with numerous Native American tribes and companies that only make loans to borrowers in the states where they are licensed.

Some of the companies said that they are taking applications for new loans. Others said they are only doing business with existing customers.

Some of the lenders had Web addresses that are no longer working, and the firms could not be located. But that does not necessarily mean that the businesses have been shut down. It is not uncommon for operators of payday loan websites to adopt new corporate identities in order to fly under the radar of wary banks and law enforcement officials.

"Out of Sight, Out of Mind"

No matter how big an impact Operation Choke Point ultimately has, the government's fight against online payday lending will surely continue.

In one recent case, state prosecutors in Pennsylvania

Even in the absence of more lawsuits against banks, it is likely that the Justice Department is sharing with other prosecutors some of the information it gathered from Operation Choke Point subpoenas.

But the initial promise of Choke Point was something more substantial. The idea was that if every U.S. bank got on the same page, the banking system would become a solid bulwark against abusive merchants. That clearly has not happened.

A financial industry lawyer who asked not to be identified said that political blowback is one reason why Operation Choke Point has not yielded more results.

"I think it forced them to scramble internally, and to be very careful about how they're proceeding," he said.

This lawyer said that he is not ready to declare the Justice Department's investigation dead, but he added:

"Operation Choke Point was pretty dramatic when it first surfaced. After no one hears anything for a few months, it's kind of out of sight, out of mind."

Chris Cumming and Jackie Stewart contributed to this report.