-

A new report from Celent finds that many banks plan to expand their branch networks over the next few years even though all the evidence suggests that foot traffic is declining and that most transactions are now conducted online.

May 9 -

Avoid closing locations solely based on performance, test drive outreach programs and consider other options, such as amending hours, before shuttering an underperforming location.

April 16

Chris McLaughlin found a simple way to cut employee costs without closing a single bank branch.

Three years ago, McLaughlin, the director of retail banking at the $6.8 billion-asset First Bank in Clayton, Mo., began rejiggering the schedules of bank tellers to basically match their hours with actual customer traffic patterns. Since then, the bank has cut more than 120 full-time employees and changed 25% of the hours of bank tellers, reducing its personnel expenses by nearly $3 million a year.

It seems like a simple concept, but in reality many banks particularly smaller ones have no idea how many customers come into a branch in a given hour and how many transactions are actually processed by bank tellers. Technology has dramatically changed the way people bank, but many banks are

"It's all about linking the staff you need with the demands of the customer," says McLaughlin. "Banks are used to looking at deposits and loans, not production lines. We now have to balance how many workers we need on a production line and that's never been a core competency of bankers."

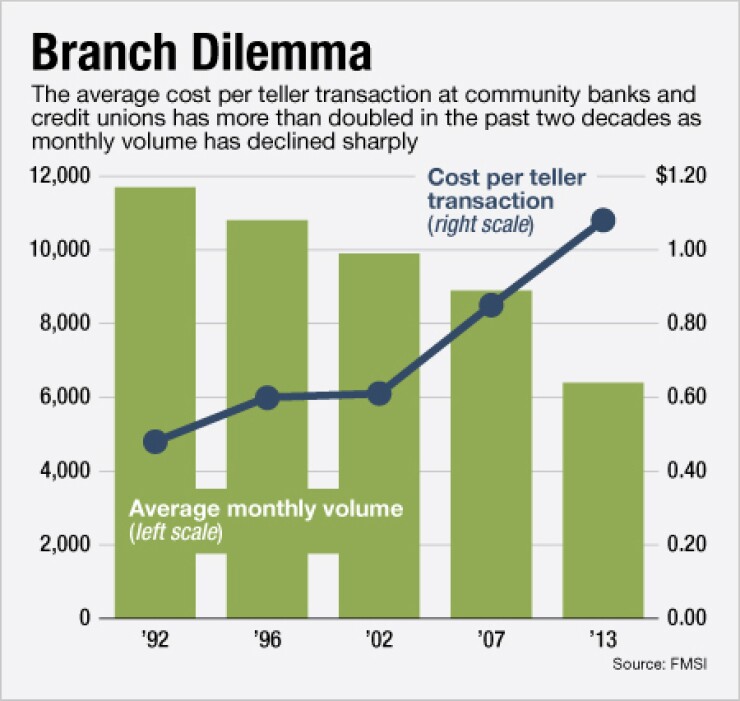

Bank tellers are processing 40% fewer transactions than they were 20 years ago, according to a new study by FMSI, largely because most routine transactions are now conducted online. At the same time, the labor cost per transaction has more than doubled because many banks have failed to adjust teller schedules accordingly, the study found.

Michael Scott, the president and chief executive of FMSI, says that most large banks have internal branch optimization teams, so his firm focuses on small banks that do not have the resources to track foot traffic and calculate transaction costs. According to the consulting firm Celent only about 3% of banks are addressing the issue of bank teller management, an "alarming" statistic, Scott says, given the importance of reducing overhead these days.

"Banks may not need to have long hours of operation on teller lines that they once did because of the diminished volume," Scott says. "There are huge operating efficiencies to be gained through better scheduling and hours of operation so a bank can downsize their staff to meet the volume."

FMSI works with 125 banks and credit unions to track the number of customers coming into any bank branch in 15-minute increments as well as the number of teller transactions in the same period.

Scott says that there usually is no need to have more than one bank teller working before 9:30 a.m. or 10 a.m., or after 3:30 p.m. to 4 p.m. Banks also can lower employee costs by identifying periods of down time and redirecting the teller to other tasks like sales though employees may not like the changes, Scott says.

JR Pimentel, vice president and human resources development officer at $1.3 billion-asset Bristol County Savings Bank in Taunton, Mass., says that getting data on branch traffic and tellers helped the bank reduce the scheduling of part-time employees.

"Even if we didn't need a part-timer on Tuesday and Wednesday, we would schedule those days to ensure they could work Saturday," Pimentel says. "Sometimes it can appear that banks are working for their tellers, not the other way around."

First Bank in Missouri continues to look for ways to improve efficiency in its 131 branches, but McLaughlin cautions that getting the data on branch traffic and teller transactions can be too much of a good thing because it might force bankers to "cut too much." Getting teller idle time down to zero can backfire if customers perceive they aren't getting good customer service. So he now aims for 20% teller down time.

Before First Bank began tracking the data on branch traffic and teller transactions about three years ago, it relied on estimates from bank managers many of whom were reluctant to cut staff.

"Unless you have the data you're basically trusting all the people who work for you and they always say they can't cut any more staff," says McLaughlin.

Still, there are some branches where some employees have been working for 15 years or more. Though the bank knew it had an opportunity to save money, it did not always make the changes out of loyalty to the staff.

The key is for the shifting hours to have as little impact as possible on customers, McLaughlin says.

"If I close the drive-up teller an hour earlier and not many transactions are affected, I can save on personnel expense," he says. "Evening hours, Saturday hours, how do you know if it's worth it? We're able to see so many hours on a Saturday and if a branch had less than 100 transactions, it was difficult to justify having the branch open on a Saturday.

We did some pretty significant changes to our hours and we have not heard a single complaint because we shut down branches when the customers were not there."

The $1.3 trillion-asset Extraco Banks in Waco, Texas, used FMSI data to create alternative delivery channels that it says are an extension of the traditional bank teller line. The bank uses video tellers to handle complex transactions and has three call centers that offer temporary backup support. It created a patent-pending methodology called Swarm Banking, whereby relationship bankers have replaced traditional tellers.

"We don't hire or have 'tellers' anymore," says Misti Mostiller, an Extraco executive vice president and director of retail sales, support and training.

Lindsay Green, director of marketing and business development for Extraco Consulting, a unit of Extraco Banks, says the 17-branch bank was able to cut between 1.5 to 3 full-time employees per branch over a three year period based just on bank teller data. Instead of laying off staff, the family-owned Extraco found other opportunities for employees within the community bank.

"We really tried to change from an order-taker mode to an advisor mode," says Green. "We're trying to look into the future and plan for two years from now when the business model changes."

First Bank also has experimented with having no tellers by moving to the universal banker model, in which anybody can do anything at every branch.

"You end up with the most experienced people facing off with the customer instead of what is normally the most junior," McLaughlin says. "Your costs per transaction go up but your overall costs go down."