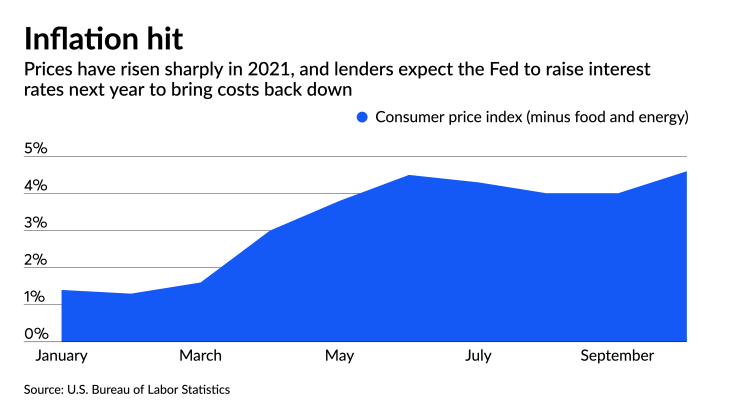

Any action to stem the rising tide of inflation could be good for lenders in the near term.

Janney Montgomery Scott analysts studied the last six periods of notable inflation — spikes in 1974, 1980-81, 1984 and 1990-91, as well as smaller increases in 2001 and 2008 — and found correlating increases in loan growth. Anytime inflation surges, policymakers at the Federal Reserve begin discussing higher interest rates to slow spending and curtail price increases.

When this happens, more consumers and businesses fast-track their borrowing plans to lock in loans before rates rise.

"Logically, it would make sense that the likelihood of higher rates would have an impact,” said Patrick Ryan, chairman and CEO of the $2.4 billion-asset First Bank in Hamilton, New Jersey.

“It’s no longer a question of whether this is a period of inflation; it’s a question of how bad it could get and how long it will last,” Ryan said in an interview. “I’m optimistic the Fed will move to keep it under control.”

He is among a growing number of bankers and analysts anticipating that inflation will spur an

U.S. inflation soared in October, reaching a more than three-decade high and

Economists attribute the change to the unleashing of pent-up consumer demand for goods — more than services — in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and ongoing supply shortages. With the holiday shopping season looming, Raymond James economists expect prices to remain elevated through the end of the year.

“Pressures were expected to be amplified by the fact that there was a lot to come back from, and speed of the recovery was especially brisk in the first half of the year following federal fiscal stimulus and the rapid arrival of vaccines,” said Scott Brown, chief economist at Raymond James.

That said, “the shift from consumer services to goods now appears to be a long-lasting phenomenon,” and supply chain issues are expected to continue into 2022, making it difficult to align supply with demand and curb inflation quickly, Brown said.

Higher interest rates are on the horizon as a result, according to Christopher McGratty, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. At the onset of the pandemic, the Fed pushed rates down near zero, where they've remained ever since.

KBW’s economic outlook incorporates an initial increase of 25 basis points in the federal funds rate in December 2022 and a second increase in mid-2023; however, “improving economic conditions and rising inflation expectations are leading some market participants to begin to price in both sooner and more frequent rate hikes,” McGratty said.

Loan demand is already rising. Forty-five percent of the banks covered by KBW produced at least 5% year-over-year core

The Red Bank, New Jersey-based OceanFirst Financial said loan demand is mounting, reflecting a strengthening economy and, likely, borrowers beginning to take action ahead of a year in which interest rates climb.

“I’m hopeful inflation is not a long-term issue,” said

Excluding PPP, he said the bank generated 7% annualized loan growth in the third quarter and anticipates it can maintain that rate. “We feel very bullish,” he said in an interview.

Matthew Reddin, chief banking officer at Simmons First National in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, echoed that sentiment.

Higher prices have benefited many corners of the economy, from

“We are definitely mindful of the challenges that inflation can cause,” Reddin said in an interview. “Nobody wants runaway prices.”

But he said the $23.2 billion-asset First National and most other banks are flush with deposits — a result of elevated saving amid the pandemic — and they welcome a bump in loan demand ahead of an eventual rise in rates so they can put those deposits to work.

“Everybody’s trying to put money into earning assets,” Reddin said.