-

On Tuesday, the $904 million-asset company said that Lee R. Keith, a director since 2009, as its interim president and chief executive. Keith succeeds Ted T. Awerkamp, who had served in those positions since 2007.

August 8 -

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. has ordered three community banks hobbled by losses on real estate loans to raise fresh capital or merge with other banks.

August 1 -

The Federal Reserve on Thursday announced written agreements with four banks, including the $2 billion-asset Old Second Bancorp Inc. in Aurora, Ill.

July 28 -

Unsuccessful in its efforts to raise fresh capital and already operating under multiple enforcement orders, embattled Mercantile Bancorp could be on the verge of failure.

April 25

Mercantile Bancorp Inc. once believed that its bank in sleepy Quincy, Ill. was not enough. Now, that bank might hold the key to the company's survival.

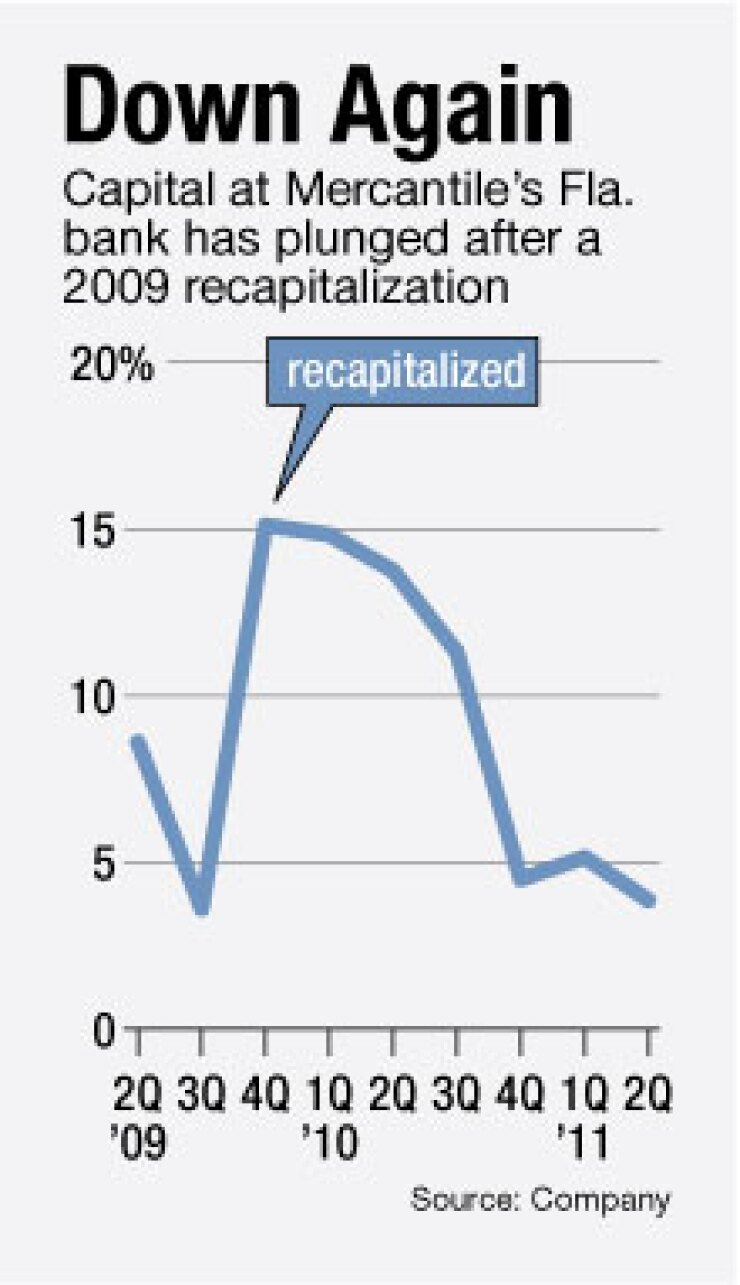

The $904 million-asset company is on the brink. Its Royal Palm Bank of Florida, recapitalized in late 2009, is once again significantly undercapitalized. Regulators have given that bank through the end of this month to boost capital.

Mercantile's Heartland Bank in Leawood, Kan., is also undercapitalized and the company itself is in a negative equity position.

The lone bright spot is its $663 million-asset Mercantile Bank. Though under some stress, the bank was well capitalized and profitable at June 30. Community bank experts say the company should sell its flagship bank to save the other two.

While Mercantile Bank is the company's core, there are no sacred cows in recapitalization scenarios, especially when an alternative is failure, industry observers say.

"They can't sell the whole company. No one would want to buy the other two banks, so they could try selling the lead bank. That would give the two terrible banks enough capital to move forward," said Michael Iannaccone, president of MDI Investments Inc., a Chicago-based community bank adviser. "It is not the best strategy, but what other options do they have?"

The danger embedded in Mercantile's situation is that failure of any bank unit has the potential of unraveling the entire company through the cross-guaranty liability, which gives the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. the ability to pin the cost of failure to any related banks. For instance, should Royal Palm fail, the FDIC can seize Mercantile Bank or Heartland Bank to offset the hit to the Deposit Insurance Fund through sales.

Like any failure, such a move would likely wipe out shareholders and put the board and executives at risk of litigation from the FDIC.

"I tell my clients that are in deep trouble to do any deal they can find. So long as it is approved, I tell them not worry about what they are going to get because no matter what they are going to be way better off," said Walter Moeling 4th, a partner at the Atlanta law firm Bryan Cave. "It is painful, but it is the reality."

Attempts to reach Lee R. Keith, a director who was named the company's interim president and chief executive last week, were unsuccessful. However, the company indicated its quarterly filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission on Monday that it is looking at a myriad of possibilities if it can't raise capital, including "selling or closing certain branches or subsidiary banks" and packaging and selling "high-quality commercial loans."

The company has already sold banks to rescue its troubled ones. In November 2009, it struck deals to sell three banks. In Illinois, it sold Brown County State Bank in Mount Sterling and Marine Bank and Trust in Carthage to United Community Bancorp Inc. in Chatham, for $25.6 million.

It also transferred its HNB National Bank in Hannibal, Mo., to R. Dean Phillips, its largest shareholder, in exchange for $28 million in debt forgiveness.

Mercantile's farflung network stems from a hunger to grow. The once $1.8 billion-asset company had plans of reaching $3 billion in assets, but didn't see that happening by remaining local.

"Our core, where we have established ourselves in the past 20 years, are solid markets, but they are not growth markets," said Ted T. Awerkamp, the company's former chief executive, in a 2006 interview with American Banker.

That year it closed on its $42.7 million purchase of the $147 million-asset Royal Palm Bancorp Inc., an expensive deal at the time that has given the company a lot of heartburn over the last few years.

"A number of banks were like these guys and thought, 'let's go where the magic is,' " Moeling said. "And it hurt a lot of people."

Analysts pegged the capital hole for Royal Palm and Heartland at roughly $25 million. Iannaccone said that Mercantile Bank could likely fetch a deal at or just less than its $48 million book value. Such a price tag should be sufficient to save the company and bail out the two struggling banks.

Moeling said that the regulators would have to be confident that the proceeds would be enough to fix the other banks before blessing any deal.

"The FDIC is looking for a complete fix," Moeling said. "And it is all in how the numbers add up."

Such a deal would leave a small company with two banks in very different markets, but those are tomorrow's problems, said Terry Keating, a managing director at Amherst Partners in Chicago.

"This is a desperate situation where failure might be inevitable, but they might have this creative solution in selling the largest bank," Keating said. "When you are in this position, it is not a strategic play to thrive, it is a play to minimize the damage."