For banks that built up significant portfolios in the municipal interest rate swap business, it may be time to consider what to do when the customer isn't always right.

On Friday the Los Angeles City Council directed the city to ask the holders of two $158 million swaps to ease the terms of deals that one official pronounced a "rip-off." The measure followed advocacy by the Service Employees International Union, which has seized upon the cost of exiting swaps as a central point in a nationwide effort to blame banks for heavily indebted municipalities' service cuts.

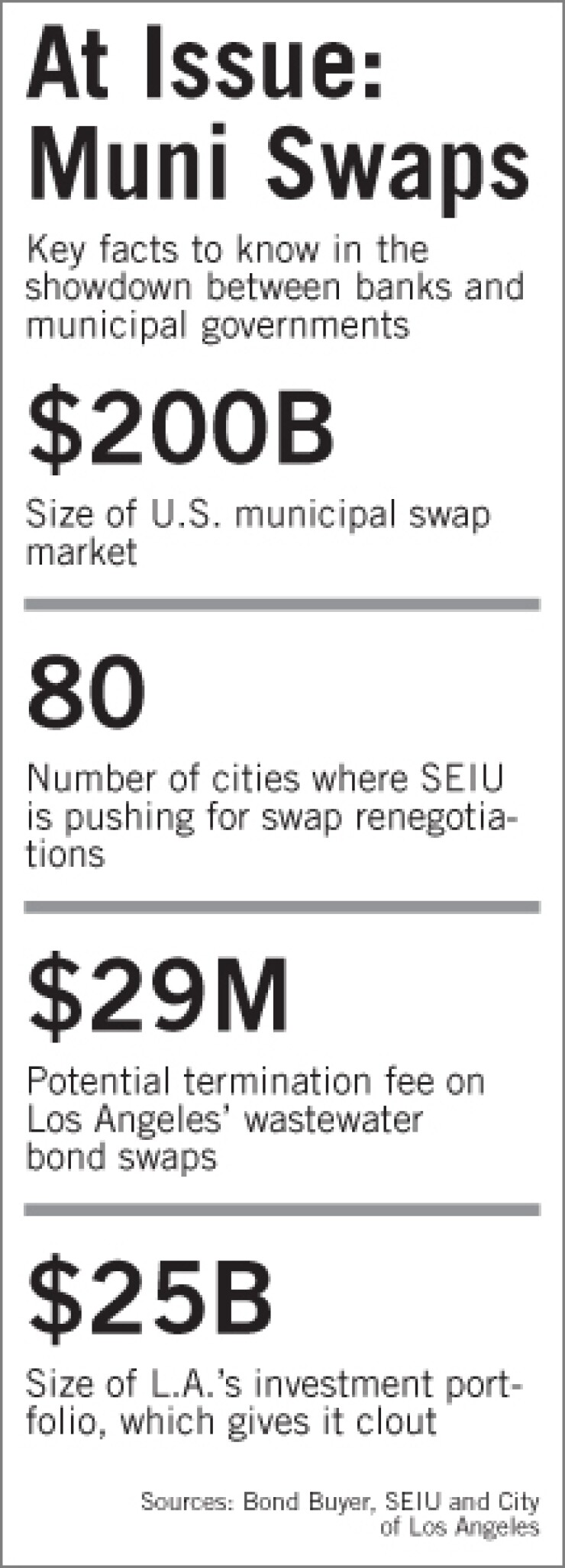

A municipal swaps version of The Huffington Post's "Move Your Money" campaign, the effort could harm banks' relationships with local governments and potentially force concessions on some of the more than $200 billion of municipal swaps outstanding, some industry observers said. More broadly, it underscores banks' weakened political standing, and the threat that poses to their day-to-day business.

"I'm not sure you really want to litigate the swap contract. Municipal finance is a tight community," said Jeffrey Cohen, an attorney for Patton Boggs who has worked for borrowers and issuers alike.

Though many big banks have exited the municipal swap business — both JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. largely shut down new issuance after a series of price-fixing scandals — the outstanding contracts are a tempting bone to pick for municipalities facing job cuts and ratings downgrades.

Distressed public entities have already won concessions on termination fees in Detroit and Jefferson County, Ala. Many believe healthier jurisdictions may already be quietly getting in on the game. If municipalities can issue debt at lower rates, "they're going to raise whatever defense they've got," Cohen said.

According to several industry observers, substantive grounds for demanding renegotiation are often reed-thin. By swapping variable-rate debt payments for a fixed-interest obligation, a local government bought protection from the risk of rising interest rates, while paying significantly less interest than it would on a comparable fixed-rate municipal bond.

In Los Angeles' case, that meant that the city entered into a 2006 deal to pay 3.4% a year on $317 million of debt to Bank of New York Mellon Corp. and Dexia SA, receiving the prevailing adjustable rate payment in return. For a couple of years, that was a good deal, producing several million dollars of savings a year. But when the Federal Reserve dropped interest rates to nearly zero during the financial crisis, the city's 3.4% payment started earning it 0.15% back. Terminating the agreements would require an immediate fee of $29 million.

In one sense, the change did not make any difference — the very reason the city had taken out the swap in the first place was that it did not want to gamble on interest rates, and its total payments on the bond-and-swap package remained steady. Construed in a different sense, however, the fallout from the financial crisis allows banks to buy municipal taxpayer dollars for fewer than 5 cents each at a time when Los Angeles was facing widespread cuts to city services.

That was how city Councilman Richard Alarcon saw it at a meeting late last month, where he called for city staff to demand that Dexia and Bank of New York Mellon "negotiate in good faith and give us back our money." It's not clear that everyone involved understood the purpose or mechanics of the deal — Natalie Brill, the city's debt management chief, was asked to explain it several times — but the subject was a crowd pleaser. Applause met Alarcon's more aggressive statements, and the audience audibly gasped when Brill said the swaps agreements would last until 2028.

Some experts were skeptical that any counterparty would ever tear up a swap contract, but justifying smaller concessions, however, might be easier. As Brill said regarding Los Angeles, "it can't hurt to try."

On Friday the council voted 12 to 0 to "attempt to renegotiate current swaps deals" as part of an ordinance allowing the city to stop doing business with banks that do not meet certain social responsibility criteria such as loan modification and community reinvestment.

The SEIU is urging other municipalities to take similar actions.

"Services are being cut so that the money can go to Wall Street, and 50% of that is going to pay wealthy individuals. That's just not acceptable anymore," said Stephen Lerner, head of the SEIU's financial reform project. While the SEIU has far broader concerns about the banking industry, it picked swaps because their "grotesque" mechanics make it easy to argue that public money is being given away, he said. Following Los Angeles, the SEIU said it has lined up political support for a similar push in Oakland beginning Tuesday, and that it's in the process of talking to political allies in another 80 cities.

Aiding such a campaign, Lerner said, is the public tarring the industry brought upon itself with the wide-ranging price-fixing scandal in late 2008. B of A and JPMorgan Chase abruptly stopped selling municipal swaps amid federal investigations then, and Matt Zames, then head of JPMorgan Chase's tax-exempt capital markets division, cited the reputational benefits the company would get from dropping the business.

"We actually think, in the medium term, we're going to be viewed as a leader," he told The Bond Buyer at the time.

Neither Bank of New York Mellon nor Dexia Local responded to requests for comment.

Not everyone agrees that municipalities have strong legal cases. One municipal swap adviser privately called efforts like Los Angeles' "unprecedented" and "ridiculous," and in a statement to American Banker the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association said political pressure to modify swaps would be misguided.

"Contracts bring certainty to parties involved in a transaction and to the larger financial markets," a spokesman wrote in an e-mail. "Having changes to contracts imposed by anyone, rather than those freely agreed to by parties involved in the transaction, undermines that core structure that market participants depend on."

In the end, the nature of the swap issuer's business may influence the entities' reaction to requests like Los Angeles', said Matt Fabian, managing director of Municipal Market Advisors. Institutions that do not generally participate in municipal debt issues or that have either sold or fully hedged their swap positions are unlikely to grant any concessions, he said. But for coast-to-coast U.S. banks that have deep roots in the municipal market, dealing with clients who are paying more than they would like on swaps but cannot afford termination fees is more delicate.

"It's been a balance for the counterparties, trying to look out for their issuer clients, while at the same time you've got contractual agreement. Most of this has been done quietly," he said.

That approach is backed by G. Allen Bass of Lewis & Munday, who helped Detroit negotiate with swap holders after a ratings downgrade last year that put the city at risk of having to make $400 million in termination payments to UBS and SBS Financial Products Co. The swap was partly guaranteed by Merrill Lynch. While there was some public posturing by both sides, Bass said, progress was made in calm meetings behind the scenes.

Though Bass declined to discuss specific negotiations with either bank, he said his experience supported the view that American institutions with reputations to protect in the muni market were far more accommodating than foreign counterparts who had largely exited the business. In the end, however, both sides agreed to drop the termination payment in exchange for an 80-basis-point increase in the city's swap payments, a far less valuable result for the banks.

"I'll put it this way — the counterparties had some decent arguments that a termination event had occurred," he said. "But after a while, they realized that if they pushed this, it was just going to drag on and on, and it was not going to be a profitable exercise."