Many economic cycles hence, historians looking back at the first years of the 21st century will count them among the most misguided or innovative periods in residential real estate lending. Or maybe they will simply number them among the industry's luckiest.

Credit quality is why. Over the past 18 months the mortgage industry has undergone a revolution in the way it lends and in the kind of loans it makes.

But a robust debate has sprung up as to whether this revolution has been a good thing, even as credit quality has risen to unprecedented highs.

In dozens of recent interviews with lenders, regulators, insurers, investors, analysts and other experts, American Banker found a high degree of concern about how well the risks of loans being written today are understood and the possibility of adverse consequences of varying degrees.

To be sure, it's no secret that analysts and economists have lately been looking for chinks in the mortgage industry's armor - and have found many. Real estate bubble talk has begun to bubble over. Much attention has been paid to the explosive growth of products like interest-only and negative-amortization loans that have enabled prices to keep rising.

But as industry players increasingly voice their own worries, they bring the debate to a new level. At the least, their insights suggest that a rollback of the revolution may be in the offing, though some executives quietly acknowledge that so far pressure to keep up with competitors has at times trumped their better judgment.

Many wonder when and how it will end, and who is pushing the envelope too far. "The big question is: Who are the originators taking the left-handed path" - where risks are taken blindly - "and who are the originators taking the right-handed path?" said Andy Pollock, the chief executive of National City Corp.'s nonprime mortgage unit, First Franklin Financial Corp.

"Only the future will tell" who has been disciplined, he said. "In a broad sense," he added, "2005 is setting the stage to be eerily parallel to 1998," when several big subprime lenders ignored loan quality in pursuit of volumes, sowing the seeds for their demise.

These days, not only lending classified as subprime is treacherous. "What you have is a much greater preponderance of high-risk loans than I've seen in any cycle in the past," said John M. Robbins, the chief executive of AmNet Mortgage Inc. "My guess is 50% of loans made today probably fall in a 'high-risk' category."

Like many, Mr. Robbins, a 33-year industry veteran, is not sure things will turn out so badly. Only if rates spike, the economy tanks, and home prices decline will the recent crop of loans "really get their full measure of testing," he said. "Then, we'll really find out what kind of problem we've created."

In a recent interview, Julie Williams, the acting comptroller of the currency, sounded worried that mortgage lending is headed in the wrong direction, saying banks must "recognize that there are some variables here for which we don't have experience."

"We would say that underwriting based simply on the best possible introductory scenario is incomplete," she said, and the OCC "has concern that it may be" used too often.

"I think we're at a stage in the cycle where it's appropriate and possible for banks to do the sort of prudent self-correction that they might need to do," she added, such as being more careful with risky products and keeping a close eye on their loan books.

Scott Albinson, a managing director at the Office of Thrift Supervision, said the regulator for savings institutions also sees a need to scrutinize how sensible they have been with new products. Because of thrifts' strong capital levels and reserves, and a variety of approaches and geographies, Mr. Albinson said, he does not worry about "systemic-type risks." But "from a supervisory standpoint, we are definitely concerned."

How much backpedaling is possible is an open question. Broad factors are at work, such as longer-term changes to lending tolerances and methods, little fear of credit risk in the capital markets, competition from new sources such as real estate investment trusts, and banks' increased focus on profits from already leveraged consumers.

COMPETITION HEATS UP

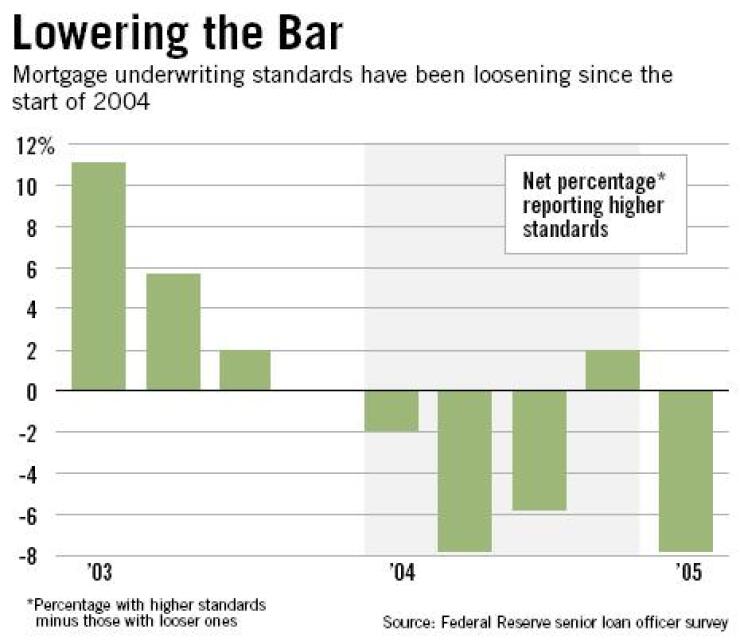

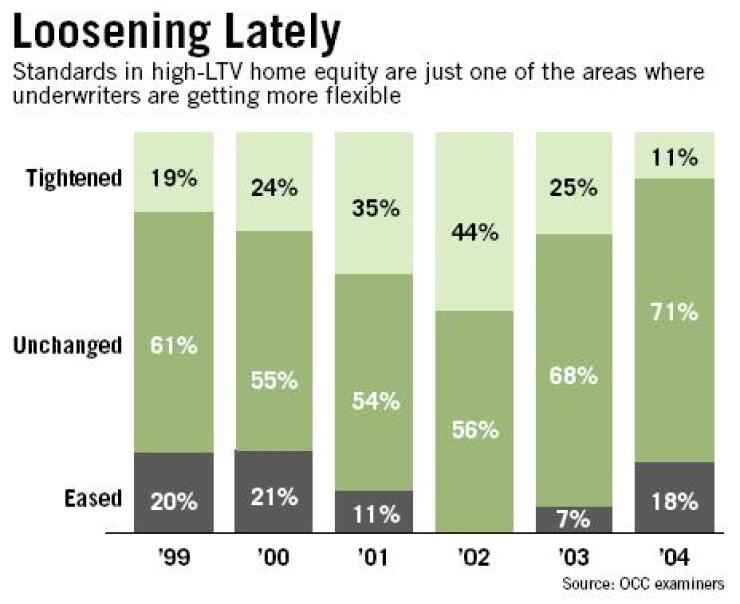

As is typical in the wake of a refinancing boom, underwriting standards have loosened as lenders, securitizers, and others attempted to maintain volumes. Once again, many formerly prime-focused lenders also have branched out into riskier loans with fatter margins, not all of them labeled "subprime."

Many lenders that chose not to originate riskier products, or to take things slowly in this area, lost business from brokers and borrowers, and then rushed to offer them. And to cut expenses and compete on speed and convenience, many lenders have made streamlining processes - often by reducing the vetting of supposedly low-risk loans - a priority.

Hard to see has been the extent of the changes in thresholds for granting loans and terms that were once considered niche products. Also dramatic has been widespread consumer and lender acceptance of mortgages with the potential for severe payment shocks or gradual escalation in monthly payments or debt burdens - often on top of risk factors like high debt-to-income and loan-to-value ratios or reduced documentation.

Hot products have included adjustable-rate mortgages, hybrid and interest-only variants, fixed-rate IOs, "option" ARMs that can bring negative amortization after the first month, floating-rate first-lien lines of credit, and first mortgages with floating-rate or shorter-term seconds behind them. By some estimates, ARMs now make up nearly half of all originations, and, as affordability issues often drive their use, many come with features that cut initial payments.

As in other forms of retail lending, mortgage underwriting standards have increasingly looked mostly at a borrower's ability to make payments in the near future, observers say. Being underemphasized, as Ms. Williams has noted, is a homeowner's ability to ultimately pay back the debt.

One sign is the large number of loans where - often without charging higher rates - lenders do not ask for, or thoroughly verify, a borrower's income. In doing so, they rely on things like a history of avoiding delinquencies, a good existing credit or asset situation, a small change from previous housing costs, or information from a preexisting relationship with their institution.

At times, of course, a high down payment is in the equation, but frequently the willingness to take a home equity loan can do the trick.

K. Terrence Wakefield, the president of Wakefield Co. LLC, a Milwaukee consulting firm, and industry veteran, cautioned, "the competitive frenzy to create products that ignore the fundamentals of lending people money" carries big risks.

"With the real estate valuations that have occurred plus the characteristics of some of these mortgage products, it creates a geometric increase in the probability of a problem," he said. If the chance of a housing bust "was 15% to 20% two years ago, I would say it's 60% to 70% today."

FEEDBACK LOOP

In a feedback loop, the recent rapid increases in home prices - a decade and a half since housing prices last stumbled significantly in several markets - have helped fuel the willingness to downgrade repayment capacity. Opportunities to take cash out of their homes or sell when confronted with trouble have helped borrowers, while appreciation also has helped lenders limit the severity of losses when foreclosures occur.

Similarly, loan performance data has been tainted by two decades of generally falling interest rates. The environment mostly kept ARMs from adjusting higher and often bailed out borrowers with refis for lower rates and equity extraction. Many models rely more on recent data, and none of the data can say what happens after such a long period of extremely low rates, experts note.

Refis and high housing turnover have also left a vast majority of outstanding mortgage debt unseasoned, one reason for mortgages' current pristine credit quality. It generally takes several years before peak periods of delinquencies and defaults. And because of the churn, many current loans have been underwritten in the new environment.

The rise of interest-only hybrid ARMs with shorter resets is considered especially troubling, because a borrower is much more likely to have moved or refinanced after seven years than three or five, and a payoff obviously removes the risk of payment shock. According to originators, consumers, and press accounts, many interest-only ARM borrowers count on the ability to get out of a loan before their payments increase.

No doubt lenders, investors, insurers and rating agencies have better tools than ever, particularly several years of loan-level data, an explosion of other information, and computing power to crunch it in sophisticated models.

To make up for the uncertainty of untested parameters, though, lenders, ratings agencies, and other interested parties have had to tweak models and build in blunt discounts to projections.

For example, they look at past short periods of rising rates to discern how a borrower will react to a sizable payment shock. They pretend that the loan-to-value ratio starts higher for interest-only loans. They discount the weight of debt-to-income ratios on stated-income loans (sometimes called "liars' loans") or increase the subordination or pricing for all such loans below a certain credit score.

"How do you deal with some of these newer risks?" asked Mark F. Milner, the chief risk officer at PMI Group Inc.'s U.S. mortgage insurance unit. "Where there isn't good data" it can be "kind of like doing a thought experiment - saying, 'If you were in this situation, how would you respond?' " to supplement other ways to predict performance.

Many players also incorporate broader views of local economic and housing market conditions. Additionally, many build in operational checks-and-balances on riskier loans, such as closer reviews of appraisal values or more sampling of their files for quality control.

LAYERED RISKS

In predicting how the newer risks will pan out, however, the layering of several unknowns can be a huge challenge.

You can try to guess how much worse interest-only loans will perform than fully amortizing ones, or how loans done with unverified incomes will compare to those with two months' paychecks and two years of tax stubs. Much harder is figuring out what having the two factors together will bring.

And where managing the risks involves subjective thinking, a data-driven process becomes more open to faulty assumptions, such as exactly how dire a worst-case scenario to assume. It can be especially hard to foresee the potential domino effects of things like the harm from bad loans made by other lenders to secondary-market liquidity or to a housing market.

As Angelo Mozilo, Countrywide Financial Corp.'s chairman and chief executive, has noted, a wave of foreclosures followed by fire sales can lower "the price of every one in that neighborhood."

In many cases, the granting of a loan is not based on the worst-case scenario for payment shock. Sometimes applicants qualify based only on the rates of increasingly competitive teaser periods. Underwriting can also loosen in subtler ways, such as by allowing any single credit bureau's score to be used, instead of the middle of the three.

That is not to say that various players have not been making changes this year, such as uncoupling ARM resets from the start of principal payments on interest-only loans, or lowering the amount of negative amortization allowed above a home's value. Often, though, lenders simply increase their pricing.

Also to be tested in coming years are the industry's enormous secular changes of the past decade.

Since the mid-1990s, automated underwriting and risk-based pricing have emboldened lenders to overlook some imperfections in a borrower's situation. FICO scores have emerged as a singularly important measure of credit risks.

Piggyback home equity products have replaced mortgage insurance on many high-leverage deals, eliminating another check to loosening guidelines and reducing the lender's protection. Often desktop or drive-by reviews - and sometimes computer models - have replaced, rather than supplemented, traditional appraisals.

Pushing government-sponsored enterprises and banks to increase homeownership by serving riskier parts of the market has been a public-policy priority. Also, in part because immigrants and minorities are thought to represent a rising percentage of new homebuyers, lenders have been seeking ways to serve such "emerging" markets. Such efforts almost by definition include using untested means, such as alternative credit histories.

William C. Wheaton, a professor of economics and the director of research at the MIT Center for Real Estate, said that the use of "very, very loose underwriting" to increase homeownership among population segments that "can get themselves into trouble in one of a hundred ways" would backfire.

"It doesn't take much more than, maybe even less than, a one standard deviation [economic] event to throw" historical trends on the types of borrowers being nudged into homeownership "out of whack," Mr. Wheaton said.

"It may be what we discover down the road is that the delinquency rate is 10% permanently, or 15% permanently," he added. "It's just not sustainable to have 70% of the country owning homes."

THE FOUR C'S

Helpful data on the extent of risky lending practices is hard to find, in part because the layering of risks on individual loans can be hard to see in aggregate snapshots.

Definitional issues abound: What exactly is "alternative-A"? While the term is frequently taken to mean high-credit borrowers with documentation issues, it depends on whom you ask. Is it still "prime"? Does the fact that a borrower's income was not verified due to comfort with other characteristics (and not her request) mean her income was not "stated"? Which 80% LTV loans have "silent seconds" behind them?

What is clear is that in many cases, lenders are not looking at all the textbook "four C's" (usually capital, capacity, collateral, and character) historically used to judge creditworthiness. And often, the bar for what is acceptable on any one of the four has fallen.

Willie Newman, an executive vice president at ABN Amro Mortgage Group Inc., said the fast, widespread adoption of new products and "the layering of different risk buckets that would have historically been isolated" made the current loosening more spectacular than in past cycles. His company was slow to embrace interest-only and stated-income loans before competition and an expanded data set pushed it to be more aggressive.

There's no doubt FICO scores can be powerful predictors, but experts said their use in mortgage lending has not weathered a true test. Technically, the underlying formulas are designed to predict the likelihood a borrower will repay a loan in the next two years, making the scores perhaps less-than-ideal for 30-year debt. And there have been vast changes in consumers' credit behavior in recent years, as they have tapped home equity to avoid falling too far behind on their unsecured debt, freeing up revolving lines and further burnishing their scores.

Even if you think FICO is enough and you still consider it reliable, what is considered a good credit score has fallen from generally around 720 - the median for Americans - to more like 680, or even lower. Some view 620 as still "prime." And interest-only and stated-income loans (and sometimes loans with both features) are increasingly being given to subprime borrowers.

Meanwhile, how much of borrowers' overall pretax earnings can go to servicing debt has risen from a traditional 36% cap, to 40%, 45%, or more, before becoming a factor requiring subprime pricing. Any limit on pretax earnings going to housing costs (capped at 28% a decade ago) is pretty much a thing of the past.

Even with the more forgiving ratios, many industry sources said brokers and loan officers appear to routinely push stated- income loans to qualify applicants for the debt levels they want. Some believe brokers and loan officers even know how to game the system to streamline income verification without classifying a loan as "stated-income."

At the same time, what is considered a high down payment has eased from 20% to 10% or even 5%. And banks' desire for home equity loans in their portfolios, and an expanded market for home-equity-backed securities, let lenders do more such loans in lieu of down payments or mortgage insurance.

Now, imagine adding a range of newer loan products to these already changing underwriting equations - some with the potential for higher payments in the future, even if rates don't rise. Those increasingly popular teaser rates on hybrid ARMs are not fully indexed.

The shock on interest-only loans includes the squashing of principal payments into a shorter time frame. Without a sale or refi, option ARMs eventually require new principal accrued from minimum payments to be repaid over shorter time frames, too. Widespread concerns about hard and soft fraud on things like appraisals only heighten the risks.

Despite the appearance of newness, many of the niche products that have vaulted into the spotlight also emerged in past cycles. Negative amortization and low-documentation loans led to credit, reputation, and legal problems for some lenders in the early-1990s housing busts. (Two examples: Citicorp, the Citigroup Inc. predecessor, and Dime Savings Bank of New York, now part of Washington Mutual Inc.)

One reason for the aggressive use of them now, some veterans warn, is that memories of those blow-ups have receded. Some top mortgage executives were not in the industry then; observers say it is hard to imagine that they are keeping history in mind, judging from the types of loans being made and talk of housing prices never declining.

Mr. Wakefield, a former executive of Prudential Home Mortgage Co., which Wells Fargo & Co.'s predecessor bought in 1996, remembers.

"You probably have no concept of what the world is like," he said, "when people are literally standing outside the doors of banks and mortgage companies with their house keys in hand, waiting for the doors to open, so they can enter and drop off their keys."