When it comes to dividends, struggling banking companies are operating under the law of gravity, and they likely will be for quite some time.

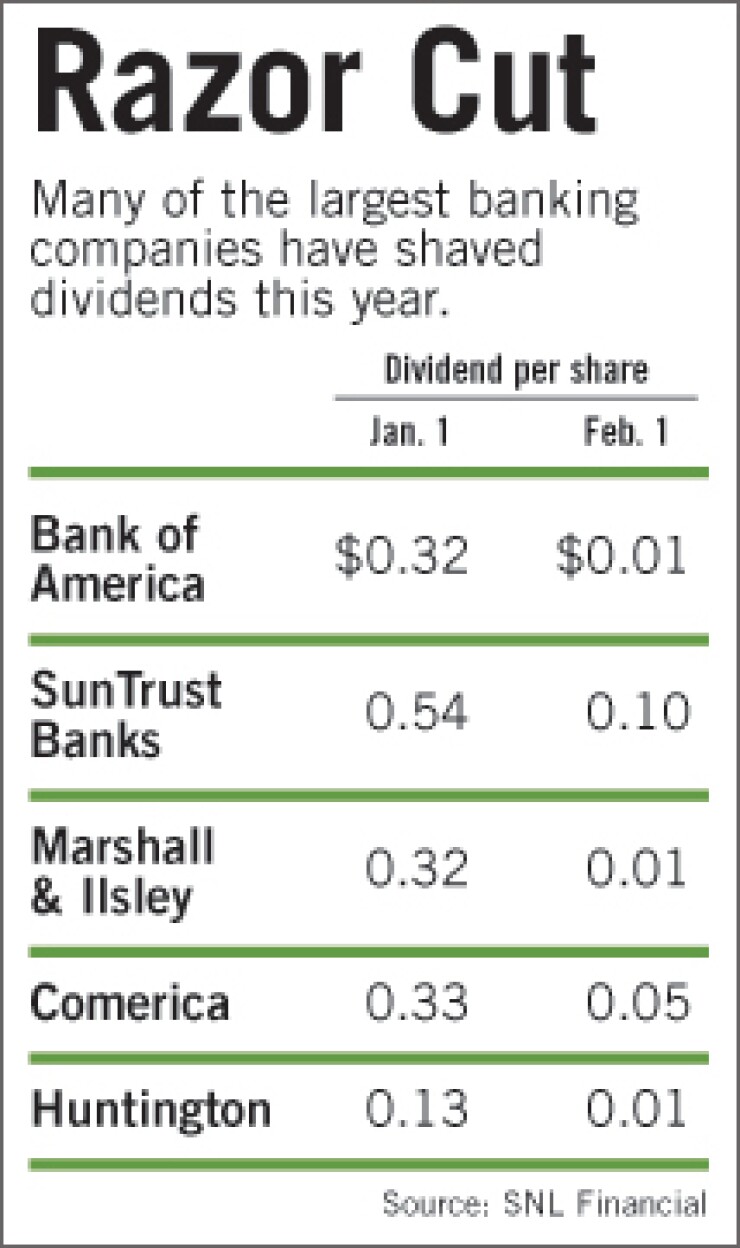

In the last 12 months roughly a third of the largest recipients of funds under the Treasury Department's Capital Purchase Program have sliced their dividend at least once or eliminated it altogether. More than half those companies took action in the past month.

Investors should not look for reversals anytime soon, analysts say. Many companies are wrestling with low capital levels, and under the capital program's term sheet, the Treasury's consent is required "for any increase in common dividends" through the third anniversary of the agency's investment.

Companies can get out from under the requirement by buying out the government, but that would involve raising capital independently, and most observers say that would be difficult for bankers, at least through this year.

"It could be a year, maybe even two years, before dividend levels return to normal," said David Hendler, a CreditSights Inc. analyst. "I think the regulators are encouraging capital conservation, because you don't know how much capital you are going to eventually eat through."

Analysts say the government's role in dividend cuts may be more implicit than explicit, but the results are the same.

Some companies may be cutting dividends of their own volition to husband capital, but Terry Maltese, the president of Sandler O'Neill Asset Management LLC, said his best guess is that troubled firms are "getting pressed by regulators to preserve capital in any way possible, and that would include cutting the dividend."

Gary Townsend, the chief executive at Hill-Townsend Capital LLC, said any pressure from regulators is subtle. "They aren't going to say straightforward to cut the dividend. … I don't think there would be any mandate, as long as there is reportable retained earnings."

There is a belief that the Treasury may let banking companies raise dividends to levels that existed before they received capital through the Troubled Asset Relief Program without approval. For example, a firm that cut its dividend in half, to 25 cents a share, after selling the government preferred stock might be allowed to go back to 50 cents without seeking the Treasury's blessing.

Mr. Maltese said it "isn't crystal clear" if bankers will have any leeway. Though they may be allowed to return to dividends that existed before Tarp infusions, he said there is a chance regulators will keep a tighter rein on such decisions.

"I don't think that any company that accepted Tarp funds would get an OK today to raise the dividend under those conditions," he said. "This issue will remain relevant for some time."

Mr. Hendler said that even if the government gave Tarp participants some latitude, bankers would be wary to reverse course on their dividend policies. "They will have to demonstrate an ability to grow retained earnings."

Many banking companies have tangible common equity ratios below 3%, he said, and they will need to consistently stay above 4% before feeling confident enough to raise the dividend.

Mr. Maltese said this year's earnings likely will not be robust enough to raise capital levels. "We expect earnings this year to remain depressed, and companies will want to wait for a couple of quarters of improvement before raising their dividends. I would be surprised if you saw a consistent stream of dividend raises before the middle of 2010."

Mr. Townsend also said that bankers have less cash to pay dividends, because they are also paying a quarterly 5% dividend on the preferred stock sold to the government. "That is taking away a bunch of earnings," extending the length of time before bankers may revisit dividends on common stock.

At the same time, many of the companies that have maintained or raised their dividend in the past year are getting peppered with questions from analysts about the payout's sustainability. For now, most are defending their ability to make their payments, and Mr. Townsend is giving them the benefit of the doubt.

"Companies that have not cut their dividends signal that they are very confident in their situation and their ability to manage through the current period," he said. "One has to assume that they understand their balance sheets much better than we can."

Those companies include Wells Fargo & Co., which faces questions about its 34-cent dividend after absorbing losses tied to the December purchase of Wachovia Corp. and reporting a $2.55 billion loss for the fourth quarter.

Howard Atkins, the San Francisco company's CFO, said during an interview after its earnings report, "Things can always change, but right now our capital is strong," and the management team is "growing the company" in a way that will internally generate capital.

At JPMorgan Chase & Co., where the dividend has been maintained at 38 cents a share, a spokesman referred to comments that James Dimon, the New York company's chairman and CEO, made Jan. 15 during its earnings conference call. He said the company's earnings power was enough to sustain the current dividend. "We never raised it to exorbitant numbers, so it isn't a yoke around our necks."

Analysts said the companies perhaps at the greatest disadvantage are those that cut dividends before Tarp came about, because their actions would be locked in regardless of how the term sheet is interpreted. First Horizon National Corp. in Memphis, Citizens Republic Bancorp Inc. in Flint, Mich. and Colonial BancGroup Inc. in Montgomery, Ala., suspended cash dividends before receiving approval for Tarp capital. (First Horizon did institute a stock dividend.)

Mr. Maltese said companies with deep dividend cuts are not going to be focused on boosting dividends with mere survival taking center stage. "If you have eliminated or cut the dividend down to a penny, … an inability to pay the dividend is the least of your worries."