-

Two top Obama administration officials said Tuesday that the GSEs would not be exempted from a pending proposal to help standardize mortgages sold into the secondary market.

March 15 -

Regulators must reject this transparent attempt by the megalenders to use rulemaking to enhance profit margins at the expense of consumers and independent mortgage lenders.

January 25 -

As regulators try to collaborate on new securitization rules, a fissure has emerged in bankers' own thinking on the subject.

December 2 -

Quite apart from financial losses, the massive foreclosures of the past few years pose another, long-term problem for the mortgage industry: fewer potential borrowers.

March 22

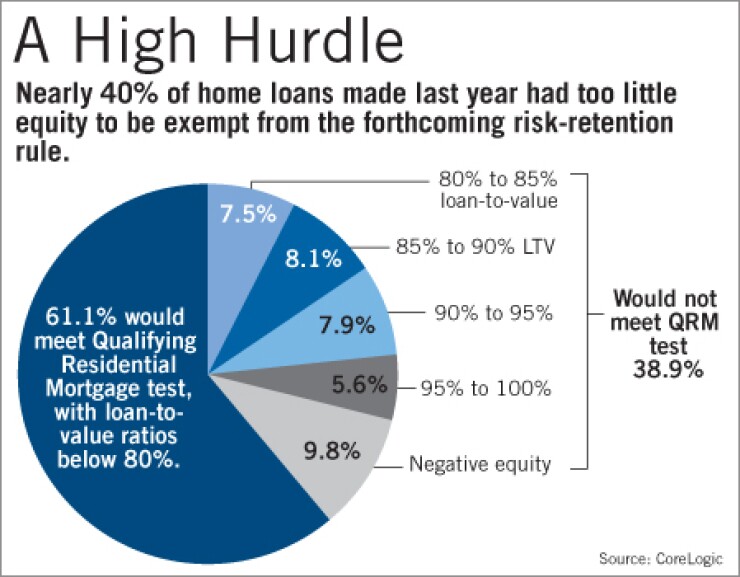

Forthcoming regulations could make conventional mortgages more expensive to the wide swath of homebuyers and owners who can't put 20% down, depressing originations and potentially undermining the housing recovery.

If 20% down becomes the standard for "qualifying residential mortgages," nearly half of all current homeowners with a mortgage, and 70% of first-time homebuyers would not make the cut, according to the data firm CoreLogic.

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, lenders will have to retain 5% of the credit risk of any non-QRM home loan they securitize. Therefore, whether or not lenders held such loans in their portfolios, they'd have to hold capital against them — a cost that's apt to be passed on, in the form of higher mortgage rates, to borrowers without 20% equity.

"The economics just don't work," said Cameron Findlay, chief economist at LendingTree, a unit of Tree.com Inc. He estimates that rates for low-down-payment loans could rise as much as 3 percentage points. "We think the housing market would be hurt through the endorsement of a mandatory down payment."

Six federal agencies are expected to issue a proposal next month defining QRMs as having

The rule could drive more borrowers to seek Federal Housing Administration loans, which still allow down payments as low as 3.5% and are exempt from the risk-retention rule. Such an influx would further increase the government's already-sizable involvement in the mortgage market.

"It does seem like it would put taxpayers on the dime for losses on those mortgages that go to FHA," said Ellen Schloemer, an executive vice president at the Center for Responsible Lending, a housing advocacy group.

But the FHA, whose market share has swelled in recent years as other low-down-payment products went away, may not welcome the additional business. David Stevens, the departing FHA commissioner, had said one of the agency's goals was to shrink its market share to let the private market fill the void.

"The concentration would significantly expand and move over to FHA at the same time that regulators are trying to reduce FHA's current 30% share of the market," Findlay said. "They are trying to figure out a way to adopt this change without crushing the market." He pointed out that the agency has already raised its annual premiums and that in September, higher loan limits will take effect that also will exclude some borrowers from getting FHA loans.

Housing economists are still crunching the numbers, but CoreLogic's preliminary estimates show that 2.7 million borrowers last year put down less than 20% to buy a house. The Santa Ana, Calif., data firm estimates that 10.8 million current borrowers with outstanding mortgages have loan-to-value ratios above 80%, while another 11 million homeowners owe more on their mortgage than their home is worth.

Sam Khater, CoreLogic's senior economist, said the typical household today has more debt than in the past, and asking borrowers to come up with additional cash would disproportionately affect the hardest-hit foreclosure states of Nevada, Arizona and Florida.

"Though higher down payments would make the market less risky, clearly it would price some borrowers out of the market," Khater said.

Though the proposal for stricter underwriting standards isn't even out yet, it has generated "a fair amount of furor" in the mortgage industry, Findlay said, creating some unlikely bedfellows. Housing advocates like the Center for Responsible Lending have sided with the National Association of Realtors and the National Association of Home Builders, claiming it now takes nearly 10 years for the average family to save for even a 10% down payment.

Mark Calabria, the director of financial regulation studies at the libertarian Cato Institute, said regulators are likely to find a compromise. One option being discussed is letting QRMs include loans with a 10% cash down payment and private mortgage insurance on another 10% of the purchase price, so a lender could securitize the loan without retaining a sliver of risk, he said. "There certainly is some sensitivity to not kicking everybody out of the market."

Some argue that even if it disqualified many consumers, making 20% down the standard is prudent. "So what if it excludes borrowers from the market?" said Rayman Mathoda, managing director of HausAngeles, a Los Angeles management consulting and real estate brokerage firm. "The point is the lender will have to retain 5% of the risk of excluded loans, which they should, so we have an alignment of incentives between loan originator (and usually also the servicer), loan investors and consumers."

James R. Bennison, senior vice president of strategy and capital markets at Genworth Financial Inc.'s mortgage insurance unit, said that if regulators wanted to prevent risky lending they could have done so without excluding so many borrowers in one fell swoop, by requiring that loans getting the QRM exemption be fully documented instead of setting a specific down-payment requirement.

"Low-down-payment lending isn't what drove the crisis. What drove the crisis was lousy underwriting," Bennison said.

Bennison and others also argue that regulators need to pay more mind to the overhang of shadow inventory — seriously delinquent mortgages and foreclosed homes that have not yet been put on the market — and the number of borrowers already excluded from the market. So far, 6 million homeowners have been foreclosed on in the past three years and another 3 million are headed to foreclosure, according to RealtyTrac. Most of those people are ineligible for new mortgages for as long as five years. "If you're going to exclude low down payments, then the conventional market will not help much in clearing the shadow inventory," Bennison said. "The QRM is going to drive the economics of who gets a mortgage and at what price."