-

Banks are providing less warehouse financing for collateralized loan obligations, so CLO managers have dusted off an old financing tool, delayed draws, to keep pace with demand.

July 8 -

Volatility in other credit markets is starting to spill over into leveraged loans, as more than a dozen companies have pulled refinancings and other deals in the primary loan market this month.

June 25 -

Banks bulked up on collateralized loan obligations again in the first quarter for risk management and other purposes. But new deposit insurance rules are expected to deter them from buying more.

June 17

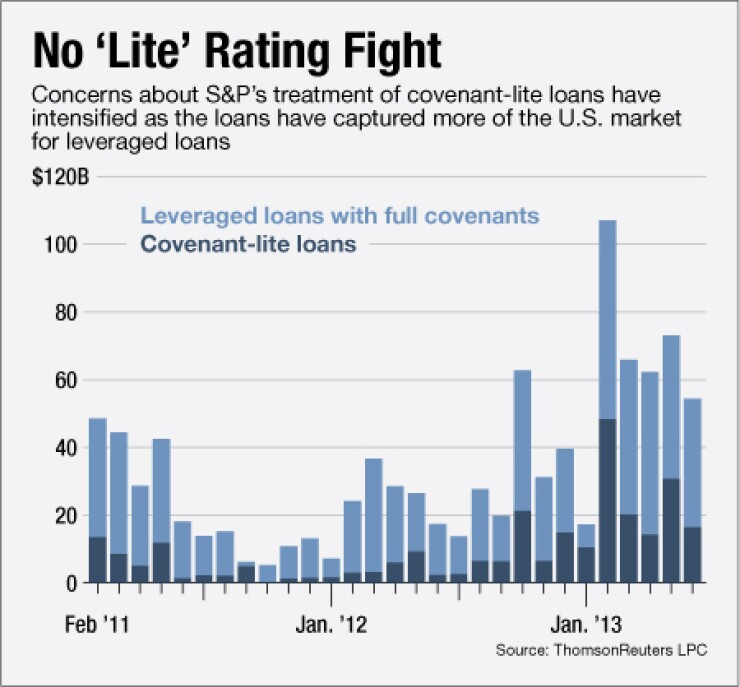

A shift in the leveraged-loan market has intensified grumbling among CLO managers about the way Standard & Poor's rates the senior tranches of these deals.

When S&P overhauled its rating methodology for collateralized loan obligations in 2009, it incorporated updated recovery ratings assumptions on loans in the collateral pool when calculating the cash available to pay interest and principal to senior noteholders. Recovery ratings indicate the amount S&P expects loan investors to receive if the issuer defaults.

The difficulty in this approach has to do with "covenant-lite loans," which the rating agency said usually have weaker recovery ratings and, as a result, get less recovery credit.

CLOs issue bonds and use the proceeds to purchase a portfolio of noninvestment-grade corporate loans. As the market has heated up,

In an April 5 report, S&P spoke about the dangers of rising issuance of covenant-lite loans. It said that its methodology actually captures the risk by using the same obligation-specific recovery ratings for both covenant-lite and full covenant loans.

Yet that puts covenant-lite loans at a greater disadvantage, and makes it harder for CLO managers to achieve triple-A ratings for portfolios with these types of loans. The rating agency declined to comment for this story.

Covenant-lite is a type of loan where funding is given with limited restrictions on the borrower's debt-service capabilities, including collateral, payment terms and level of income.

David Preston, a CLO analyst at Wells Fargo (WFC), flagged the issue in a June 27 report that discussed the impact of the test on CLO managers' selection of assets.

"CLO managers bring up the issue of recovery ratings a lot, and there has been increasing talk of the market going to a Moody's-only rating and not using S&P," Preston said in an interview.

In the report, Preston wrote, "while the CLO market does not appear to be bumping against covenant-lite limits, covenant-lite loans might be a limiting factor in a more indirect fashion," through the S&P recovery test.

Two recent CLOs carried a Moody's-only rating. One was the Ares Enhanced Loan Investment deal worth $542 million due to close on Wednesday. The other was the Telos Asset Management's Telos 2013-4 CLO this month worth $363 million, according to Asset Securitization Report, a sister publication of American Banker.

Part of the problem is that CLO managers don't necessarily agree with S&P's recovery ratings for loans. The ratings range between "1" and "6," with a "1" indicating the highest level expected for recoveries in a default scenario. For example, a recovery rating of "2" indicates that S&P expects investors would receive 65% of their principal investment in the event of a default; and a rating of "3" indicates an expected recovery rate of 30%.

Preston says actual recoveries have proven to be much higher: Between 2007 to 2012, recoveries on assets with a "3" rating averaged 75%, more than twice the 30% figure implied by that rating.

"S&P essentially designed the stresses to hit the triple-A harder, with higher defaults and lower recoveries, and they stress the recoveries differently to reach the desired ratings on a AAA CLO," Preston said.

In his report, the analyst acknowledged that this methodology may be appealing to CLO investors, since the conservative projections for loan recovery rates give senior note buyers more confidence that their bonds will continue to perform well during periods of extreme stress. The downside, according to Preston, is that CLO managers might start selecting loans to use as collateral based on S&P's rating methodology, rather than their own view of the credits.

Some CLO managers agree.

"Generally, S&P rated CLOs will be 5 points lower for the triple-A level weighted average recovery rate compared to Moody's," said Scott D'Orsi, a partner at Feingold O'Keeffe Capital who manages the firm's CLO business. "It has become more of a difficult hurdle. From an asset-recovery standpoint, what makes it a bit difficult is that sometimes it's hard to understand why a loan is assigned a recovery of "3," let's say, instead of a "1" or "2." Managers are forced to incorporate recovery ratings that might be inconsistent with their own credit analysis."

Managers often decide whether to seek a rating from a second agency. Market participants say that Asian and European investors, traditionally big buyers of the triple-A tranches of CLOs, are particularly interested in having both a Moody's and S&P rating on deals. Although these kinds of buyers have been less active in the market lately, there's a reluctance on the part of some CLO managers to use a single rating agency and risk reducing demand for the senior tranche in the secondary market.

"Whether a deal will be rated solely by S&P or solely by Moody's, or perhaps both, can depend on the sensitivity of the senior-notes investor group," D'Orsi said. "There may be AAA buyers that do not require two ratings, which in turn can have an impact on the collateral that is purchased. These nuances take place on a deal-by-deal basis."

Ultimately, the market might be geared toward either having Moody's-rated or S&P-rated deals, he said.

"Some collateral managers as well as CLO investors may migrate towards one agency over the other," D'Orsi said. "Moody's analysis tends to be more sensitive to corporate credit ratings while S&P's incorporates recovery ratings a bit more."

Other participants say they are resigned to S&P's use of loan recovery ratings, but would want more clarity about the way they are applied to CLO cash-flow analysis.

This article originally appeared on