Companies that put investors' money to best use ought to be the ones that investors value the most, but that premise appears to have fallen apart in banking.

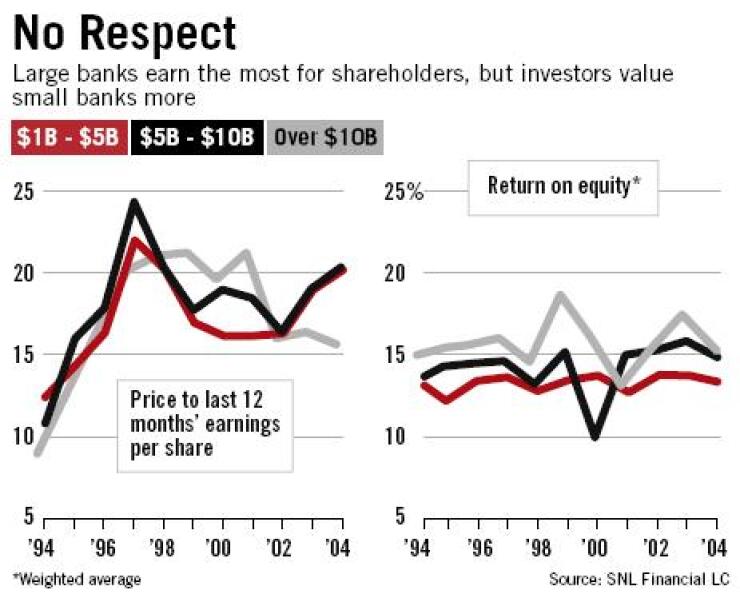

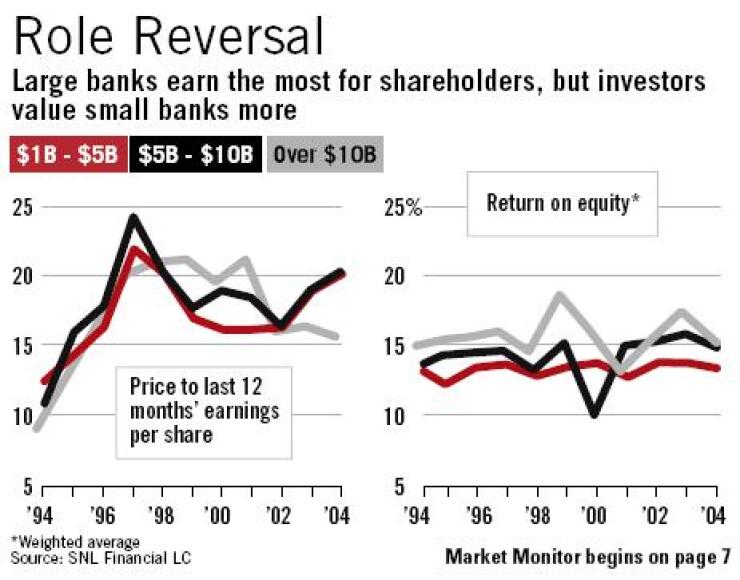

For much of the past decade strong profitability has been no guarantee of a strong stock price. Large-cap banking companies have consistently delivered the best returns on equity, but investors have nonetheless accorded small-cap and midcap banking companies higher price-to-earnings ratios.

The disparity isn't proof that investors are behaving irrationally. Return on equity is ultimately a window on a company's historical performance, while the price-to-earnings ratio is the best approximation of investors' hopes for a company's future. Apparently, investors aren't convinced that what a bank earned last year is the best indication of what it will be worth tomorrow.

The disparity between ROE and P/E is evidence that potential mergers and acquisitions and promises of faster growth are often more important to investors than performance.

"It's counterintuitive when you look at the P/Es," said Jack Micenko, an analyst at Susquehanna Financial Group. "A big part of the discrepancy between … small, mid-, and large-cap banks is M&A speculation, and that's why the small and midcap banks are valued more richly … regardless of profitability."

Banking companies with assets of more than $10 billion earned 15.2% on equity last year, according to a weighted average calculated by the Charlottesville, Va., research firm SNL Financial LC. Those with $1 billion to $5 billion earned 13.3%.

But the stocks tell a different story. At yearend banks with over $10 billion of assets traded at about 16 times their 2004 earnings; banks with between $1 billion and $5 billion traded at 20 times.

Assuming the right timing, the sale of an underperforming bank provides investors with a better pop - the instant gratification of a merger premium often proves irresistible.

Though they understand the allure of M&A speculation, many analysts say people would be better served by sticking to the fundamentals of financial performance when making investment decisions.

The P/E discount afflicting large banks is "something I've been talking to people about for the last six months, and I get blank stares, because they are so caught up in the moment and don't look at it from a historical perspective," Mr. Micenko said.

The St. Louis brokerage firm Stifel, Nicolaus & Co. runs unit investment trusts that buy bank stocks, but it does not specifically look for takeover candidates when picking equities for each trust.

"If we can pick 10 solid banks that we know are going to return 15% on equity and grow earnings 10% annually at a minimum, that's all we focus on," said Steve Covington, an analyst with Stifel Nicolaus. "We know just by looking at the numbers over the past 20 years that at least one in eight is going to sell - that's just icing on the cake.

"The important thing isn't picking the one in eight that sells. The important thing is picking the other seven companies that are just going to hit the ball down the fairway," he said. "That's how you outperform."

Investors do not favor small and midcap banks solely on merger speculation; they operate on the assumption that these banks can grow faster than large ones.

Mr. Covington said he expects the small-cap banks he covers to have earnings-per-share growth of 13% to 17%, while most large-caps are struggling to deliver 10%.

Chris Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners in Atlanta, said, "It's perceived as well as real that small banks are stealing market share from the big banks, and that is going to be a continual issue."

The large-caps also have a math problem. As they get larger, they need increasingly bigger increases in earnings and assets to deliver the same percentage return.

Even the interest rate environment and the economy favored small banks until the Federal Reserve started raising short-term rates. For most of the past few years small banks - which tend to rely on spread lending - were rewarded by a steep yield curve.

"It made a lot of sense to have a more traditional bank-like business mix," said Scott Siefers, an associate director of research at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP. Even during the commercial downturn, small and middle-market lending didn't suffer the hit that large-credit lending did, he said.

"You didn't see necessarily the same kind of commercial slowdown in the smaller names as the larger ones," Mr. Siefers said. "They didn't have the same sort of structural slowdown that you saw at the superregionals."

Investors preferring small banks reaped the rewards, as their financial performance improved compared with large banks', even though in many cases small banks did not perform as well as the big banks on an absolute basis.

"Buying a 12% ROE bank and having it improve to a 15% can generally give you a better return than buying a 20% bank that you expect to stay at 20% and produces 20%," said Jefferson Harralson, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. "A lot of investing is about finding inflection points, profitability, and growth."

The valuation disparity between big and small may soon disappear. Though the M&A market was strong in the first three quarters of last year, it cooled off in the fourth quarter and remains weak this year.

"Deal activity has really slowed down, and that is leaving the small caps' premium valuation vulnerable," Mr. Harralson said. "In the absence of deals, the premium does not seem sustainable."

Investors counting on deals may find themselves hoisted on their own petard, because bidding up the valuation of small banks has made mergers unaffordable. The higher the P/E discrepancy, the harder it becomes for a would-be buyer to make a transaction accretive.

"The larger names, the potential acquirers, are currently out of the market; they think pricing is too high," said Tom Monaco, an analyst at Moors & Cabot Inc.

The merger premium that pushes up the price of potential sellers has the opposite effect on buyers, Mr. Monaco said. Banks that have grown through mergers "are not going to get a premium multiple, because there is assumed to be some potential dilution associated with perceived deals."

Were investors to emphasize consistent financial performance, they would find that the structural factors that boost big-bank returns on equity are as present today as ever.

Large banks tend to be more leveraged and use relatively less capital than small banks do to support their balance sheet. A heavier reliance on traditional lending generally means a bigger capital cushion on the balance sheet.

"A lot of the large names are more diversified in terms of their business mix and might have some businesses that don't necessarily require a lot of capital but are profitable nonetheless," Mr. Siefers said.

"Those are generally higher-return businesses, as well: investment banking, investment management … even processing businesses," he said.

Mr. Micenko expects the disparity to shrink in 2005.

"You are bound to see … a compression of that differential, as the large banks in an improving economy may benefit from their exposure to capital markets and the small banks get hurt from the flattening yield curve."

That may mean it's time to get back to investing basics.

"Fundamentals are going to be more valuable to you over the long term when buying bank stocks," Mr. Harralson said. "You don't want to buy an underperforming bank stock just because you think it is going to sell because it can't grow earnings."