By changing one simple word, Wells Fargo has turned its back on decades of company messaging — and the move alone may have ripple effects across the industry.

Sometime last month, the embattled company decided to stop referring to its branches as "stores" (the Charlotte Observer was the

The move may have put a number of smaller peers in a tight spot: regional lenders such as Umpqua and TD Bank also use the term "stores" regularly, and may soon find it taboo.

Some observers dismissed the change as mere window-dressing by a company in crisis. Others called Wells' decision rash, arguing that ditching the term risks undercutting the company's broader approach to retail branching, which was until recently considered one of its key strengths.

But in another respect, the move may be long overdue, given how much the role of branches in banking has changed since the era of Stumpf's predecessor, Richard Kovacevich. Foot traffic has dwindled across the industry in recent years as customers turn to online and mobile channels. In the process, branches have become less effective places to pitch products to customers. While they may not disappear, as some fintechs gleefully predict, branches could evolve into something more like showrooms.

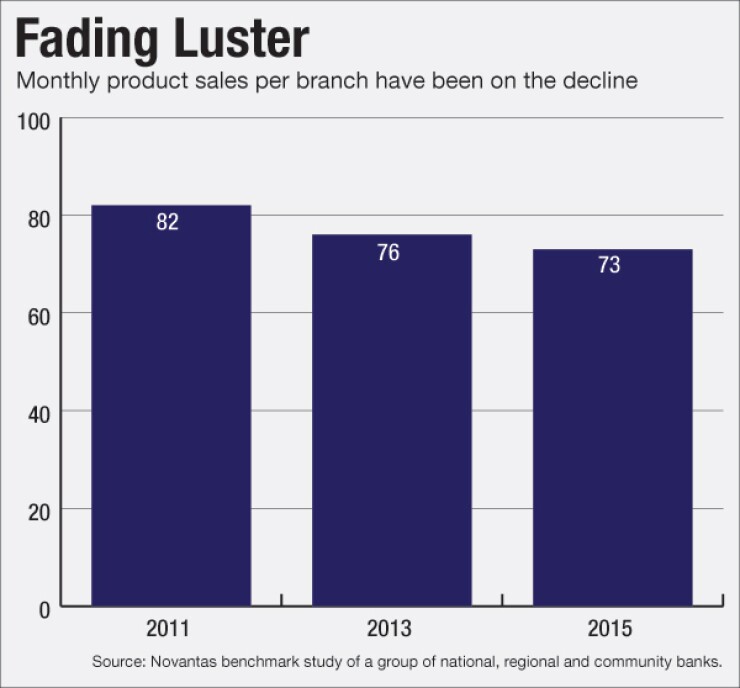

"Productivity has been falling, and it's been falling everywhere," said Kevin Travis, an executive vice president at the consulting firm Novantas. That is true whether it's measured in sales per branch or sales per full-time employee, he said.

No matter how you cut it, dropping the term "stores" is an extraordinary shift for Wells.

"What's remarkable is the degree that the company caved into pressure so quickly, as opposed to defending the spirit behind the approach," said Mike Mayo, an analyst with CLSA.

The official line from Wells Fargo is that it stopped saying "stores" to match the vernacular.

"Our customers tend to call our locations branches already — as places where people come to be with us and where we can serve their financial needs — and shifting to this terminology better reflects the way our customers think about us," said company spokeswoman Jennifer Langan.

Mayo argues that changing the nomenclature was a mistake. Wells crossed a line with its aggressive approach to cross-selling, but the word "store" also described positive aspects of the company's retail strategy, he said.

A store is a place that is "comfortable for customers," where they can access a range of products to meet their needs, Mayo said. "What's the matter with that?"

Ron Shevlin, director of research at Cornerstone Advisors, described Wells' move as "silly and meaningless," noting that problems at the company stemmed from misaligned sales incentives. Its broader approach to branching was not the issue, he said.

"Why is Wells changing its terminology? Because it's getting its wrist slapped — and appropriately — for abusing sales culture," Shevlin said. (Last month the bank agreed to pay $190 million, to settle charges that roughly 5,300 employees had created 1.5 million deposit accounts and 565,000 credit card accounts, without customers' consent, to meet sales goals and collect bonuses.)

The San Francisco institution has used the term "stores" for decades — internally and externally, on investor calls and

The term was widely adopted in the industry roughly two decades ago, when ATMs began to replace many of the transactional services originally offered by branches, according to Novantas' Travis. The industry underwent a "cultural shift" at the time, viewing their retail locations as places where products could be sold, he said.

In addition to Kovacevich, Vernon Hill, former CEO of the former Commerce Bank in New Jersey — which is now part of TD Bank — was praised for his retailing vision.

But that model is starting to look outdated.

"Across every branch network, understandably, there's less traffic, and fewer reasons to come in," Travis said.

"It's like a tanker. It's moving in a direction, and how far down the path of declining productivity does it have to get before we give up on it?"

A big question facing the industry is whether other companies will follow Wells in giving up on the word "store."

At least one executive has used the term in the weeks following the Sep. 8 settlement with regulators. Mike Pederson, head of U.S. banking at TD Bank, used the term "store" 12 times during a Sep. 13 presentation to investors.

Other bankers have used the term to talk about plans to boost activity in their branch networks.

"Branches aren't just places to take deposits and handle commercial customers. They're actual stores," said Todd Clossin, CEO of the $8.4 billion-asset WesBanco in Wheeling, W.Va., in a Sept. 7 presentation to investors.

During his presentation, Clossin outlined plans to measure year-over-year sales "much in the way that Target does."

A spokesman for WesBanco said Monday that the company uses a range of terms to refer to its branch network. TD Bank and Umpqua did not respond to requests for comment.

The change in Wells' lexicon comes as the company makes other changes to overhaul its troubled retail banking arm. Wells said last month that it would eliminate product sales goals for its branch employees, a week after it agreed to the $190 million settlement with regulators.

Whether Wells will make broader changes in its retail banking strategy remains to be seen. Some analysts, including Mayo, have called on the company to cut additional branches, in the wake of the scandal. During a call with investors last Friday, Tim Sloan, who took over as CEO last week, provided few details about the company's plan to turn itself around.

Even if bank branches defy their digital-age doomsayers, Wells Fargo's predicament has given bankers a different reason to be wary of a retailing mindset.

"Nobody is suggesting that the Gap is going to get in trouble for giving you a pair of khaki pants that make me look fat," Travis said. But in banking, retailing prowess has gone "from being a competitive advantage to being a large source of regulatory risk."

Kate Berry contributed to this story.