-

Two years after the federal government became a direct lender to students, the time might be right for small banks to start making private student loans. Still, there are plenty of potential legislative and regulatory headwinds.

April 2

A number of community banks are discovering that bulking up on student loans is easier said than done.

Banks are struggling to improve earnings, prompting many to expand the types of loans they make. Several smaller banks

Many of those banks are finding out why the larger banks back off; challenges abound in areas such as servicing and compliance.

"These are very risky loans," adds Andrew Gillen, research director at Education Sector, an independent think tank. Borrowers are often debt-ridden with federal loans when they apply for private loans.

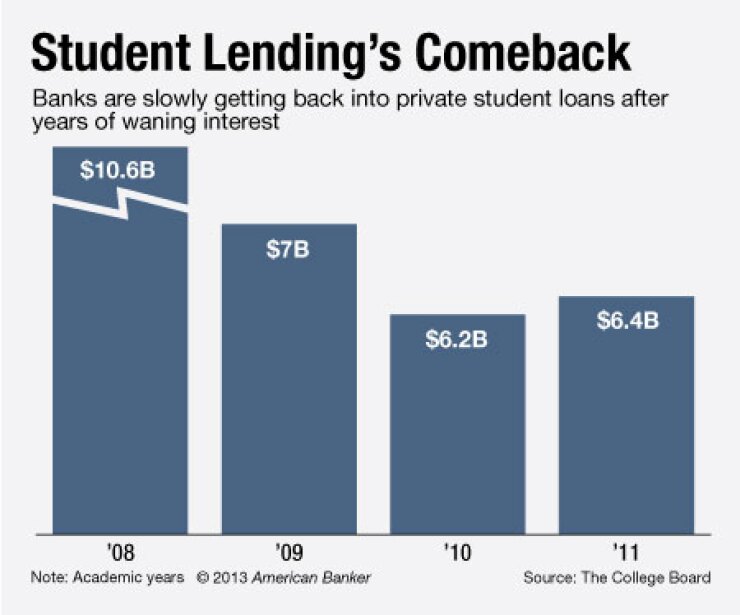

Private loans are down 72% from their peak in 2007-08, according to the College Board. Still, some banks are trying to make it work. Private loans rose 3% during the 2011-12 academic year compared to a year earlier, to $6.4 billion, according to the College Board.

Students once borrowed "whatever it took" to attend college, Gillen says. Today, students and their families are more concerned about the cost of college and are choosing cheaper options. More discretion, along with the loans' risky nature, has led to drastic declines, Gillen says.

The federal government's decision to stop guaranteeing private loans also contributed to the decline.

"The private loan market is an important supplementary source of funds" the College Board noted in a recent report. "But the loans generally have higher interest rates … and less favorable repayment provisions than federal loans."

Higher rates are enticing to some banks. Private student loans often have rates near 10%, compared to less than 7% for federal loans, Gillen says.

Student loans can also help banks diversify. Most community banks, which used to rely heavily on real estate loans, want to get away from CRE, says Steven Reider, president of Bancography. Some have

FMS Bank in Fort Morgan, Colo., began making private student loans a year ago to fill lending gaps, says John Sneed, the $133 million-asset bank's president and CEO. "First and foremost we try to serve the needs of customers in terms of C&I lending," he says. "We use student loans to get loan volume up."

FMS is willing to let student loans comprise up to 30% of total loans, based on demand, Sneed says. The bank uses iHELP, a program from Student Loan Finance that offers servicing, to address its inability to handle such tasks in-house.

Servicing is complicated, says Kevin Moehn, iHELP's program director. Cosigners are usually required, and the lender must work with colleges to certify enrollment and disbursements. Unlike other loans, repayment is typically delayed for years. Deferments and forbearances are common.

For those reasons, the number of banks using iHELP has more than doubled in the last year. "These loans are going to some of their best customers, who are usually upper middle income," Moehn adds.

Still, regulatory scrutiny looms, particularly from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The CFPB did not respond to requests for comment.

Rohit Chopra, the CFPB's student loan ombudsman, wrote in an October report that community banks could offer products that let younger borrowers refinance student loans at rates higher than the perceived repayment risk. This could help those borrowers move closer to homeownership.

Banks should expect more oversight because private student loans involve a potentially vulnerable population: young adults who often have scant little experience with finances, Moehn says. The CFPB has

"The regulatory burden is enormous," Sneed adds.

Compliance concerns prompted MidSouth Bancorp to wind down the student loan business it inherited after buying Peoples State Bank last year, says C.R. "Rusty" Cloutier, the Lafayette, La., company's president and CEO. After careful review, the $1.8 billion-asset company decided that the business was "just not profitable," he says.

"We looked at it hard," Cloutier says. "It's just not worth it to fight all of these government rules and regulations."

Default risk is another concern. In 2011, the unemployment rate for recent college graduates between 20 and 29 was 13.5%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. To account for this, many of the banks that work with iHELP take out insurance on their student loans, Moehn says.

Educating borrowers is important, says Terry Foster, CEO of MCS Bank in Lewistown, Pa., which hosts financial aid seminars. Delinquency rates on the $129 million-asset bank's student loans are lower than those for federal loans because of stricter underwriting, he says.

That being said, there are growing concerns that the increasing costs of higher education could create a new bubble. Outstanding student loans stand at $1.1 trillion, and the CFPB has been charged with finding ways to

"Student loan debt averages keep going up," Gillen says. "At some point, we're going to see this bubble default, but who knows when that will happen."