When John Ciulla took over as the chief executive of Webster Financial a little over a year ago, he promised shareholders that the change in leadership wouldn’t mean a change in strategy. Judging by the bank’s latest quarterly results, he’s delivered on that promise. But can he keep it up if economic conditions change or competition intensifies?

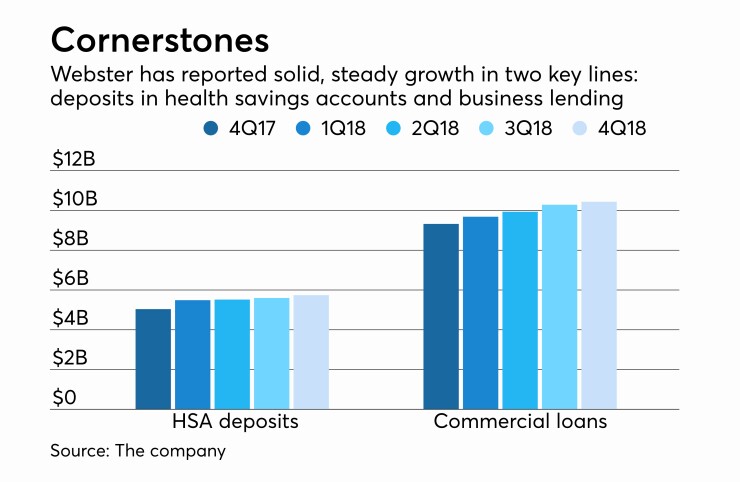

The Waterbury, Conn., bank posted fourth-quarter earnings of $96.7 million, buoyed in large part by growth in its health savings account unit and commercial loan book. But on a conference call Thursday with analysts, Ciulla fielded a question about credit risk and how the $27 billion-asset bank’s portfolio might perform in the next downturn.

It was a reasonable question, given Webster’s struggles after the 2008 financial crisis. At that time, the company saw its credit quality sour and its stock tank to $3 a share, and it took a $400 million government bailout, which it later repaid.

That period was a baptism of fire for Ciulla, who served as chief credit risk officer from 2008 to 2010. It made him ever mindful of credit risk, even when the economy is strong, he says.

“Dealing in difficult circumstances with the regulators and going through that made me a much better banker. And I am a much better CEO largely because of that experience,” Ciulla said in a recent interview.

Ciulla talked to American Banker about managing credit risk, how a bank Webster’s size has to be smart about technology investments, his appetite for dealmaking, and the cultural challenges of being the first non-founding-family member to run the bank since Harold Webster Smith started it 83 years ago. The following transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

There are a lot of concerns right now about when the economy will turn. In light of that, how do you manage credit concerns — and reassure your investors — at this point in the cycle?

JOHN CIULLA: When there’s a credit cycle, losses will go up. It’s a question of how well it’s managed and how well you do relative to your peers. I never promise we’ll be perfect, but if I think about where we were, as an organization, in terms of preparedness, portfolio management, understanding correlated risk in our portfolio, understanding the decisions we’re making, identifying the potential pockets of weakness, we are much better 10 years later as we potentially head into another cycle.

I think we’re still a little ways off, but we’re closer to the next one than we are the last one. The key is making sure you stick to your knitting, making sure you know what you don’t know, and making sure that toward the end of the cycle when your competitors are getting a little more aggressive and the nonbank lenders who are definitely in this space get more aggressive, that you don’t convince yourself you should try to keep up.

It’s sticking with your underwriting guidelines, sticking with your policies, and knowing how to take the risk you know how to take. ... We’ve been very deliberate. I really do think we are significantly better prepared going into this cycle, whenever it comes, than we were going into the last cycle.

Your home state of Connecticut has had some challenges with growth. Can you tell us a little bit about how geographic diversity has played a role in Webster's strategy?

We have a good market share here in Connecticut, so we have grown. We’ve grown our loans, and we’ve grown our deposits — albeit not at a rate that we would ultimately have liked to, compared to some of our other markets.

We’re high on Connecticut, and we do think we’re positively inclined. We see signs of positive momentum.

But before I became president, I ran the commercial bank. In the 12 years I was here before I became president, we expanded relatively aggressively outside the state of Connecticut. We have really robust commercial banking teams in Boston, Providence, White Plains, New York City, Philadelphia. We have commercial real estate and asset-based lending in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. We have asset-based lending in Atlanta, Chicago and Dallas. We have over the last dozen years had disproportionate commercial growth outside the state of Connecticut. We’ve been less reliant on the state than reliant on the major metro markets we’ve gone into. In hindsight, that was a very good strategy, given the fact that Connecticut has had its growth issues.

What’s your philosophy about technology? Do you buy, build or partner on new initiatives?

It probably is one of the most challenging strategic elements that a leader of a midsize bank can have, given the advantage that the large banks and the capital that the fintechs are seeing.

One of the things we did recently — and I use this word intentionally — we over-clubbed and acquired a new [chief information officer] in the middle of 2018. It was a key hire, one of my first executive key hires. Karen Higgins-Carter has experience at Bridgewater Associates, GE and JPMorgan Chase, among others. She’s got technology experience at a big company and big financial institution experience. She’s brought a very good perspective to us.

There is no one answer about whether we have a buy-versus-build strategy. I think what we’ve learned in the process is, we need to figure out what our customers expect from us, where we need to differentiate ourselves on technology versus where we can just be at market, and then figure out the most cost-effective and the most efficient strategy we’re going to take.

It’s been a very long time since Webster last engaged in M&A. What’s your appetite for dealmaking?

We’re very disciplined financially, so it’s not that there is an inherent lack of desire or willingness to look at transactions, but we’ve been able to generate above-market organic growth. We believe we’ve been able to create more shareholder value over time than we can in the current economics of partnering with another bank or buying another whole bank.

You’re less likely to see us engaged in M&A in the short term because we feel like we still have running room from an organic perspective in terms of investing in our businesses and growing at a faster than market rate.

What about the succession planning process was helpful for you?

It was really, really well planned, and the board was very much involved. Over multiple years, I took on increasing responsibility, always with an eye toward a natural progression towards the date that we ended up choosing.

The key was [his predecessor as CEO, James Smith] being completely committed to it. An organization with a really strong leader looks to that leader to see, is this something we really want? How committed is he to the new leader? How big a fan is he? So all the way through, Jim was really diligent and made a lot of decisions in light of the succession plan.

I became president in 2015, I took on more and more responsibility, and in that final year as president in 2017, I was basically a single direct report to Jim so functionally, the responsibility that I had in my first year as CEO was pretty similar to the functional responsibility I had in 2017. That made it really smooth.

You’re only the third CEO Webster Bank has ever had, and the first whose last name isn’t Smith. Were there cultural challenges associated with that?

Sure, to the extent you’re following an iconic leader who’s well respected in the industry, along with the fact that his dad [Harold] founded the bank, that does add a little bit of a “Can I fill his shoes?” But if there was any added pressure, it was offset by the fact that working for a bank with such a strong cultural foundation and having Jim be so committed to the succession made my job easier.

All of his deep knowledge and experience in the industry, through anecdotes or just sitting down and giving me advice, he was able to share those with me.

Maybe most importantly, he was always about, “You’re not going to be me. And you’re not me and you don’t want to be me. Because you have a lot of strengths that I don’t have, and I have strengths that you don’t have.” It was really valuable from a mentor perspective. He always encouraged me to be my own leader, have my own voice, and have my own management style. That really prepared me for the change of leadership. I had all this relevant knowledge, but no pressure to emulate who he was. I could be John Ciulla.