-

Mountains of bad assets have already been charged off, but mountains of underwater loans remain. However the meltdown plays out, most of the action is on bank balance sheets.

April 28 -

Enormous pools of home equity loans that in fact have little or no home equity standing behind them continue to inspire doubts about the nation's banking giants.

April 27

As banks labor to raise capital seawalls under orders from regulators, enormous pools of risky home equity loans continue to wash uneasily against their foundations.

Originally secured by real estate, hundreds of billions of dollars of this debt has been rendered uncollateralized by the crash in house prices. The balance sheets of the big four U.S. banks, which together hold about 40 percent of all home equity loans nationwide,

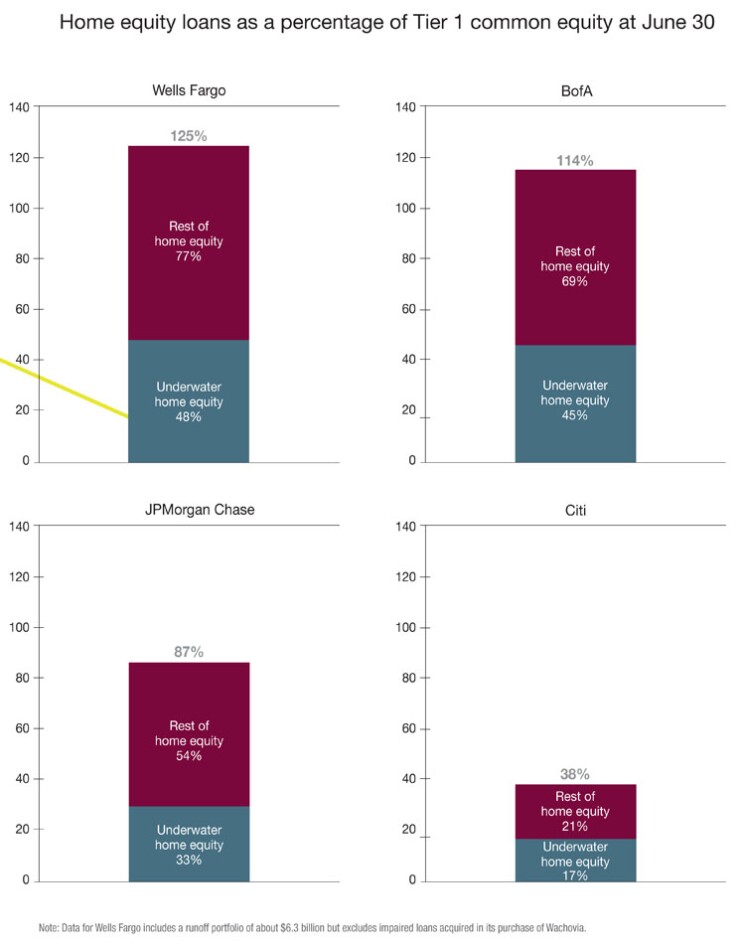

At Wells Fargo, underwater home equity loans—those for which combined mortgage balances exceed the value of the property—were equal to close to half of the company's Tier 1 common equity at June 30. (The entire home equity portfolio measured 125 percent of Tier 1 common.)

At Bank of America, underwater home equity loans were equal to 45 percent of Tier 1 common, including a $12.3 billion portfolio picked up in the company's purchase of Countrywide Financial. (Net of loss allowances, B of A carries those loans at about half of their unpaid principal balance.)

Citigroup has the smallest exposure of the four big banks, with underwater home equity loans in the U.S. totaling 17 percent of Tier 1 common. The company has a relatively small share of the home equity loan market, though it cranked up its production of closed-end junior liens for a time during the mortgage boom several years ago.

To be sure, the riptide of collapsing property values that stripped home loans of their collateral has weakened. After a comparatively mild second dip that began in the middle of last year, home prices have stabilized in recent months.

Delinquency rates also have subsided, and the banking sector already has charged off about $100 billion of home equity loans since 2008. (In total, home equity loans have declined by about a fifth since the end of 2007, to about $900 billion at June 30, according to Federal Reserve figures.)

Lenders assert that loss provisions are adequate in light of the payment behavior they have observed in the periods since the housing bust. But the portfolios have continued to draw regulatory scrutiny, and skeptics argue that borrowers who have defaulted on first mortgages are scrambling to stay current on second liens and preserve access to a line of credit, or are skating by on minimum payments.

B of A estimates that only about $5 billion, or 4 percent, of its home equity portfolio is current but subordinate to a delinquent first mortgage. Similarly, JPMorgan Chase estimates that about $4 billion, or 5 percent, is current but subordinate to a late or modified first mortgage, excluding the impaired loans it acquired when it bought Washington Mutual.

But home equity lines of credit are by definition revolving loans, and the vast majority of them still are within initial 10-year periods where borrowers are required to make only monthly interest payments.

B of A estimates that just $1.4 billion of its lines of credit have entered the phase where borrowers are required to pay down principal. And Wells Fargo estimates that 46 percent of its borrowers paid only the minimum due in June.