ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Expanding the health care center in Kewa Pueblo, a census-designated part of New Mexico home to the Native American tribe of the same name, is about more than caring for the tribe’s elders.

The planned hospice wing will allow them to remain home rather than seek such care in Albuquerque or Santa Fe, thereby helping them maintain the tribe’s heritage.

Preserving that heritage “is my biggest job,” said Joe Bird, the tribe’s warchief, gesturing to the plaza used for sacred rituals. "We’re very strong and we want to hang onto the way our ancestors intended for us to be, to keep the culture and keep the rules.”

But getting financing for the project is difficult. The tribe lacks a brick-and-mortar bank, and the main health care center was previously built with a complex array of federal grants and private loans. Officials are bracing for a similar process for the expansion.

Such efforts by Native American tribes to fund local projects have spurred calls for bank regulators to help direct financial resources to tribal lands through reform of the Community Reinvestment Act.

Some tribes and banks that serve Native American communities want regulators to establish designated CRA zones within tribal lands, meaning banks located anywhere in the U.S. would get CRA credit for investing in projects benefiting Native American areas.

“We don’t neatly fit into the same boxes that other constituents for the CRA change fit into,” said Dante Desiderio, executive director of the Native American Finance Officers Association, which advocates for tribal economies. “The modernization of the CRA can really change the capital flow into Indian country.”

Those focused on Native American financial services visited Kewa Pueblo last month along with Comptroller of the Currency Joseph Otting as part of a bus tour and forum, one of a

Possible changes include a new definition of a bank’s CRA assessment area to reduce emphasis on physical branches. The current definition is criticized for leaving out rural areas, sometimes referred to as “CRA deserts,” that are among the most in need of CRA investments but do not qualify for CRA credit.

Taking away tribes’ ‘invisibility’

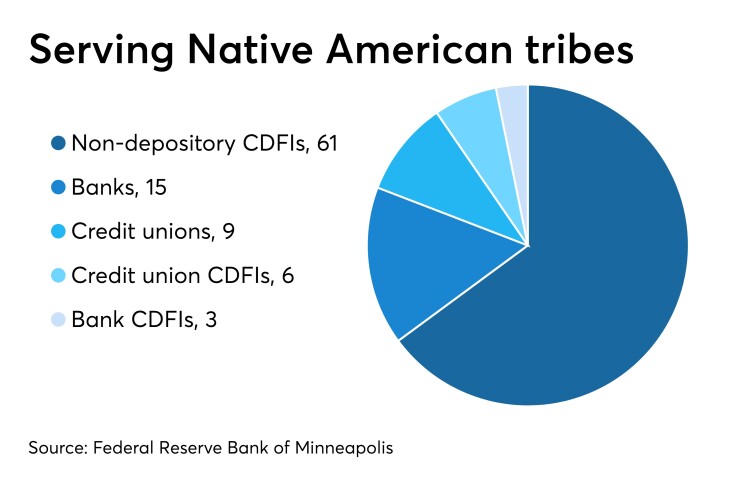

Ninety-four financial institutions in the U.S. — including banks, credit unions and community development financial institutions — primarily serve Native American communities, according to data by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. But those include banks that cater to tribal areas outside their CRA zone.

"In the more remote areas of … [New Mexico], we have made significant investments that have made even more significant advances to the employment [and] the housing and just the well-being of Native Americans, yet they do not qualify because they are out of our assessment area," said John Valentine, senior vice president of commercial banking and Native American financial services for the Bank of Albuquerque, a unit of the $39.7 billion-asset BOK Financial in Tulsa, Okla.

Valentine told Otting that “maybe” about half of the bank’s investments in Indian country were eligible for credit under the CRA.

CRA reform talks include the idea of allowing wider regional boundaries for bank assessment areas, perhaps after a bank meets requirements in a primary retail area. In March, Fed board Gov. Lael Brainard said another option would allow certain banks to have

But tribal advocates and bankers who do business on reservations want regulators to go even further by making Native American lands a designated assessment area under the CRA, potentially opening the door to any bank in the nation getting CRA credit for serving Indian Country.

"There's a huge unmet need for infrastructure in our tribal communities," said Lynn Trujillo, secretary of the New Mexico Department of Indian Affairs.

Lacey Horn, a former treasurer for Cherokee Nation, said designating tribal areas as special CRA assessment areas is “vitally important” and would take away the “invisibility” that Native Americans feel when they seek out banking services.

Yet there remain questions over how to define what Native American lands would qualify as a special CRA assessment area, partly because of the complicated governing structures that distinguish one tribe from the next.

Otting has led the charge among federal regulators in trying to advance CRA reform, at times even saying the OCC could issue new rules on its own if the agency cannot agree with the other regulators. But it was unclear if he supports going as far as designating Native American CRA zones.

Otting said the regulators’ approach may be to communicate to banks exactly what CRA targets they must hit in their primary grading zones before they can go outside those zones and serve more rural areas.

“If you could tell them, get to this level and now you’re ‘satisfactory,’ then they have the flexibility to go into other areas,” Otting said in an interview. “That’s really one of our goals.”

Proposal to spread CRA credit around

Beyond the issue of awarding CRA credit, Native American communities still

The average distance from the geographic center of a tribe’s reservation to the nearest bank branch was 12.2 miles, according to recent research from the University of Arizona’s Native Nations Institute. An earlier survey of tribes cited by the researchers found that 6% of residents had to travel at least 100 miles to the nearest bank.

Yet tribal groups see the CRA reform effort as a way to direct funds from banks all around the country to Native American communities.

For banks that lack expertise to navigate what can be complicated land and government laws among the separate tribes, one idea proposed to the OCC would allow big banks in other markets to receive CRA credit for moving cash into smaller community or tribal-owned banks that have been financing projects on reservations.

There is also a push to give banks CRA credit for providing funds to or partnering on lending with Native American-owned CDFIs, or even give banks credit for referring small-business loan applications from Native Americans to a tribal-owned CDFI.

Jackson Brossy, a member of the Navajo Nation and executive director for the Native CDFI Network, said at least one tribal-owned organization in rural Montana has been forced to set up like a payday lender because there was no bank presence nearby.

The CDFI does manage to charge only a fraction of the interest rates more common to payday lenders, Brossy said, but more needs to be done to encourage banks to invest in such ventures to keep loans affordable.

“We support modernizing the CRA so that we can address a lot of the challenges we’ve seen here,” Brossy said.

‘Well-kept secret’

On the Aug. 28 bus tour, attendees observed tribal lands’ critical need for development to combat housing shortages and aging infrastructure.

Nearly 24,000 miles of the roads — about 83% — governed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs system are considered in “unacceptable” condition, according to the agency’s fiscal 2012 study. A Government Accountability Office report in 2017 cited problems with the amount of data available on tribal roads.

The bus carrying the OCC’s tour had to turn back from one dirt road connecting two Pueblo tribes because it was too difficult to cross.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development under the Obama administration estimated tribes needed roughly 68,000 new housing units to alleviate overcrowding and replace homes that had fallen into disrepair.

Some homes still in use at Kewa Pueblo were built centuries ago. At nearby San Felipe Pueblo, there had been as many as 11 members packed into one-bedroom homes before the tribe started planning a massive new development on the outskirts of its territory.

Thomas Ogaard, CEO of the $160 million-asset Native American Bank in Denver, which is a CDFI, said economic development projects in Indian Country to address housing shortages and infrastructure problems have been a good business for banks like his, but that more firms should take part.

“It’s a well-kept secret,” Ogaard said.

Isaac Perez, executive director for the San Felipe Pueblo housing authority, said even though projects on tribal lands receive significant subsidies from the U.S. government, he has had to beg banks in the past to help fund development.

“We couldn’t get a bank to touch it,” Perez said.

Ultimately, the tribe was able to obtain a roughly $2.5 million construction loan from Bank of America. Not only is such financing guaranteed up to 95% by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but the San Felipe Pueblo was able to pay down the loan with annual allotments of $500,000 in assistance from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The BofA loan essentially allowed the tribe to get five of the HUD allotments upfront to start work on the project immediately. Newly built homes now wind through streets complete with a playground and cul-de-sac overlooking the sun-painted Sandia mountain range.

Otting ‘fairly confident’ about joint CRA proposal

Otting said the three bank regulatory agencies are still working to form a consensus on a CRA plan and that he is “fairly confident” they will issue a proposal jointly. He said he was encouraged by the feedback given by the Native American groups during the forum in New Mexico.

“A lot of people told me that I needed my head examined for going down this path” of seeking to reform CRA, Otting said.

He added, “If every nonprofit, every civil rights organization, every local politician knew exactly what qualified, where it qualified and how it was going to be measured” for CRA credit, it would make their relationships with banks better.”